The country has to set short-term pain against the long-term costs of the trade concessions sought by the USA, and think creatively

In the second week of August, India entered a dramatically different world. Citing its import of Russian oil, US president Donald Trump imposed an additional 25% tariff on the country, effectively boosting the tariff on Indian exports to the USA by 50%.

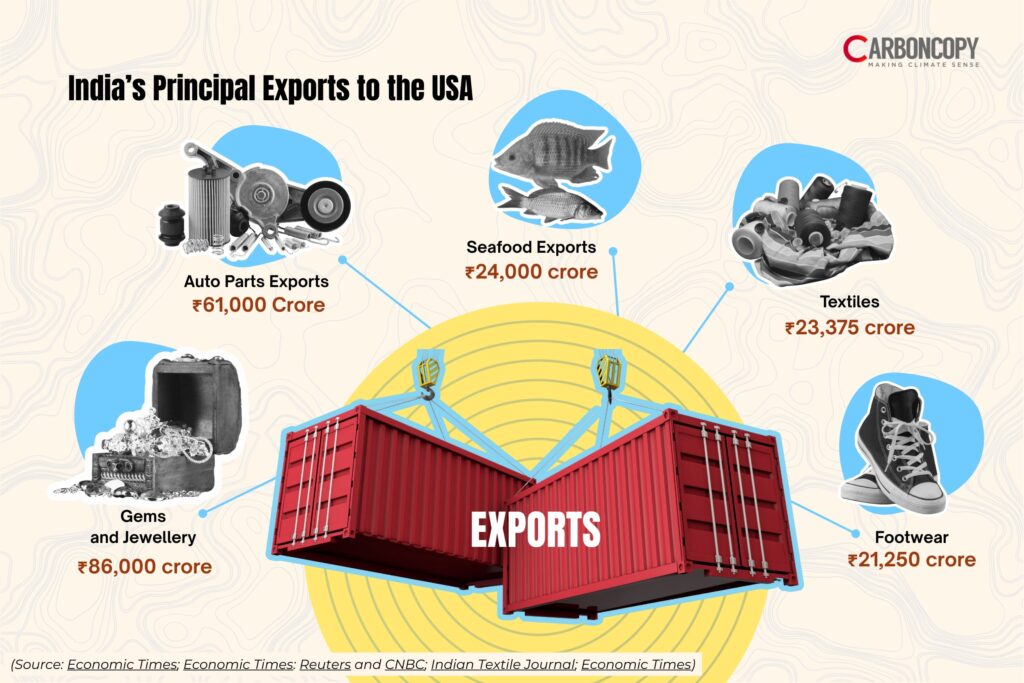

His decision cut off Indian exporters in labour-intensive sectors such as textiles, seafood and footwear and high-value sectors like gems, jewellery and auto-components from the world’s largest consumer market and left others like pharma and IT services wondering if they would be next.

It also undid several foundational assumptions underpinning India’s foreign policy. The first of these was the claim that Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Trump were close friends— and that their friendship would boost bilateral relations between the two countries. With the tariffs, however, the US-India relationship has slipped back several decades. “Suspicion between the two countries will get more entrenched after this,” said an investment banker working with a global FII (Foreign Institutional Investor).

Also in trouble are India’s efforts to position itself as a bulwark against China. “Geopolitically, we were in a sweet spot — as an alternative to China — which was supposed to push up our growth rate,” said the investment banker on the condition of anonymity. “That stands dented now. At this time, there is no panic, but FIIs are watching this very closely.”

Given such radical reconfigurations, India has been awash in opinions all of last week. Is Trump bluffing? Should the country seek detente with him? Or should it absorb these losses and boost trade elsewhere?

A time of turmoil

Trump has left a 21-day window before the additional 25% tariff comes into effect, creating speculation that these tariffs are no more than a negotiation tactic. This question, however, is less significant than it seems. For one, Trump might well be serious about these sanctions. “From what I know, the deal was nearly done from both sides,” the investment banker quoted above told CarbonCopy. “I think India’s rejection of his claims about brokering peace after Operation Sindoor rankled him.”

The other reason for the question’s relative insignificance is that even the 25% tariff is a body blow. With countries like Vietnam, South Korea, Taiwan, Indonesia and Bangladesh getting tariffs between 15% and 20%, almost all Indian exports to the USA will become unviable.

The costs extend from widespread job losses to an economic hit. Given the US was India’s top export market — accounting for 18% of the country’s (goods/merchandise) exports in 2023-24 and 2.2% of its GDP — even a 25% tariff could lower India’s GDP by 0.2-0.4%.

