The NDA govt is looking at hydel power to balance the grid as it moves away from coal, but as past attempts have proven, this will be easier said than done. This is part one of a three-part series.

Once again, India is in the throes of a dam-building enthusiasm. Not only are old, stranded projects being revived, newer ones are being commissioned as well.

Just last year, the BJP-led NDA government announced fresh dams in Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh. In Sikkim, there is speculation that a 520 MW hydel project at Dzongu will be revived. In Kashmir, so many dams are being built that the region’s hydel power output will double from the existing 3,504 MW to 7,001 MW.

The biggest of these pushes, however, is in Arunachal Pradesh. In December, 2021, the Union power ministry sanctioned 29 hydel projects—adding up to 32,415 MW—in the state.

But hidden underneath these announcements is a state-financed gamble over hydel’s role in India’s decarbonisation.

As the pressure to cut emissions rises, India will struggle to add new thermal power plants. At the same time, alternatives to coal-based power are still imperfect. Renewables are cheap, but not available all day. Gas, as CarbonCopy has reported, is too expensive to be competitive. Nuclear is too small in scale—and, as agitations like Kudankulam showed—runs into intense opposition.

That leaves hydel power. It, however, is costlier than solar. And so, instead of having it compete with low solar tariffs, the NDA government wants to use hydel for peak power and grid-stabilisation. “Renewables come with intermittency and so we will need hydel to balance the grid,” said Vinay Shrivastava, a former executive director (western region) of India’s Power System Operation Corporation (POSOCO), a state-owned enterprise, which manages India’s electricity grid.

And so, not only does the BJP-headed NDA government want to push India’s installed hydel capacity to 70,000 MW by 2030—a 50% jump from the current 45,700 MW—it’s also readying a large push on pumped storage. As energy minister RK Singh told the Economic Times, the NDA has also identified 63 projects adding up to a generating capacity of 96,000 MW.

Hard-wired into this push, however, is a bet that hydel can hold its own against emerging storage technologies like battery energy storage systems (BESS) and electrolysers.

India pushes hydel again

This is not the first time India is trying to amp up its hydel power capacity. In 2003, too, the country had announced an ambitious plan—to treble its hydel power capacity.

At a time when India’s dams produced a little over 26,000 MW, the then-ruling NDA government, headed by Atal Behari Vajpayee, said it would set up 162 new hydel projects, adding up to 50,000 MW by 2012.

That number climbed higher still. A clutch of states signed more MoUs than they needed to. Uttaranchal, meant to add 5,282 MW of fresh capacity, signed MoUs for 27,450 MW. Arunachal Pradesh, set a target of 27,000 MW, signed MoUs for 43,118 MW. Sikkim, given 1,469 MW, signed MoUs for 5,284 MW.

Himachal Pradesh, which was expected to add 15 projects adding up to 3,328 MW, signed MoUs for 53 projects in one part of the state alone—Kinnaur. By 2014, it had plans for as much as 13,813 MW of fresh capacity.

A speculative bubble had formed. Attracted by the prospect of owning a hydel project—with its promises of low running costs and government-mandated fat margins—construction companies and other newcomers to the energy sector were clamouring to get in. Knowing most of these projects wouldn’t come up, but seeing an opportunity for rent-extraction, political parties in power states such as Arunachal Pradesh and Uttaranchal began charging for MoUs—even with untested companies—and commissioned as many dams as they could.

By 2013, Arunachal Pradesh had signed MoUs for 153 dams. To put that number in perspective, the state has just four major river basins—Subansiri, Lohit, Siang and Kameng.

What happened next is well known. Pushed without considering their social, environmental or even economic feasibility, most of these dams never got made. Work began on some, but halted due to local opposition. Others never started construction due to the absence of necessary infrastructure such as roads and transmission lines. Others, signed by speculators hoping to offload MoUs to serious players, found themselves scuppered as buyers wisened up.

In all, each state failed to add the capacity than its MoUs promised, and India missed Vajpayee’s target as well.

Vajpayee had wanted the country to add 50,000 MW by “the 12th Five Year Plan”–2012. In reality, the country added just 12,223 MW. Little changed in the eight years that followed. As a 2020 report in Hindu BusinessLine says: “Only about 10,000 MW of hydropower could be added over the last 10 years,” taking India’s installed hydel power capacity to 45,700 MW.

A battle over storage

Today, as the country tries again, it has jettisoned parts of the old approach.

For a start, projects are being given not to the private sector, but to public sector undertakings (PSUs).

The 29 projects coming up in Arunachal Pradesh, for instance, have been shared between India’s four hydro PSUs—National Hydel Power Corporation (NHPC), North East Electric Power Corporation (NEEPCO), THDC (formerly, Tehri Hydro Development Corporation) and SYVN (Satluj Jal Vidyut Nigam)—with each getting a river basin.

In Kashmir, too, all MoUs have been signed with NHPC. “We are back to PSU-driven development in the hydel sector,” said Jayant Kawale, a former head of Jindal Steel and Power’s hydel unit.

