India’s renewable energy market is booming with opportunities, but challenges in financing, regulation and scalability pose risks to its long-term sustainability

“Green stocks are for the future. It’s not good for short term investments, as of now. But it will grow,” says 55-year-old Samir Sen, who has been trading professionally for the past two decades.

While he hasn’t dipped his beak in the green energy stocks as of now, he’s been keeping a keen eye on them for the past three years, as the stock values are rising. Moreover, he’s hopeful that the stock prices will stabilise once the companies grow and scale up.

His bet lies on India’s growing appetite for power, especially during the scorching summers when power demand shot up by 15% in May 2024 to 156 billion units. Renewable energy, especially solar, can offset this peaking demand caused by overuse of air conditioners, as there is longer and more intense sunlight.

The government, too, is hedging its bets on growing this segment, with a keen eye for hitting 500 GW of renewable energy capacity by 2030. According to a report by JMK Research, India’s total renewable energy generating capacity stands at 209.44 GW as of December 2024. Installed renewables grew by nearly 28 GW in 2024. More importantly, 46.3% of the country’s total installed capacity is renewables.

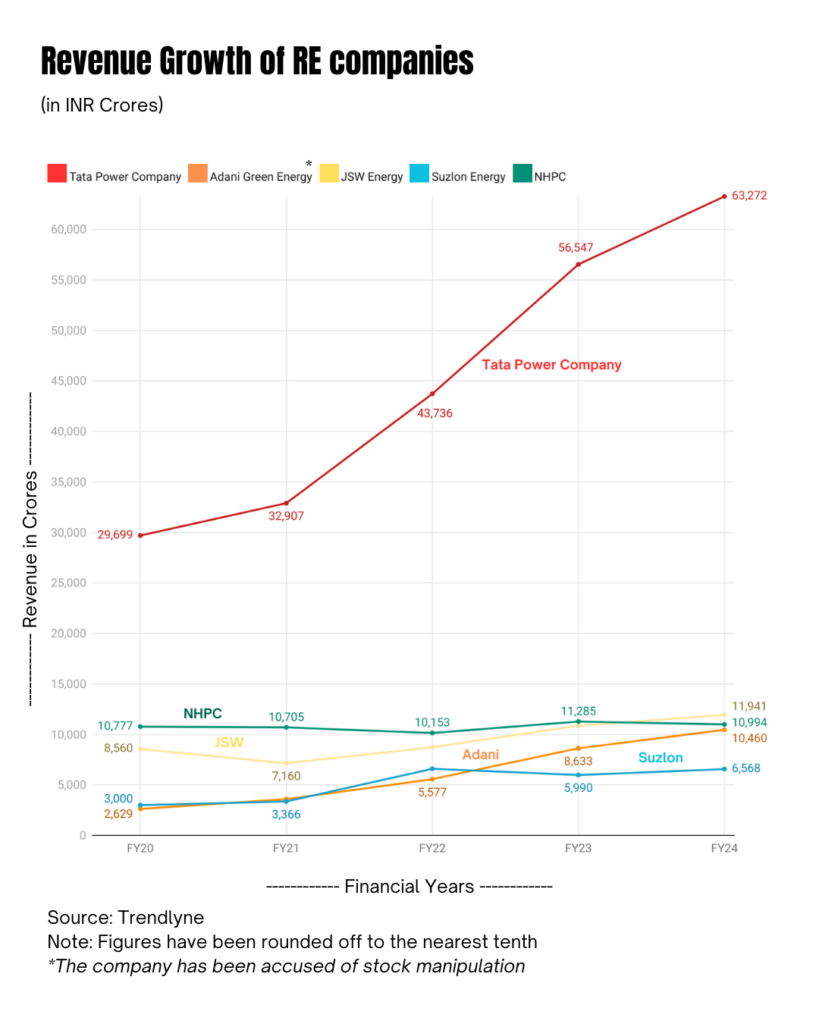

In turn, this means that companies have been growing. Some of the biggest green energy companies in India like Tata Power and JSW Energy have market capitalisations of ₹114,058 crore and ₹95,751 crore respectively, as of January 14, 2025.

Waaree Renewable Technologies – a subsidiary of the solar panel manufacturer Waaree Energies – which generates renewable power and handles engineering and construction services, had opened in the Indian stock market with share price of just ₹2.74 in 2012. The price started climbing gradually from 2022, until it hit its peak of ₹2480.50 in April 2024 – over 1200 times its listing price.