“We will survive, of course,” said the investment banker. “And yet, if 6% growth becomes 5.5% growth for some time, it is not good news.”

Should India offer trade concessions and resolve the issue?

With a clutch of other trading partners — like Indonesia, Japan and the EU — Trump dropped tariffs after the countries agreed to buy US goods. Indonesia’s tariff, for instance, fell from 32% to 19% after it agreed to buy $15 billion in US Energy, $4.5 billion in American agricultural products, and 50 Boeing Jets, many of them 777s. It also extended zero tariffs to US goods. As Trump told reporters after the deal:“For the first time ever, America’s ranchers, farmers, and fishermen will have complete and total access to the Indonesian market.”

With other trading partners, too, Trump has followed this template. The EU has agreed to buy energy and weapons. Trump also swung zero tariffs for US exports to Vietnam, while imposing 40% tariffs on goods transhipped through the country — a curb on Chinese exporters, mainly.

Should India follow suit? The country’s total exports (goods and services) to the USA stood at $86.51 billion (₹735,335 crore) in 2024-25, roughly a tenth of total exports ($824.9 billion, or ₹6,911,025 crore) that year. Of this ₹735,335 crore, according to India’s finance ministry, about 55% will be affected by US tariffs.

The immediate pain inflicted on these exporters, however, has to be measured against the longer-term costs of signing deals like the one Indonesia did.

In defence, Trump wanted to sell F35s to India. “The US wants us to buy 30-40 planes from them saying that is our trade deficit with them,” a veteran defence analyst had told this reporter earlier this year. “But we cannot take the F35. We already have the MIG, the Sukhoi, the Rafale and the Jaguar. We cannot add a fifth platform.”

Even in energy, questions about utility rear their head. As CarbonCopy has written earlier, imported gas is uncompetitive against the fuels it seeks to replace. Costlier to extract, shale gas is even more uncompetitive.

Take Tellurian. Between 2019 and 2023, the now-shuttered US shale gas manufacturer made multiple attempts — it even sponsored Howdy Modi — to sell 200 million tonnes of shale gas over 40 years to India. Even ignoring the $7.5 billion Tellurian sought as an investment from Indian PSU Petronet LNG, the deal worked out to a total payment of $62 billion over 40 years. At current prices, that would have translated to a net outflow of ₹527,000 crore. The deal, additionally, priced Tellurian’s gas at $6/MMBTU when spot prices were at $2/MMBTU — and the world was seeing a glut in LNG export terminals, raising questions on whether India should pick up equity in one.

Tellurian’s not an exception. India has also been forced to renegotiate its gas supply contracts with US shale gas manufacturers like Cheniere and Dominion. “The domestic appetite for expensive LNG is zero,” a retired Petroleum secretary told CarbonCopy. “For what we need, Qatar is cheaper.”

Look beyond weapons and energy — and the costs get larger yet. In agriculture, the US wants low tariffs on corn, soybeans, apples, cotton, almonds and ethanol plus market access for US’ genetically modified maize, soy, canola and cotton into India. Given that US farmers enjoy higher economies of scale — the average landholding in the US is 187 hectares; in India, 1.08 hectares — and greater state support, Indian farmers will struggle to compete with them. Accepting these demands, ergo, translates into both deepened precarity for Indians living off farming and allied activities — estimated at 54.6% of India’s total workforce— and the loss of food sovereignty.

And then, there is pharma. “It’s likely Trump will want the same concessions as the UK over pharma,” economist Jayati Ghosh told CarbonCopy, alluding to India’s recent FTA with the UK which promotes voluntary licenses (where a pharma company defines the terms under which a generic version of a patented medicine can enter the market from alternate suppliers, undermining access to patents) over compulsory ones (where governments can authorise production even without the patent holder’s consent).

It’s a gigantic concession. “Particularly in contexts such as the drug-resistant tuberculosis (DR-TB) public health emergency or the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, the decision to enable manufacture and sale of more affordable versions of urgently needed medicines must not be left to voluntary, “business as usual” commercial practices,” Medicins Sans Frontieres has said.

The litany of costs run deeper yet. In its deal with the USA, Indonesia will also remove all content requirements for US-made goods and accept American vehicle-safety and emissions standards. It must also recognize Food and Drug Administration approvals for medical devices and pharmaceuticals, exempt US food and agricultural imports from local licensing regimes, and accept US certifications for meat, dairy, and poultry products. In addition, the country, as Ghosh wrote, “has also agreed to eliminate tariffs on intangible goods and support a global moratorium on digital customs duties – issues that remain highly contested within the World Trade Organization”.

