This is an abridged version of the interview first published in Chinese in Initium Media on April 7, 2025. The full interview in English can be found here in the substack Crunch Times.

Editor’s Note

This interview with Tasneem Essop, Executive Director of Climate Action Network (CAN) International, was conducted by Chinese journalist JIANG Yifan in late January 2025, just after COP29 ended in Baku. As countries prepare for COP30 in Belém, Brazil, CarbonCopy is publishing it now because it offers a frank perspective on the political undercurrents that shaped the outcome of last year’s summit, and the deep frustration many Global South actors are bringing with them into the next round of climate negotiations.

The expectation at COP29 was to deliver a new, ambitious climate finance target post 2025. Civil society coalitions, including CAN International, had a clear demand. They wanted rich countries to provide $5 trillion annually in public finance to support climate action in developing countries. Instead, COP29 delivered a far more modest figure of $300 billion per year, to be reached only by 2035. For those in the Global South, this outcome fell well short of what is needed. It also reinforced a long-standing pattern of unfulfilled commitments from developed nations.

Essop’s views go beyond the headline figures. She gives a detailed account of how the negotiation process in Baku, which was marked by a lack of transparency, closed-door discussions, and a last-minute decision, pushed through without consensus. How it damaged trust and highlighted the structural imbalance that continues to define international climate diplomacy. She also discusses the broader shifts taking place within the global climate movement.

The threat to multilateralism is growing, and so is the gap between rich and poor countries. This conversation provides crucial context to how political power and influence are responding to climate impacts. It explains the disappointment that many developing countries and civil society groups felt in Baku, and the growing resolve not to accept incrementalism in Belém.

As COP30 approaches, this interview serves as a window into the evolving politics of climate action shaped by history, sharpened by inequality, and increasingly driven by demands for justice, not just in climate outcomes, but in how those outcomes are negotiated.

First, I’d like to ask you about your reflection on COP29. I know it’s a very multifaceted and very complex issue, but what are the biggest takeaways and the lessons from the experience?

The civil society movement including CAN was extremely disappointed with the outcome, especially on finance. This was our big fight for the year. This was a finance COP. We wanted to see a much more ambitious outcome. Especially recognising that the Global North for a very, very long time, was reluctant to take that responsibility under the UN Convention on Climate Change and the Paris Agreement to provide finance to the Global South.

As civil society, we went into this COP with a clear expectation that we should now finally get an ambitious outcome on climate finance, and a goal that is reflective of the needs and the reality on the ground in terms of what we would require to take climate action in the Global South. You know, the previous goal of $100 billion wasn’t based on any calculation of the need. And in turn, the Global North did not actually deliver the $100 billion. There’s been all kinds of accounting attempts to say they delivered, but the very definition of climate finance has not been resolved.

So, we, as civil society, largely in a big coalition, through the year, put the pressure on governments to at least deliver $5 trillion of public finance per year from 2025 to 2030, as only part of the climate debt that the Global North owes the Global South.

If you look at the needs and the different studies of what that means, $5 trillion isn’t actually ambitious. And others are saying we’re going to need more. But we, compared to where governments were at the time, wanted to put forward an ambitious number so that hopefully that would have pushed for more ambition amongst especially our global south governments, whose highest proposed amount on the table at that time, I think was from India, around $1 trillion. And even that included private finance, not just public finance. So we really wanted to centre the demand for public finance. The tactic here was to put forward a higher number so that we can pull up the level of ambition going into Baku.

And we did work with governments as well. Before we went to Baku, we particularly engaged with the Africa Group and the LDCs, etc. So that they can also get a bit more ambitious in what their expectations were.

The Global North did not put a number on the table until the very last moments of the negotiation. Of course, if people are negotiating and there’s no transparency about what the other parties are offering, that just firstly breaks down trust. Secondly, you don’t know what you’re working with. You can’t negotiate if there isn’t anything firm on the table. So I think that way of conducting a negotiation wasn’t one in good faith, and that disadvantaged developing countries.

It was clear when the first numbers came out, it was $250 billion [only to be reached by 2035]. The Global South reacted with complete outrage. We were outraged, too. And so that was the point at which civil society groups stood very firmly and said, “No deal is better than a bad deal”, and rather come back at this for the next COP.

And we engaged with the Global South, the G77+China (a bloc of 134 developing countries in the United Nations) and the different blocks in the G77 just to test that, would they be able to stand behind that. They were super angry about all of this.

But, with the dynamics of negotiations and the pressure generally, we understood that our Global South governments did not want a failure in a multilateral process, they really wanted to maintain the faith in multilateralism, because that is the only real space where the Global South has a voice. Maybe not equal power, but equal voice in the system.

