When Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced the 3-week lockdown in response to the global COVID 19 pandemic last week, the first concern that needed to be addressed was that food supplies would continue unhindered and no one would go hungry. Within days, finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman came out with immediate relief measures assuring one kilogram of pulses per month per household and five kg of wheat or rice per month per person to 800 million people for the next three months over and above what they have been getting through other sources.

Far from being only India’s headache, the global pandemic has exposed the vulnerabilities of the food supply chains across the world as movement of goods and labour grind to a halt. While prices of staples have thus far withstood the COVID disruption and remained stable, the Food and Agricultural Organisation has vocalised fears of food supply disruptions in April and May that could trigger an increase in food prices. Consulting firm Fitch Solutions have also highlighted “risks at all levels of the supply chain, from production to trade.”

The current chaos in global food supply chains due to the pandemic is adding to stress that was already created by other environmental disasters unfolding around the world such as the locust outbreaks in Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia. Even without the additional shocks of events such as the current pandemic (which are also projected to increase in frequency), the Inter-governmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has projected significant increases in food prices as yields of major crops fall due to increasing temperatures. The risks to food supply and security from the current combination of threats, including the high probability of prolonged droughts in Australia, South Asia and Africa, highlights the need to stress the importance of building resilience into global supply chains as a part of the climate change response.

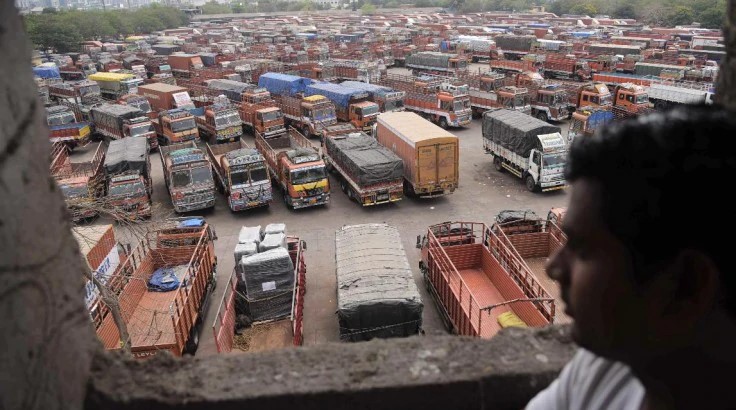

For India, while current foodgrain stocks stand at 77.6 million tonnes (MT) of staples and around 3 MT of pulses, more than three times the minimum buffer to be maintained, the current lockdown is exposing vulnerabilities in the food supply chain. According to community survey platform Local Circles, food supplies in India started getting hit even before the lockdown was officially enforced. According to their data, the percentage of customers unable to buy essential goods through e-commerce services between March 20 and March 22 was 35%, and it shot up to 79% in the March 23-24 period. At the retail store end, 17% of customers were unable to buy essential goods on March 20-22, and 32% on March 23-24. The situation has only gotten worse. News reports from several states point to a constricted flow of food supplies amid arbitrary police action.

What’s more, the lockdown is likely to adversely affect the Rabi crop harvest amid labour shortage, lack of transport facilities and closure of mandis, despite government notifications allowing discretionary agricultural work. In parts of the country, the shortage of food supplies in the market, coupled with a shortage of cash, has seen a return of the barter system. The fear now is that if the COVID battle turns out to be a prolonged one, the effects could very easily spill over to India’s Kharif crop cycle, with limited flow of agricultural inputs expected to affect sowing and yield.

While global supply chains have been severely affected by the limited flow of goods, Europe and the US are bracing for a massive agricultural hit as labour shortages loom as a result of strict travel restrictions. In Southeast Asia, major palm oil producers have closed operations for fear of transmission among workers. As countries respond to disruptions in food production and supplies, there has been a move to stockpile domestic produce. Vietnam, the world’s third-largest exporter of rice, and Kazakhstan, the ninth-largest exporter of wheat, have both suspended all exports of food grains in order to shore up their stocks. According to the World Bank, such measures between 2006 and 2008 led to a 45% increase in rice prices and a 30% increase in wheat prices.

But it’s not just the pandemic that’s negatively affecting food security around the world. In Africa, the Middle East and South Asia, locust invasions that date back to 2018 are devastating crops and threatening food security. The invasion of biblical proportions could affect the food security of over 20 million people and is threatening a famine in parts of Africa with rising food prices. The current health crisis is likely to make the locust invasion worse as supplies of vital pesticides get hit and governments struggle to cobble up finances to fire-fight on two fronts simultaneously.

Current global supply chains, especially those of food, are complicated networks of myriad links. Disruption in even one could bring the entire system to a halt. A new study published this fortnight shows how prolonged climate disruptions in one region of the world could see a large-scale collapse of the global food order and subsequent sky-rocketting of prices. This vulnerability is a feature of our current civilisational lock-in in which stresses on one front increase pressures on other fronts such as supplies of oil and water, and large-scale cooperation across the world without which the system could not exist. The COVID pandemic, linked to biodiversity and habitat loss, and the locust invasion, linked to weather disturbances in the Arabian Peninsula in 2018, give us a primer of the kind of disruptions climate change holds in store for our economic system.

The impacts of climate and environmental change on society and economy are likely to be non-linear with a series of tipping points that multiply individual impacts several fold. While mitigating technologies such as renewable energy, electric mobility and emission reducing interventions in industry have been central thus far to climate action, the need to increase adaptive capacity and resilience in networks have by and large gone under the radar. The current shocks to global food supply should be a timely reminder for governments to refocus efforts towards adaptation, not only in production but also in logistics and storage, which must start with the strengthening of local, regional and domestic supply chains in order to culminate in robust food sovereignty and security that goes beyond merely record volumes of food grains in buffer stocks. Unfortunately, this would also require a comprehensive rethink of current global economic structures. The preservation of societal and civilisational order might well depend on it, but whether governments are brave enough to confront this challenge, only time will tell.

About The Author

You may also like

India’s EV revolution: Are e-rickshaws leading the charge or stalling it?

Is pine the real ‘villain’ in the Uttarakhand forest fire saga?

NCQG’s new challenge: Show us the money

India’s energy sector: Ten years of progress, but in fits and starts

9 years after launch, India’s solar skill training scheme yet to find its place in the sun