That is the calculus of this moment. Trump is using tariffs not just to boost US manufacturers’ access to foreign markets and to sell military hardware, he is also forcing other countries into trade agreements which, as with colonialism and neo-colonialism, are extractive (like the Ukraine critical minerals deal) or impinge on citizens’ wellbeing (as with the farm deals).

Trump has weaponized tariffs not just to extract trade concessions but also to bind other countries (including India) more closely to U.S. strategic and security interests, including by pressing them to boost defense spending and purchase more US weapons.https://t.co/TQ7UfZ4tn0

— Dr. Brahma Chellaney (@Chellaney) August 9, 2025

In the days after Trump announced his punitive tariffs, Modi said he wouldn’t compromise on farmers’ interest. And yet, as Ghosh told CarbonCopy, “The farmers are just the baseline. We cannot yield anywhere else either.”

This is one (big) reason why India shouldn’t rush to the negotiating table. There are yet others. “The 50% tariff comes with exemptions,” she said. “Apple already has one. As tariffs start to bite, American companies will lobby for relaxations.” It’s also possible that, as the USA slips into a slowdown — Wal-Mart has already begun raising prices — Trump will weaken after the US midterm polls in November 2026. Or he might just change his mind.

What India should do instead

India has to pick its cues from not Indonesia, but Mexico and Brazil. After getting slapped with high tariffs, Mexico and Brazil (50%) responded by seeking alternative trading partners. Countries in the Caribbean and Africa are doing the same. “This is now a multipolar world,” said Ghosh. “We have to hedge. We cannot be excessively reliant on any one partner. We have to make new friends and look for new openings.”

For decades now, India has been exporting 100cc motorcycles, cheap medicines (like Cipla) and buses to developing countries. “We should take the hit and look at other options,” she said. “We should become a manufacturing base for the developing world. The costs of doing anything else are too high.”

Can the country compete with China in those markets? In the days after Trump’s second tariff broadside, Modi told Indians to buy locally manufactured goods. For this to work, however, India has to tackle widening precarity. “If we boosted India’s median income by 5%, we would have a much larger domestic market,” said Ghosh. A large domestic market, she said, will also make the country’s exports more competitive. “China used its domestic market to create scale for its manufacturers,” she said. “Which is why we need urban employment schemes on the lines of MGNREGA [Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, 2005].” The country also needs to revitalise its Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) — and use them to drive growth. It also needs to start investing afresh in R&D.

The elephant in this room is China. India urgently needs to decarbonise and most of those technologies are owned by China. The country is also the biggest supplier of bulk drugs to India’s pharma sector. India-China relations, however, are rocky right now. China is not just helping Pakistan, it’s also cutting off India’s access to technology.

Endgame

Put it all together and it’s clear that India needs a fairly fundamental reset. Instead of seeking short-term relief at the cost of longer-term pain, it has to redo its relationship with the BRICS nations and the Global South into something more constructive, as opposed to allying with Israel and the USA to sell weapons to developing countries.

On energy, it has to mend bridges with China and double down on oil and gas purchases from past suppliers. “We will probably swing back to the Middle East countries,” said the former petroleum secretary. “The government has said it will let oil companies take these calls — which is then a function of price.”

What complicates this picture is the increasing subservience of foreign policy to domestic politics. “The relationship between Trump and Modi is over,” said the former petroleum secretary. “The QUAD [Quadrilateral Security Dialogue] is over as well. We have to mend relations with China. But domestic politics has its own compulsions.”

At this time, it’s not clear what India is thinking. In the weeks before Trump’s tariff shock, India’s oil companies were in talks with US shale gas exporters. In the days that followed, officials were weighing trade concessions they could offer the USA. In tandem, however, the country paused plans to buy arms from the USA.

Hardwired into this moment is that old Chinese adage about each crisis also being an opportunity. India has a chance to reimagine its trade relationships and its place in a reorganising world.

About The Author

You may also like

What COP30 reveals about the next phase of multilateralism

The G20 Has Outrun COP on Climate Finance

As COP30 rolls out a tropical forest fund, how are India’s natural forests doing?

COP30 Kicks Off With Hard Talks on Money, Adaptation and Global South Leadership

Can multilateralism still deliver at COP30?