So, yeah, that’s where we got to. “No deal is better than a bad deal” wasn’t something that materialised and they accepted that weak outcome.

Did the election of Trump play a role in the weak deal finally accepted by the developing countries because they thought that next year in Brazil there would be an even smaller chance for a deal to be struck?

That was the kind of justification from the Global North about why they couldn’t put more on the table. All their own domestic politics like the cost of living issues in Europe, the rise of the right wing, and the threat of Trump were used—”listen, take this or else it’s going to be worse” kind of thing. This was their messaging and narratives for why they can’t do any better in terms of their ambition.

In the end, governments make up their own minds about what they are willing to compromise on. As civil society, we were very disappointed with the outcome. But now that the decision is made, some countries have raised their objections and concerns in the plenary, but are they going to follow through with formal objections? So we don’t know where that stands. I doubt whether that will happen. I think people have now just accepted that.

But then there was a very concerning knock-on effect of such a weak outcome on finance, other areas of negotiation were sacrificed as well. So you would know the Just Transition Work Program, which is a very critical area in the negotiations and the negotiators had made progress on, was sacrificed and deferred to the next COP. Of course, the Mitigation Work Program (Note: In UN vocabulary, “mitigation” means emissions reduction and sequestration.) was always held hostage by outcomes on finance.

And then there is the process itself. I’ve been to too many COPs in my lifetime, including Copenhagen, which was already a really bad experience. But Baku’s process was unbelievable.

You would know that the negotiations just mainly went behind closed doors. The presidency convened bi-laterals or meetings with blocs, etc. And they all happened behind closed doors, in fact, in the presidency suite. And civil society did not have sight of what’s going on. It wasn’t transparent.

How did we get to the decision? What was traded off? Who were the ones that were blocking? You have to get information about what’s happening behind closed doors, so that we get a sense of things and we are able to respond. But then the presidency just gaveled through the decision. It was very shocking.

So I think that it was not just the outcome of the negotiations, but the process at this COP that was also seriously worrying. And we certainly don’t want to see that as setting a precedent for any future COPs.

So, do you think the UN climate regime is in need of reform, as what was called for during the COP?

There are areas that would require reforms, not just because of Baku, but for all our experience over the years.

One of them is the role of civil society in these spaces and what meaningful and inclusive participation of civil society looks like. I’ll give you a practical example.

Obviously, we’re not involved in negotiations, and I don’t think the UN system and governments are ready for that level of inclusivity, but when we are called upon to speak at the plenaries, we literally get only two minutes per Observer constituency.

This is the same for the environmental NGO (ENGO) constituency. We are one of two focal points for ENGOs, and we have a sister focal point which is DCJ [Global Campaign to Demand Climate Justice]. Because of that, the two minutes have to be shared. So, here you have two very big global networks literally having one minute each to articulate their views in a UNFCCC process.

And then, other participation, say when contact groups meet etc, it is up to the chair to decide whether we can speak or not. And to a large extent, if one party objects, we can’t speak. So, our participation there is not really meaningful. And that is why we’ve chosen to have a voice outside of the rooms.

That’s why you would see us putting that pressure on negotiations using the only other method that we can use and that is our action. Peaceful demonstrations outside the meeting rooms raising our voice and pushing negotiators to raise ambition.

The process in the UNFCCC has to be transformed in a way that gives us much more meaningful opportunities to participate. So, yes, I would say for civil society that’s one of the areas that we need to transform the UNFCCC.

