The update highlights the dire need to step up regulatory and implementation efforts in India and other South Asian countries in order to rein in the adverse health impacts of escalating air pollution levels from development projects

First, the bad news. Despite significant steps taken by some countries towards curbing particulate air pollution, the issue continues to cut global life expectancy by two years, according to a new study.

The update on Air Quality Life Index (AQLI) published by the Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago (EPIC) on July 25 finds that an average person can be exposed to 29 µg/m³ of particulate pollution concentrations – three times higher than the limit of 10 µg/m³ that has been set by the World Health Organisation (WHO). This means that if we continue to be exposed to such levels, the global life expectancy would be reduced by 1.9 years when compared to a world where WHO guidelines were met by all countries.

Particulate air pollution continues to be the primary risk to human health, according to the study. The risk is slightly more than cigarette smoking (which reduces global average life expectancy by about 1.8 years), and much more than other health risks such as alcohol and drug use (11 months), unsafe water and sanitation (7 months), HIV/AIDS (4 months) and malaria (3 months).

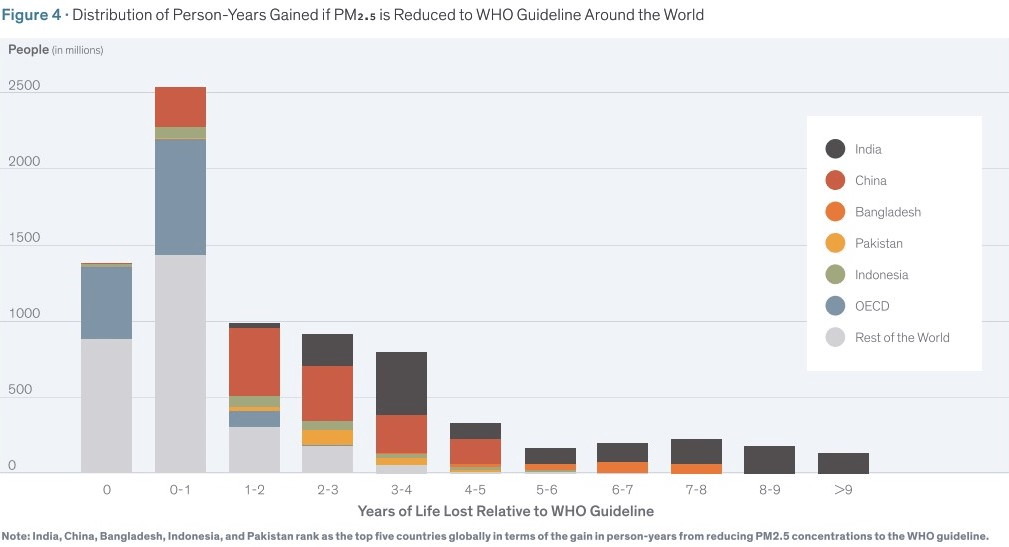

One of the main reasons why air pollution is on top of this list is the sheer numbers that are exposed to toxic air. The study states that 5.9 billion people (79% of the global population) reside in areas where the PM 2.5 levels far exceed the WHO guidelines.

But now for the good news. The study finds that stringent public policies aimed at curbing air pollution actually work, citing the examples of China and the US. It calculated that if the levels of particulate pollution concentrations had remained unchanged since 2011, the average global life expectancy would have been far lower – by about 2.6 years – compared to a world where WHO guidelines were met. However, a 20% drop in pollution levels globally since 2011, thanks to robust policies, shaved off 8 months from that calculation.

South Asia’s population-dense countries are a big worry

More worrying, however, is the source of the polluted air. According to the study, four densely populated countries, Bangladesh India, Nepal and Pakistan – which account for nearly one-fourth of the population — are also the most polluted. The study finds that residents of these countries would have their live expectancy cut short by five years if current levels of pollution persist. The main culprits, according to the study, are industrialisation, population growth and economic development in the past 20 years.