In addition, large hydel projects have given renewable energy status enabling new projects, as joint secretary AK Verma wrote in Hindu BusinessLine, to “receive concessions and green financing available to RE projects”.

To ensure hydel still has buyers—despite solar’s lower tariffs—the NDA has introduced Hydel Purchase Obligations. Like the Renewable Power Obligations, which compelled DISCOMs to buy solar and wind, these push hydel. “Everyone wants to schedule the cheapest power,” said Shrivastava. “With so much infra cost, if the cost of hydel is Rs4, the cost of solar is Rs2. No state will buy hydro. If some state has put up 2,000 MW of hydel, it will become a NPA [non-performing asset].”

In tandem, the debt repayment period for dams has been hiked from 12 years to 18 years and their project life has been extended to 40 years—both give promoters more time to retire loans, and ergo, make lower tariffs possible.

That said, even if some old challenges have been addressed, others persist. These include social, environmental, geological, geopolitical (China) and infrastructural challenges that dam-building runs into.

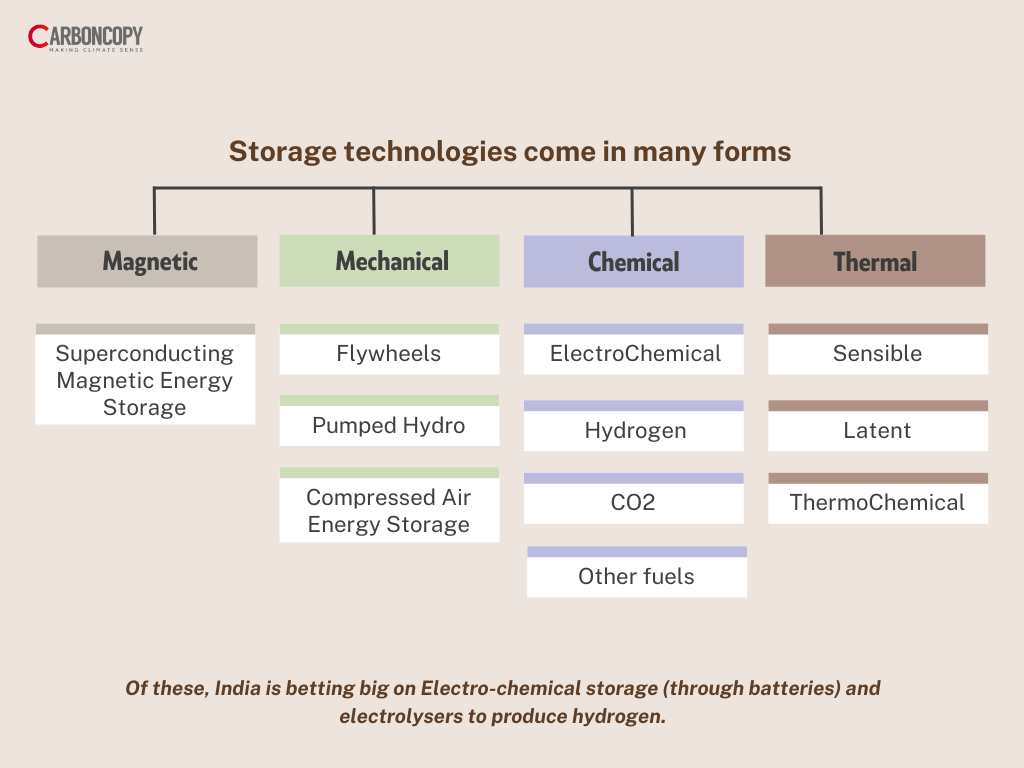

And then, there are newer challenges. India’s pushing hydel storage at a time when the world is making a big push on rival storage technologies like batteries and electrolysers.

India, too, has sanctioned a 50 GW PLI scheme for batteries. Central government agencies are projecting BESS installations for the grid at 27 GW by 2030.

Firms like Reliance are trying to produce cheap electrolysers. In addition, India has provisionally settled on a 5 GW target for electrolyser manufacturing by 2030 – with caveats that this might rise.

Think about it. India’s installed capacity of solar and wind is about 175 GW right now. The country wants to push renewables to 500 GW by 2030. At that level, said Shrivastava, India will “need as much as 85 GW of storage to balance the grid”.

India’s planned 96 GW of pumped hydro—and its projected 70 GW capacity comprising multipurpose dams and run of the river projects—will have to compete with newer forms of storage for this 85 GW space.

The resulting interplays are still evolving. On one hand, batteries and electrolysers are yet to be deployed at scale. On the other hand, hydel is a mature technology with little scope for dramatic cost reduction. Within hydel itself, pumped storage, run-of-the-river and multi-purpose projects come with different competitive advantages.

These two interplays—with storage, and within hydel—will determine hydel’s role in India’s emerging energy architecture.

(Next week: Can hydel take on batteries and electrolysers?)