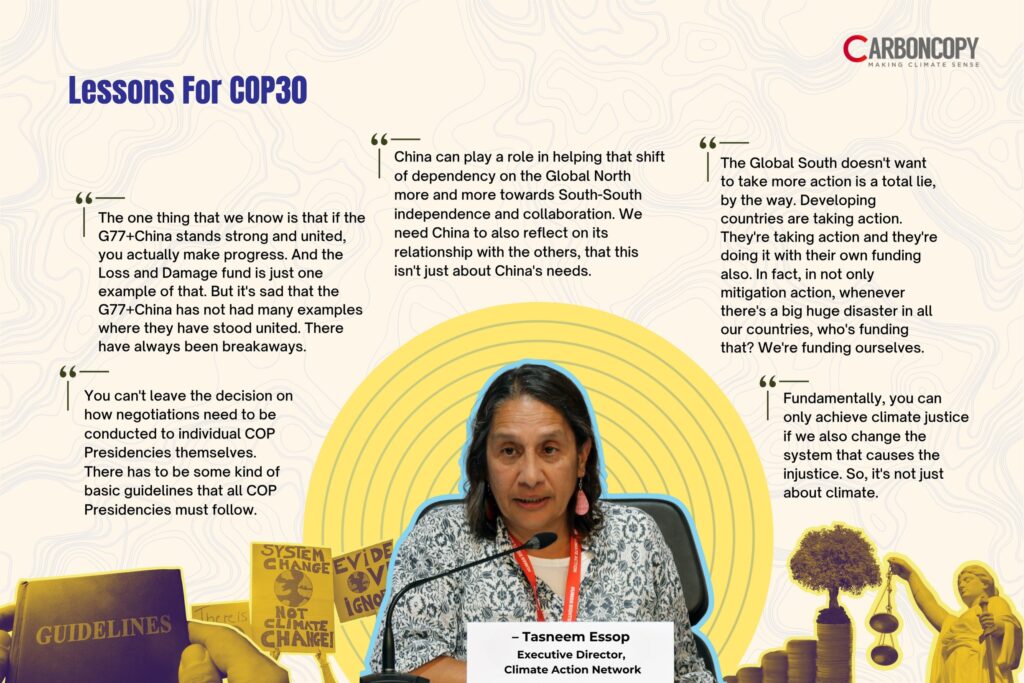

I think a second area of transformation would need to be this: you can’t leave the decision on how negotiations need to be conducted to individual COP Presidencies themselves. There has to be some kind of basic guidelines that all COP Presidencies must follow.

But currently we’ve seen that from one COP President to another COP President the approaches to the process are different. It’s too risky to do that.

Because of the particular way the UN climate regime makes decisions, which is called “consensus decision-making” in which there is no operational definition of what a consensus is, the presidency enjoys ample freedom to use the gavel. And some scholars are now arguing that there needs to be some degree of voting in making decisions at COPs, to constrain the presidency. What do you think of this kind of suggestion?

There’s one step before that. This is a party-driven process, so the presidency should not be driving the process in the way Baku did. We can’t have a presidency deciding what a party-driven process should look like.

The second one is this issue of consensus. It only takes one party to just object, and there’s no consensus. So you’re right, the rules of consensus have to be clearer.

And on the point of voting, I don’t know if it’s still on the agenda, but there used to be a standing agenda item put forward by Mexico on voting.

Especially when things are getting tougher and tougher in the multilateral space, maybe clearing up some of these operational rules would be really helpful, in a space deeply affected by geopolitics, where the levels of trust have diminished over the years. In such a context, I think the rules need to be clarified, and also the role of presidencies and what they can and cannot do.

There’s a host agreement signed between the UNFCCC and the presidencies, those host agreements should be looked at and reviewed and see whether it should be tightened up.

So I think there’s always room for strengthening and improving with the aim to become far more inclusive, far more transparent across the board and also, of course, to become effective. We don’t have time for this kind of slow pace with which this process is delivering results.

Could you envision the road ahead for global climate movement and climate diplomacy, considering what’s currently going on in the US and in Western democracies, with the rise of the far-right politics and oligarchy, etc.?

Look, the kind of power of oligarchies have always been there. What is happening now is, of course, they’re consolidating power and it’s becoming much more visible to us. It’s expanding that power and it is being bolstered by this emerging rise of right-wing politics across the board in the US, in Europe, but in other places in the world, even in the Global South.

So in such a context, for us, if the US and if other Global North countries take similar paths, I believe that we really have to look at the South-South collaboration much more strongly.

We probably need to reflect on the fact that for many years, and of course this comes out of the legacies of colonialism etc., the Global North has built this economic dependency on itself of the Global South. Meanwhile, we’ve also experienced, especially in the climate crisis space, that the Global North has put no real commitment to helping the Global South.

In such a context, I think the message is pretty clear. The Global North will never have the interest of the Global South at the front of their minds. They just haven’t proven that there’s a real track record around that.

Let me use another example.

During COVID, what did the Global North do? They went inward, they took care of themselves. They were not even willing to provide Global South countries with much needed vaccines. They weren’t even willing to share the intellectual property of their vaccines.

They’ve built close relationships with certain blocs for their self-interest. In the climate space, they’ve often tried to play divide and rule tactics with the G77+China bloc—for all the differences and challenges within the bloc—so that they have their interests protected.

The one thing that we know is that if the G77+China stands strong and united, you actually make progress. And the Loss and Damage fund is just one example of that. But it’s sad that the G77+China has not had many examples where they have stood united. There have always been breakaways.

So to what extent has divide and rule tactics actually worked in breaking down the unity of the G77 when they need to be united on some of the key issues? For me, looking forward, understanding that will have a huge impact when the US withdraws [from the Paris Agreement] like they’re doing now.