Individually, this number goes up even higher. In India, for example, 248 million residents of the northern region of the country are expected to lose more than eight years of life expectancy if 2018 concentration levels continue to persist. If India cleaned up its act, the study stated, that the life expectancy of its total population would rise by 5.2 years.

The study even mentions Indonesia, which is also suffering from the toxic effects of rapid growth, along with an additional problem – forest and peatland fires. In the cities of Palangka Raya in Central Kalimantan and Palembang in South Sumatra, the study calculated life expectancy for the residents of these cities to be four years lower than what it would be if the long-term average particulate matter exposure adhered to WHO guidelines.

What can India do?

The drastic drop in pollution levels during India’s COVID-19 lockdown offered a glimpse into what can be possible. But a stringent lockdown is hardly a practical solution and India needs to think long term to get back on track. The government did launch the National Clean Air Programme (NCAP) as part of its ‘war on pollution’, as the study pointed out. But the programme has been dogged with complaints of diluted norms and ineffective implementation ever since its inception. Its major problems continue to be the lack of a legal mandate, unclear timelines and zero accountability. So far, 102 cities have submitted clean air plans, but 90% of them have no budgetary allocation.

The Indian government itself has been fairly wishy-washy in its stance on air pollution. While it has announced a ‘war on pollution’, it also recently launched an auction of several coal blocks for commercial mining. Even existing coal mines are reluctant to adhere to air pollution guidelines. The mandatory installation of Flue-gas desulfurization (FGD) technology to control sulphur dioxide emissions, for example, has been fraught with delays and demands for extensions by coal producers, who have sighted everything – from lack of space to the COVID-19 pandemic – as reasons for not adhering to the order.

Even the highest court of the country, the Supreme Court, relaxed the NOX emission limit for coal-fired power stations commissioned between December 2003 and 2016 from 300 mg / Nm3 to 450 mg / Nm3 in July this year. The order was based on a government recommendation in August 2019 to water down emission limits.

Such moves have sadly put the NCAP’s aim – to achieve a 20-30% reduction in the ambient PM 2.5 levels by 2024, when compared to 2017, in India’s most polluted cities – in jeopardy.

How policies have worked in US, China

While India struggles with diluted policy decisions, the study highlighted countries where air pollution plans have made a difference. It cites the US, Japan and Europe – which account for 2% of the health burden from air pollution — as prime examples of what can be. Years before India’s NCAP, the US enacted the Clean Air Act in 1970, which established the National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS). This was a guideline for the maximum allowable concentrations of particulate matter along with other pollutants. As a result of this, particulate emissions have recorded a staggering drop over the years because of which Americans today are breathing 66% less particulate pollution than they would have been in 1970.

Europe has set a benchmark as far as air pollution standards are concerned and also formed the European Environment Agency in the mid-1990s that gathers and provides independent data to policy makers. As a result of the region’s pro-activeness, Europeans are exposed to 41% less particulate pollution than they were 20 years ago, and have gained nine months of life expectancy because of it.

Even China, the study claimed, has succeeded rapidly in bringing down particulate pollution. Its National Air Quality Action Plan is estimated to have led to an average 39% decline in particulate pollution exposure across China between 2013 and 2018.

Now compare this data to that of Bangladesh, Pakistan, India and Nepal. The average resident of these four countries is exposed to particulate pollution levels that are 44% higher than two decades ago. What this study proves is that the time has come for a foggy and groggy South East Asia to finally wake up and smell the coffee.

About The Author

You may also like

Rise in temperature leading to increased suicide rates in US, Mexico: Study

14.5 million lives may be lost by 2050 due to climate change: WEF report

Delhi-NCR most polluted region in India, Karnataka the cleanest air in India: Report

Outdoor air quality chronically underfunded, finds State of Global Air report

PM2.5 shortening average life expectancy of Delhi residents by almost 12 years