Developed nations continue stifling discussions on setting a standard definition despite push from developing counterparts

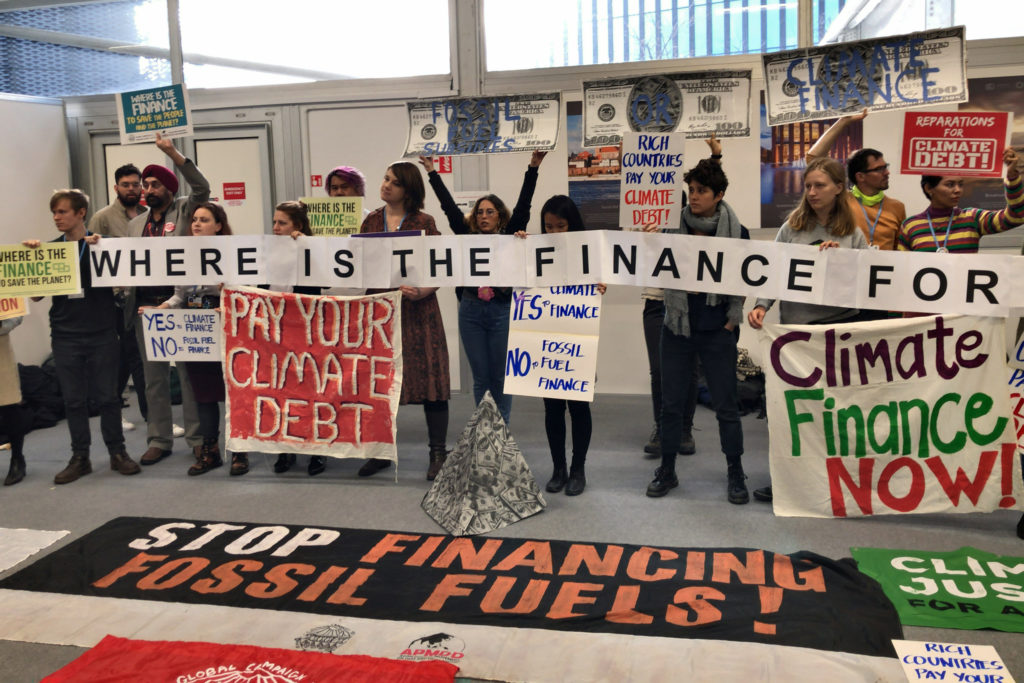

For developing nations of the world, success at this year’s COP hinges heavily on being able to secure guaranteed flows of finance from the developed world for ambitious climate action. Weeks before the commencement of the climate conference, developed countries scrambled to piece together the $100 billion per year they promised a decade ago. Despite the US and the EU indicating intent to raise their contributions, the $100 billion figure is yet to be reached.

Now, with only a few days before COP26, two worrying updates have the potential to paralyse the entire meet.

First, on October 25, 2021, the developed world released a “climate finance delivery plan” that said it will deliver on its pledge to provide the $100 billion per year by 2023, three years later than originally promised.

The second development pertains to the quality and form of finance available to the developing world. During a recent meeting of the UNFCCC’s Standing Committee on Finance (SCF), developed countries stifled discussions on the definition of climate finance, crucial to the determination of finance flows. The ambiguity surrounding a common definition of climate finance opens the possibility for developed nations to meet their financial obligations through their own respective criteria, even if the goal is increased to a new figure beyond $100 billion. The lack of a definition substantially reduces the quality of finance reaching developing countries.

The climate finance conundrum

Ever since the conversation began in 2009 on the $100 billion figure, a number that came out of thin air, developed nations have kept the climate finance promise ambiguous. The matter had reached fever pitch in 2015 when current American climate envoy John Kerry threatened to take the US and the developed world out of the agreement if developing countries pushed to make climate finance legally binding as the final agreement text was being negotiated.

Post the Paris Agreement, any attempt to revisit the definition of climate finance and revise commitments have been met with steadfast refusal from the developed world. The confusion around finance serves the rich nations well as it allows loans and private capital to be passed off as a part of the commitments towards mobilising climate finance. These fluid metrics of evaluation ignore the arrangement that money was mostly supposed to be ‘new and additional’ to their Official Development Assistance and was supposed to come in the form of public grants.

Now, years later, the question around climate finance is once again on the boil, with the developed world pushing for an extension of the deadline until 2023.

“Developed countries unilaterally decided this [newly launched climate finance delivery plan] report and made this delivery plan using their own undeclared data and their institutions,” Zaheer Fakir, one of the lead coordinators for the African Group of Negotiators on climate change, told CarbonCopy.

“Yet, developed countries are demanding even greater efforts from developing countries through enhanced NDCs and making net-zero commitments.They are talking of ambition, yet no such ambition from their side exists when we deal with finance,” Fakir added.

As per the Paris Agreement, $100 billion was supposed to be the 2020 goal. The goal for 2021-2025 was supposed to be a new figure with $100 billion as the floor.

According to the Paris Agreement, “… in accordance with Article 9, paragraph 3, of the Agreement, developed countries intend to continue their existing collective mobilization goal through 2025 in the context of meaningful mitigation actions and transparency on implementation; prior to 2025 the Conference of the Parties serving as the meeting of the Parties to the Paris Agreement shall set a new collective quantified goal from a floor of $100 billion per year, taking into account the needs and priorities of developing countries..”

“One sets a floor as the minimum and aims for higher/ceilings so even with minimum progression, we should have been at $110 billion or $120 billion,” Fakir said.