Currently, it is trading at ₹1145.95 as of January 14. The recent dip can be attributed to a bearish movement in the overall market.

In November, NTPC Green had one of the biggest IPOs in 2024, aiming to raise ₹10,000 crore, offering share prices at ₹102-108. It was oversubscribed 2.5 times. Currently, its market cap is ₹101,132 crore and it is trading close to its listing price, hitting a peak of ₹149 on December 11.

“The renewable energy market has grown and matured. Renewables are commercially viable and can stand on their own. Investment will come through sustainable financing markets, or through bank finance,” says Shantanu Srivastava, the sustainable finance and climate risk lead at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA).

For renewable energy companies to scale up, they need to invest in physical assets. For that, nearly 80-85% of the financing is through debt at the moment, so there shouldn’t be a problem raising equity now, according to Srivastava.

The renewable energy market has undoubtedly reached a stage where investors, including retail, are putting in money. Most stock prices have shot up considerably in the past few years, till the recent slowdown. The market will only get bigger with at least five more companies planning to launch IPOs in 2025 — more avenues for investors to pump in money. But that doesn’t ensure that the risks are completely eliminated. The question lies in whether the returns are trumping the risk.

Steady returns

With green energy companies growing, the returns on investment are also growing.

“The next generation of boom is in green stocks. In 5-10 years, it will be more useful. In order to get good returns, we need to buy them for a very long term for 10-15 years,” says 38-year-old Srinivas Chava, an engineer who has been actively trading since 2008. His investment in Inox Wind has rewarded him with around 30% returns.

A recent investor in green stocks, Shubham Thakur also plans to be dug in for the long haul. “Every sector that encourages green innovation and solutions for a climate-conscious economy will be at an economically advantageous position,” says the 27-year-old climate policy analyst.

In 2024, the renewable energy sector saw an influx of roughly ₹100,000 crore in total, nearly double the funds that went into traditional energy sectors like coal and refinery, according to a senior analyst with a prominent securities firm, who wished to remain anonymous.

By 2027, the investment in the renewable segment is expected to grow by 3X, while conventional energy forms will see similar investments as now.

“In relative terms, old energy sectors will decline. Once more renewables get into the system, conventional energy will decline further. It will have to,” said the analyst.

Also, some retail investors are looking to pump money in companies which have a hopeful outcome or rationale behind their technology, like green energy.

Most importantly, India’s renewable energy market itself is attractive to investors. Why?

“The performance of these projects have been pretty good. On the debt side, lenders get their money back and the credit ratings of the loans have improved over time. For foreign investors on the equity side, the runway of capacity addition is attractive, and this sector is going to see continued ability to deploy capital as pension, wealth and private equity funds are interested,” says Gagan Sidhu, director of the Center for Energy Finance, Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW).

Citing the DRHP of Indian Renewable Energy Development Agency (IREDA), a government company that finances renewable projects, before it filed its IPO in 2023, Sidhu said the non-performing assets (NPAs) were insignificant when it came to solar and wind.

Also, as the technology for renewable has matured over time, domestic financial institutions have overcome hesitancy in lending for such projects. Sidhu says that an overwhelming part of the debt for funding renewable energy projects in India have come through domestic banks and non-banking financial companies (NBFCs).

Initially, the financing of under-construction renewable energy projects is mostly done through domestic bank debt, says IEEFA’s Srivastava. “Financing from domestic funds has been increasing more than foreign banks in the past three years, especially for under construction projects. Foreign investment was subdued, except for big conglomerates like Adani and JSW, which have existing foreign financing lines. Once the project is running, it is refinanced through bond markets,” he says.

Also, for the investor, there are multiple avenues to invest. “Power, electric mobility, decarbonisation of industries, and the technologies which cater to these sectors, are potential destinations for investment,” says CEEW’s Sidhu.

He further points out that the investor has choices as to which part of the segment they can put their money in – from manufacturers like Waaree, finance lenders like IREDA to companies like NTPC Green which deploy renewable energy.

Furthermore, investment opportunities are arising in other clean technologies like battery storage and pumped hydro, while sectors which still have to take-off, like offshore wind and green hydrogen, can be potential bets for the future.

