CarbonCopy spoke to three artists using comedy to address climate issues in a world of changing conversational landscapes, varied audience, social media, trolling, and censorship

“Greta (Thunberg) is from Sweden. The country is famous for two things. One, Ikea — the furniture store and second, Volvo — the car company. Greta hates cutting trees… and driving cars. Sweden is like ‘Oh, damn!’” And the audience breaks out into a chuckle.

Stand-up comedians talking about climate and environmental issues is not common in India. However, Shridhar Venkataramana, a Mumbai-based comedian, is changing the norm. Be it the cold wave in Delhi or the Bengaluru flooding, Venkataramana jokes about it all.

For instance, it would be absurd for someone in the Global North to joke that decreased visibility because of a cold wave can lead to lesser crimes. But for someone in Delhi, this joke may not seem so far-fetched. During one of his performances, Venkataramana rides on this social difference with this one-liner on criminals who “may want to kidnap you… but can’t because they cannot find you,” he jokes.

Talking about this spin on a common man’s perception of these climate and environmental issues, Venkartaramana explains, “It largely has to do with how people look at these issues. I’m not an expert here to preach about what is to be done, but these are obvious issues and people relate to news like this. I try to consciously make sure that there’s something to think about while I’m making jokes.”

Finding the voice

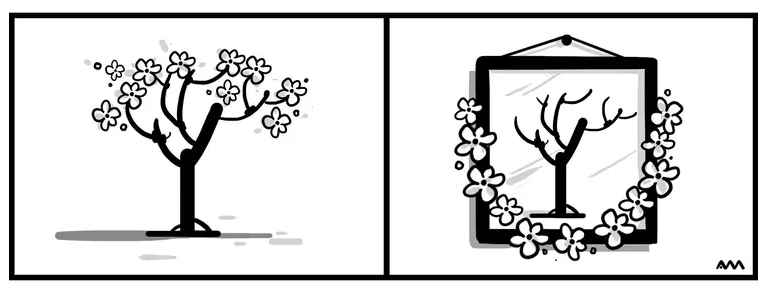

Not everyone speaks to an audience through a microphone. Ashvini Menon, a comic designer based in Mumbai, began addressing climate and environmental issues in her work when she couldn’t directly speak to people about it. “I saw how my own actions were consequential to the bigger picture and realised the gap between what was ideal and what was the actual way of life. I couldn’t go and talk to people like that, but I found that voice in the comics that I drew,” she says.

What started with sharing comic strips on Facebook, soon turned into a weekly feature called ‘Ecotism’ in the Hindu, which ran for two years.

Menon’s work focused on general sustainable-development issues faced in the country. “We were not issue-specific and I used it to my benefit. I realised that if I make my communication more open, I’ll have a wider audience and it will open doors to more conversations,” she adds.

Evolving audience (or not)

Back in 2014, when Menon was starting out, she felt that people did not talk about climate and environmental issues that much. So her focus has been on building general awareness. Now, however, she believes that people are more aware of such issues.

Venkatramana, too, has acknowledged that the audience has appreciated him bringing these issues to light. “People who are concerned about issues like global warming and climate change have appreciated the fact that I made those jokes,”he says.

However, Rohan Chakravarty, a cartoonist and illustrator, begs to differ. Creator of Green Humour—a series of cartoons, comics and illustrations on wildlife and nature conservation. Chakravarty feels that a few years earlier, people were open to engaging with the opinion of the other person. Now they are “restricted to their own bubbles, which largely has to do with the political environment of the country”. As a result, there’s a lot of pseudo science and climate denial ,which just can’t be countered, he says.

Getting published in national newspapers introduced Menon and Chakravarty to a more diverse set of audience, beyond their usual circles. This is because culturally, newspapers have always had the space for cartoons and the audience there understood the purpose of them, Chakravarty says.

“The audience reading newspapers is better equipped to understand comics and cartoons. Even if they disagree with me, they are critical in a constructive way which helps me understand my art. But when it comes to social media, it is just incessant trolling and unconstructive criticism,” he adds.

Citing an example of one of the comic strips he did for the Times of India, Chakravarty further explains how he gets trolled online on questioning authorities, like this cartoon below, which merely questioned the status of habitat conservation in the country.

“They say things like ‘You are just a cartoonist. Who are you to question those whom people have elected to power?’ The polarisation that social media has done has decapacitated our understanding of satire, humour and the role of cartoons in society,” he laments.

While trolling has become an inherent part of social media now, for comedians like Venkataramana, social media works wonderfully for sharing bite-sized reels packed with punches.

Toning it down

Artists are free to operate social media accounts as they wish. Things get tricky though when one ties up with national news outlets. According to Chakravarty, censorship has grown considerably over the years. “It has grown to the extent where newspapers today have to tell me to tone down the message. Anything pointing fingers at authorities is met with a lot of fear and hesitation”, shares Chakravarty.

Even internationally, he has had similar experiences. Chakravarty has covered the last two COPs live, drawing some hard-hitting cartoons.

While covering COP26, Chakravarty took to Instagram to share how he was “politely asked to tone it down or lose the prospect of having his cartoons displayed.”

“A lot of cartoonists say that we are leftist or rightist. I say that a cartoonist should only be a sadist,” chuckles Chakravarty.

For Menon, however, this sort of censorship has not been a problem since her work was not issue-specific. But she had to self censor quite a few times when it got too “hopeless.”

Building hope and joining the dots

As a creator, Menon has struggled sometimes to maintain balance between the truth and hope while thinking of cartoon ideas that may seem “too dark or depressing.” But she doesn’t want people to feel hopeless or that everything is a lost cause. Her concern right now is to keep hope alive. “I definitely want to celebrate nature and remind people of the goodness of what we have,” she adds.

Currently, she draws for The Protected Area Update, a bi-monthly newsletter carrying news and information from Protected Areas in India and South Asia.

According to Chakravarty, during a 3-hour long session at COP26 on mitigating climate change in developing nations with a focus on areas around national parks and nature hubs, the word ‘biodiversity’ was used merely once. Did he really count? “Yes, I did,” answers Chakravarty. “The fact that people in such powerful positions and administrations can’t even make the connection between climate change and biodiversity is really shocking.” This is the gap the cartoonist aims to bridge. Also, as a lot of climate science is restricted to journals which are not easily accessible, Chakravarty aims to make it reach those who matter—today’s climate-affected common man.

Gutentor Simple Text

About The Author

You may also like

Win for small island states as top maritime court calls GHG emissions a form of marine pollution

Climate warming is altering food webs and carbon flow in high-latitude areas: Study

Rise in temperature leading to increased suicide rates in US, Mexico: Study

Seafood to lose nutritional value due to climate change: Study

14.5 million lives may be lost by 2050 due to climate change: WEF report