I think this is where now as the Global South—not only governments, but also civil society—we need to look at to start strengthening our solidarity, our collaboration, our independence in relation to the Global North. How do we start lessening our dependence? How do we start unraveling the apron strings to the North? If we were not so in debt, if we had sovereignty of decision-making, if there wasn’t all this interference when our resources are being extracted and going to the Global North, if we add sovereignty over all of the critical minerals and other resources, we could very much stand on our own two feet.

So, I think that it is time for us to look at the South-South collaboration much more strongly.

So how do you see China’s potential and current role in this? It’s quite a divided picture, right?

There are, of course, huge advantages and strengths in terms of China’s role. And then, of course, there are these challenges, the kind of extractivist role that they play. But China has been part of the Global South, and it is the only real powerful player in the Global South right now, if you look across the board, just in terms of its economy, in terms of its innovation, its progress and advancements in terms of technologies.

And so I think China can play a role in helping that shift of dependency on the Global North more and more towards South-South independence and collaboration. We need China to also reflect on its relationship with the others, that this isn’t just about China’s needs.

We need an alternative model because all of us have been caught up in the existing hegemonic model of economic development, of politics, and even culture. Many of the Global South countries aspire to be like Western countries, whereas I think we should be looking at alternative models and we should become the leaders where, in fact, the Global North looks to the South for leadership, for alternatives, etc. That’s my kind of a dream, if I can say that. It’s time.

I’d like to highlight the divergence within the Global South. COP29 may be remembered for the sharp dichotomy and “chicken and egg” dilemma where developing countries demand funding from developed countries, while developed countries require developing countries to first demonstrate their commitment to emission reductions.

But at the final stage of the negotiations, after their walkout protest, Cedric Schuster, the chair for Alliance for Small Island States (AOSIS), made it clear in a statement that as the most vulnerable developing countries, they actually wanted progress on both climate finance and mitigation, and were frustrated for being ignored.

And we would know shortly afterwards that Saudi Arabia, a developing country, was consistently blocking any language on fossil fuel going into the Mitigation Work Program document. Had Saudi Arabia not done this, maybe developing countries would have made some compromise on mitigation, and this compromise could have served as a leverage for more funding.

Do you think the kind of bipolar opposition between developed and developing countries disguised the conflicts within the latter and impeded progress on both agendas at COP29?

Now look, the divergences inside the G77 isn’t unknown to us. We know which agendas are getting driven by which blocs and which countries actually, like Saudi Arabia, plays a consistently bad role when it comes to any levels of ambition around 1.5, mitigation, etc.

For a long time, the conversations and the negotiations around mitigation actions have been caught up in this chicken and egg situation, with one side saying we can do more if the funds came, the other saying funds will come if you do more on mitigation. So which one comes first?

The NDCs are conditional on finance. You tell me whether the finance was delivered for that. So the governments of developing countries are saying, we can do this, if we had this funding, but they didn’t get the funding.

So, you know, often we also have to look at track records and good faith. We’ve had the Paris Agreement for 10 years now, right? Not translated into action.

You didn’t need a negotiation text for you to know that to stay below 1.5, you needed to stop your production of fossil fuels, especially in the North. And what did they do? They continued expanding production, expanding investment in fossil fuels. And at the same time, not really delivering the finance.

And so yes, of course, mitigation is important. But besides players like Saudi Arabia who might not have real commitments to it, there is also China. What has China done? They like to point fingers at China, saying they are not doing enough, but, in terms of renewable energy, it is the most advanced in the world.

So it’s not like there isn’t a commitment in Global South countries to do more.

Take my country, South Africa, we’ve articulated the need to shift away from our dependence on coal in the NDC. We have this JETP (Just Energy Transition Partnership), which is mainly loans-based, which puts a massive burden on the population in South Africa.

So in such a context, you can’t trade off the one with the other. You need to have delivery of finance which then allows for more mitigation actions.

And I think some parties will think, no, no, no, if we had just said something about transition away from fossil fuels, whatever, in this COP, it would have unlocked a lot more finance. I’m very skeptical about it. I just think where we landed on finance is where the North wanted it to be. It had nothing to do with Saudi Arabia blocking and the Global North wanting to see more action.

We must not look at one-off events. We have to look at track records. There’s no track record on this.

And then the other thing I want to raise is this idea that if you didn’t discuss the transition away from fossil fuels, it means that you’re not going to take action on it. Nobody, no parties have said we’re coming to rescind the decision that we’ve made at COP28. (Note: At COP28, parties for the first time in the history of UN climate talks agreed to “transition away from fossil fuel”.) So what excuse is there to not deliver on it? Do you need another discussion, or do you implement the decision? Everyone needs to go back home and deliver the transition away from fossil fuels. The decision has been made. What further decisions do we need to make about it?