Government push

Also, the government’s clean energy ambitions are helpful. Its target setting – of achieving net zero by 2070, and 500 GW renewable capacity by 2030 – is “underrated in its ability to inspire confidence” in the market, according to Sidhu.

In the past few years, the government has emphasised on pushing renewable energy projects, with major investments flowing into wind and solar. As of December 2023, there were 10 ongoing schemes and programmes to support renewable energy, including PM-KUSUM, developing solar power parks and mega solar projects, Green Energy Corridors, and outlaying ₹ 19,744 crore for the National Green Hydrogen Mission.

In 2020, the Production Linked Incentives scheme came into place to incentivise the manufacturing of solar modules, batteries and other clean energy equipment.

Furthermore, India marketed two tranches of green bonds valued at $1 billion (₹ 80 billion) in January 2023 to speed up expansion of renewable energy projects, major infrastructure undertakings such as metro rail lines, and low-carbon hydrogen production.

With the government’s manufacturing push through the ‘Make in India’ initiative, power demand will increase massively in the next ten years. It is expected to grow at around 8% annually, giving renewable energy a chance to play its part in meeting the enormous demand.

This, in turn, will impact green stocks positively, which are expected to have a minimum compound annual growth rate of 15-20%, according to a stock broker who wished to remain anonymous.

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), investments of around $68 billion were undertaken in 2023 in India’s clean energy space, up by nearly 40% from the 2016-2020 average. Fossil fuel investment, however, grew by only 6% over the same period to reach $33 billion in 2023.

De-escalating possible risks

Over the past few months, however, share prices of green energy companies have been declining a bit, readjusting their valuations. While this might raise questions regarding a possible bubble, it is quite normal, according to an analyst at SBI Securities, who wished to remain anonymous.

“When there is large growth, valuations of companies are high, and reach bubble territory. But since these ventures are backed by good companies, there isn’t too much volatility,” they say.

According to them, there is enough institutional interest that is driving the growth of some of the green stocks, and retail investors will catch up when they see value.

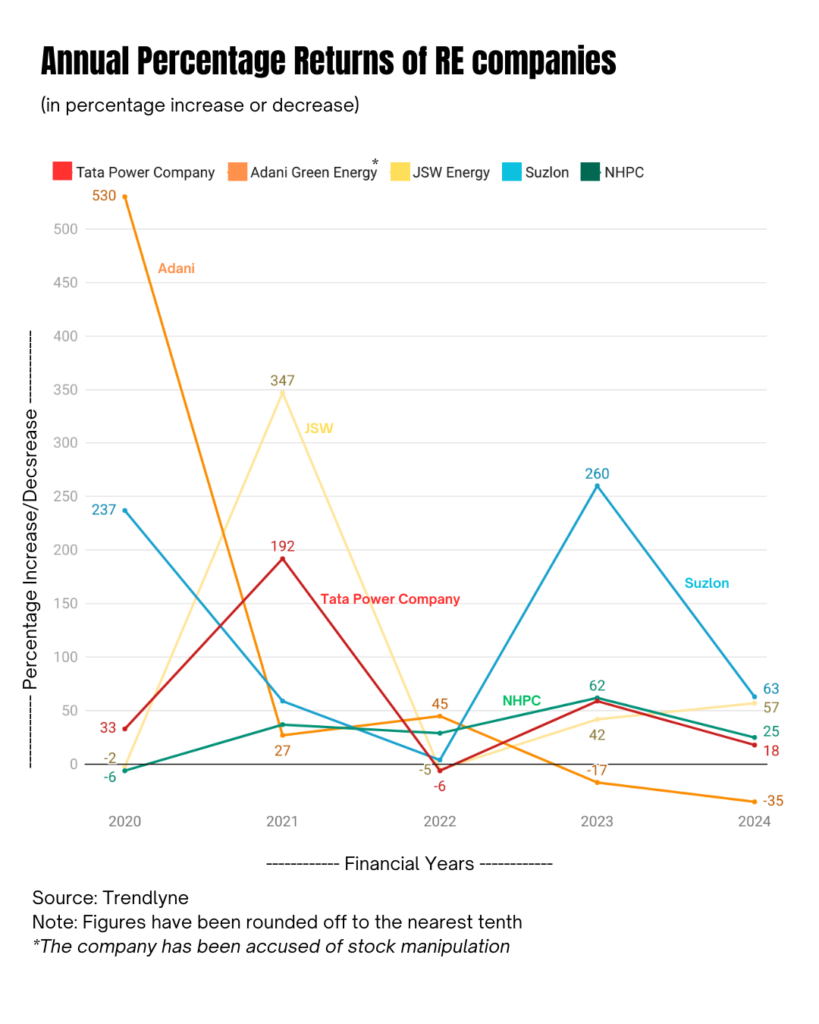

Adani Green, one of the biggest players in the game, however, is an outlier.