He added that rich countries claim that it’s not them who have made inadequate effort. The shortfall in meeting $100 billion has been a result of poor mobilisation of private finance, they said. “Get MDBs [multilateral development banks] to do more, to shift their activities, and attach higher importance to support activities that focus on shifting finance flows in accordance with Article 2.1(c) of the Paris Agreement.” [The article mandates ‘making finance flows consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development’]

Pointing to the farce of transparency, Fakir said the new report identifies the importance of transparency, but does little to address it. “No indications of the pledges or any form of detailed data that justifies their assumption” have been provided in the plan. Furthermore, they suggest that reporting, monitoring and assessment of the $100 billion between now and 2025 to be conducted outside the UNFCCC multilateral process, and propose that this be done through state apparatus at the behest of “donor” nations, with inputs from recipients.

This duality in the approach of the rich nations is pushing the “a grand bargain” that is the Paris Agreement to the brink of “falling apart”, Wael Aboulmagd, a diplomat from Egypt and a seasoned negotiator, who has represented the interest of the Global South at UNFCCC, told CarbonCopy recently.

Rich nations curtailing progress on climate finance definition

A new UN report on finance assessed that the actual needs of the developing countries could run into trillions of dollars—far beyond the amounts previously recognised officially.

In the absence of a standard definition of climate finance, developed nations largely overstate the actual flow of capital. A 2020 Oxfam report said less than a third of the public climate finance reported in 2017-2018 by developed countries was climate-specific.

Further, a large part of the finance that has been accounted for is in the form of loans and interest rates, which risk pushing several poor countries into a debt trap. The Oxfam report noted that out of the reported climate finance in 2017-2018, nearly 77% are loans. About 40% of these loans were also non-concessional, carrying market rates of interest.

The remaining 60%, which has been tagged with “concessions”, was also flagged for inflated numbers. Exploring this further, if a non-concessional loan figure is provided at the market interest rate of 10% to a poor country and a concessional loan at 8%, reason would state that the savings from 2 percentage points of interest is what should qualify as climate finance rather than the entire amount loaned.

This has been India’s stand at the negotiations. According to Indian negotiators, only public grants, unrequited equity and grant-equivalent values of loans should be counted as climate finance. The proportion of loans in the overall public climate finance pie increased from about 72% in 2015-2016 to 77% in 2017-2018. In the same time frame, grants decreased from 25% to 21% of the total.

All of this leaves poorer nations in a tight spot. Thus, the demand for clear demarcations of the nature of finance has gained importance as a part of efforts to ensure transparency and accountability from the developed world.

Due to the lack of clarity currently surrounding the definitions of finance, there is little congruence between numbers published by various assessments. “The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), a grouping of developed countries, comes up with their own numbers, Oxfam will have a different figure, and every other bank would have their own figures,” said Fakir.

‘Single definition not useful’

There has been a long history of developed nations evading the discussion on the definition of climate finance.

In Madrid in 2019, at the COP25, developing countries pushed for a discussion on climate finance but the US, Japan and the European Union opposed the move. Thus, in the final decision taken at the 2019 negotiations, countries were only invited to submit “their views on the operational definitions of climate finance”, which would be considered by the UNFCCC’s SCF for its fourth round of 2020 biennial assessment (BA report) of climate finance flows.

At the SCF meeting that took place this year, some recommendations put forth with the summary became an issue of contention between the developing and developed worlds, Third World Network (TWN) reported.

“Some Parties noted that a single definition would not be useful or should be broad enough to cater for the dynamic and evolving nature of climate finance …(while) some Parties pointed to the use of a classification system or taxonomy rather than a single definition. Other Parties noted how the lack of a common definition affects the ability to track and assess the fulfilment of the obligations of Annex II Parties under the Convention and those of developed country Parties under the PA,” states the summary text per TWN report.

Members of the developed countries including the US, EU and Switzerland argued that the COP25 mandate was only limited to the preparation of the 2020 BA report, which had happened, and thus it was a “one-off exercise”. There was no mandate foreseen for the SCF to continue work on a definition.

Suggesting that the recommendation be striked-off, the US and Switzerland also said that the Paris Agreement allows each party to self-determine what makes climate finance and that “imposing one definition of climate finance would mean renegotiating the bottom-up structure” of the Paris Agreement.

Developing countries, however, were strongly in favour of including the recommendation on the need to have a standard climate finance definition. Since the lack of it has been posing several challenges for years now, particularly in gauging actual flows of finance.

After an intense exchange on this and some other recommendations included with the 2020 BA report summary, and in the lack of consensus, the 2020 BA report summary was adopted and sent to COP26 without any recommendations.

“When it comes to the UNFCCC multilateral process, the OECD methodology is forced upon us. But OECD is an institution of developed countries, we are not a party to this,” said Fakir, who was also a part of the SCF meeting.

OECD uses ‘Rio markers’ to assess their finance flows. “The issue we found with these markers is that a lot of things that are classified as significant mitigation actions had nothing to do with mitigation. For example, if you’re hosting a workshop on climate change, OECD can classify it as a significant mitigation action. So what we wanted to do and what the SCF has been trying to do is come up with a common understanding and definition about how we quantify what climate finance is, and how we account for it,” said Fakir.

The intention of current discussion is not to negotiate a new definition of climate finance, that will take forever. But it is about every party being on the same page. So when the “developed world is counting apples, we can also count apples, and we don’t count the apples, pears and bananas together,” he added.

About The Author

You may also like

Climate change impacting GDP and capital globally, poor countries most affected

Developed countries push to move L&D Fund out of the UNFCCC

World Bank and IMF annual meetings 2023 begin today. Here’s what to expect.

India’s Green Bonds framework comes with a lot of promise, but also grey areas

15th Biodiversity COP kicks off in Canada, fate of the Global Biodiversity Framework hangs in balance