COP28 decided all countries must transition away from fossil fuels. Here’s your decision. Now you tell us how you’re going to do it. You tell us what you need to do. You tell us why you’re not doing it. That’s the conversations that need to be had, but the decision was made already.

So I don’t know. People were saying this to me, “but what about the fossil fuel discussions, there’s no space to have that discussion”, but our existing architecture allows for accountability. There are the biannual communications or the transparency frame, etc.

The NDCs are also coming up. If COP28 said all countries must transition away from fossil fuels, surely your NDC would need to reflect it.

So, if the decision has been made last year, why not just do it again this year in exchange for leverage on finance? That doesn’t seem to be much of a sacrifice.

Just tell me, isn’t that a little bit of smoke and mirrors just to repeat the language of COP28 and that is leverage? I’m not sure if it’s a red herring, to obfuscate the fact that they owe the Global South funding.

And that the Global South doesn’t want to take more action is a total lie, by the way. Developing countries are taking action. They’re taking action and they’re doing it with their own funding also. In fact, in not only mitigation action, whenever there’s a big huge disaster in all our countries, who’s funding that? We’re funding ourselves.

So I believe that was an obfuscation. I couldn’t understand that, even in our own organization, people were like, “but there’s no space to discuss fossil, the transition away from fossil fuels.” But there is space to discuss it. Discuss it in NDC. We’re pivoting to implementation. Let us push very strongly that your plan to transition away from fossil fuel is included in there. And then for developing countries who need finance to help with that transition, put your finance needs in your NDC.

So I don’t think that was a real basis. It was not, I think that was an excuse and a justification to defend what was indefensible. And that was the low ball on finance in the way they did.

And then not only did they come with a low amount, but they also then go and shift responsibilities to the private sector, to MDBs (Multilateral Development Bank), and essentially start dismantling the convention and the Paris Agreement that requires developed countries to provide finance to developing countries.

So there are bigger things at play, not about who’s not willing to talk about fossil fuel phase-out.

That’s my sense. I’m very skeptical about it because, you know, as I said, I’ve been in these negotiations for a very long time, and there’s always some kind of justification for why developed countries are not delivering on their obligations.

Thank you for clarifying. I was just thinking that developing countries could have removed that “straw man” by just agreeing on stronger language on mitigation.

They would have shifted the goal posts. I promise you that.

We have been talking a lot about “the Global South”. The term has gained renewed prominence in recent years. But some scholars and commentators have disputed its validity. For example, the American political scientist Joseph Nye wrote in late 2023 that it’s “a misleading and increasingly loaded term” still in use only because of lack of an alternative shorthand, and others have argued for its retirement because they think it ignores the diversity of the world, and even called it “pernicious“. How do you define and see this term?

CAN doesn’t have a definition of Global South, so this is my personal opinion. So for me, the Global South is a political concept rather than a geographic one. And it is a concept that probably captures broadly where the Non-alignment Movement transitions from—the past of that colonial legacy, and the Non-aligned Movement then being the voice of the former colonies, and that are now called the developing countries.

And so, that sense of the political unity of those countries who have come through similar histories of colonialism, domination, independence struggles, of under-development and deliberately under-developed.

So, for me, the Global South has pretty much that political dimension embedded into it.

Have things changed?

We still have colonialism in some form or the other, right? People don’t think about neo-colonialism, but power relationships haven’t shifted.

There are new forms of colonial power. We just had a long conversation about it—how that power is being used today, the old colonial power is being used differently. It’s taken different forms, but that power relationship hasn’t really changed.

So, climate justice is very much about the balancing of power between North and the South. Otherwise, climate justice cannot be achieved.

It’s not only the balancing of power. Fundamentally, you can only achieve climate justice if we also change the system that causes the injustice. So, it’s not just about climate.

Again, for us to address this crisis and other crises, whether it’s inequality or the poverty crisis, that would need system change. Without that, we will be plastering over the existing problems. So, to achieve sustained climate justice, you would need to change the system.

JIANG Yifan is a freelance journalist and consultant based in China.

About The Author

You may also like

Brazil Set 60-Day Deadline for Fossil Fuel Phase Out Plan

What COP30 reveals about the next phase of multilateralism

The G20 Has Outrun COP on Climate Finance

India needs targeted public finance to scale green steel production

India Pushes for Critical Minerals Circularity and Collective Action on Climate at G20