It listed in June 2018 with share price at ₹29.45, and grew to hit its peak of ₹2874.80 in May 2022 in just four years. In the current declining market, however, it has fallen to ₹889.75.

Besides the bear market, the sharp fall can also be attributed to the bribery charges brought against two of the company’s senior executives by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. In the past, the conglomerate has also been accused of stock manipulation by Hindenburg Research, a US based investment research firm. This poses both greater risks and rewards for potential investors. In fact, one particular investor made $1 billion in less than 100 days after investing in four Adani Group companies.

Going by current policies, clean energy investment is expected to double by 2030. But it’s not enough to meet India’s climate goals, and needs to rise by another 20%, according to the IEA.

But even though the renewables market has matured, the question remains whether domestic funds alone are sufficient to sustain it?

Just not yet, according to Ashish Fernandes, CEO of Climate Risk Horizons. His opinion is that while India has sufficient resources to generate a lot of investment, domestic investment is not as high as they should be.

“We need to be installing 40-50 GW every year to meet 2030 goals, but we installed 28 GW in 2024, just over half. While we are tendering close to the target, domestically we are raising only 50% of what we can raise,” he says.

According to him, there are two major hindrances at play here: skepticism about excessive valuations in the Indian equity market, and the lower returns of free market renewables compared to the regulated coal power sector.

“If there is doubt about the valuations of green energy companies, that could play a negative role. On the other hand, costs of electricity from conventional sources, mainly coal, are rising. So, solar and wind are clearly advantageous for common consumers and the Indian economy as a whole, but we cannot realise these benefits while coal — whose prices are regulated with guaranteed returns of 15.5% — grows and competes with renewables,” says Fernandes.

The scepticism is further fuelled by the market’s volatility and possibilities for corruption.

“We still don’t have a green taxonomy. As a result, there is too much ambiguity about what a green bond in India means. Our disclosure policies are not great – the BRSR framework has been weakened by SEBI, where mandatory disclosures regarding ESG were made voluntarily. By not having safeguards, we are sending wrong signals to investors, both in the Indian market and overseas,” says Fernandes.

During the July 2024 Budget, the Indian government had promised to introduce green taxonomy, and it is expected this year.

CEEW’s Sidhu also points out that risk perception is specific to the technology and the business model. “The newer the technology, the higher the risks. It’s simply because the cost of financing newer technology is higher than established ones,” he says.

Then, there are inherent risks like acquiring land for big renewable projects like solar parks.

At the core, risks boil down to three factors – the finance isn’t flowing, it is too expensive, or the investment is just not enough, according to Sidhu. A possible solution lies in blended finance models.

“In the case of the technology being too expensive, blended finance can lower purchase costs. If the flow of finance is not smooth, unlocking finance will work,” says Sidhu.

But the financial health of discoms is certainly a concern, according to both Sidhu and IEEFA’s Srivastava.

“At the end of the chain, it is going to be a discom which is going to be paying the bill. Being a very complex sector with different shades of financial performance, there was a clear risk perception amongst investors. To mitigate that risk, government intermediaries like SECI (Solar Energy Corporation of India) and NTPC (National Thermal Power Corporation) were utilised to execute purchase power agreements (PPAs) with discoms,” says Sidhu.

Through PPAs, discoms can purchase electricity reliably at a fixed price.

While India may be pushing on the pedal for coal, renewable energy combined with other forms of clean technology is undoubtedly the answer for a net zero future. It is growing and needs to grow more, especially if developing nations cannot rely on climate finance from the developed world.

About The Author

You may also like

Climate Talks in 2025: Converging Crises, Rising Stakes, and Diminished Returns

Converting Coal Mines to Solar Can Add up to 15% of Global Capacity: Report

Targeted co-financing can solve the challenge of just transition in emerging economies: Report

Global North Countries Responsible for 70% of Oil and Gas Expansion: Report

Can biochar be India’s missing link to carbon capture?