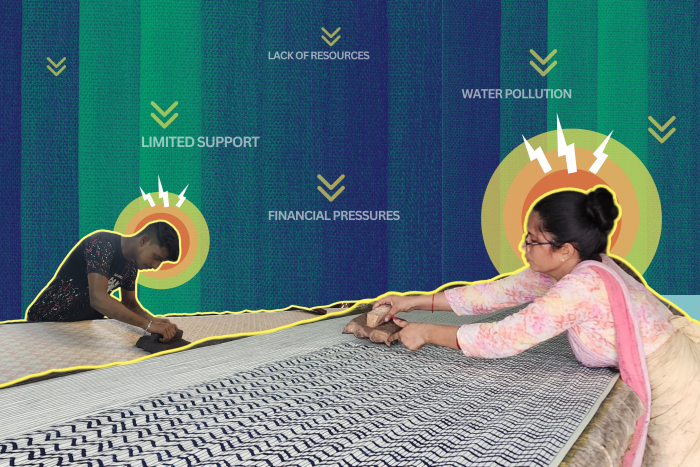

With CETP delays, water pollution crackdowns, and limited state support, the country’s oldest textile traditions are under strain—and the artisans behind them are paying the price

In the narrow lanes of Sanganer in Rajasthan, which is known for its centuries-old tradition of block printing, lie a myriad of tiny shops filled with vibrant and colourful clothes and busy block-printing units. Behind these shops lies a larger truth – a number of people working tirelessly in dingy spaces to bring these prints to life. But things were not always this busy. Around 20 years ago, many of these units were forced to shut down after synthetic dyes were found to be polluting local waterbodies and affecting livestock. The shutdowns hit the local Chhipa community—practitioners of the craft for over 500 years—particularly hard.

In a state like Rajasthan, where water is scarce and groundwater accounts for just 1.72% of the national stock, the block-printing industry’s water use in the state—up to 1,000 litres per unit per day, according to the Central Ground Water Board (CGWB) report —is no small issue. Using this figure, the scale of this consumption is staggering. With an estimated 850 dyeing and printing units in Sanganer, the textile industry consumes approximately 25.5 crore litres of water annually if they operate roughly for 300 days a year. According to the Ministry of Jal Shakti, the benchmark for urban water supply is 135 litre per capita per day (lpcd). This means that water consumed by just one printing unit in a year could meet the needs of approximately 1,293 households. Sanganer’s story mirrors wider concerns across India’s textile belts, where the push for sustainability is now closely woven to the question of survival—for both its workers and the environment.

India’s textile industry represents not just the country’s rich cultural legacy, it also serves as an economic lifeline. According to Invest India, the Indian textile and apparel industry is currently valued at approximately $174 billion and is expected to reach $350 billion by 2030. It is also one of the largest employers in the country, second only to farming, directly employing over 45 million people. The downside, however, is its footprint in the form of water use and pollution.

In June 2025, the Ministry of Textiles released a draft roadmap for 2047, which looks into building a sustainable, circular, and resource-efficient industry. This roadmap was announced after speaking to stakeholders, including the ministry’s ESG Task Force. Textile Secretary Neelam Shami Rao mentioned efforts taken in textile hubs like Surat, Tiruppur, and Panipat, ranging from wastewater recycling to renewable energy use and waste management that need to be scaled nationwide. A good start, but how this will be implemented across the country is still to be seen.

“The government needed to come up with a solution that not only looks at the environment, but also at the community relying on it,” says Vikram Joshi, who runs Rangotri Foundation, Rajasthan-based hand-block design studio.

The road ahead is riddled with tough questions. Who will bear the cost? Are traditional artisans getting the support they need to adapt? Can stringent green norms coexist with economic survival? And can India strive to make its textile industry more sustainable without leaving its workers behind? As CarbonCopy found while working on this report, the costs of sustainability are falling heaviest on the artisanal units in the textile supply chain.

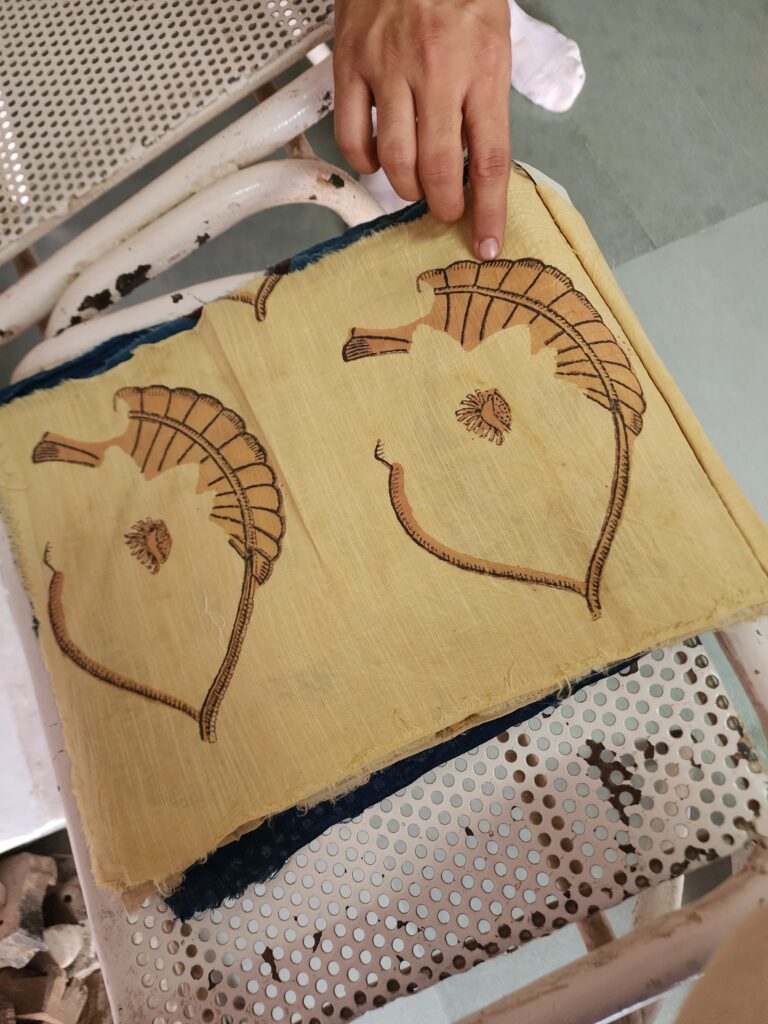

Before the dyeing process begins, the cloth is cleansed and treated. Photo: Paridhi Choudhary

The CETP Dilemma

In Sanganer, the area surrounding the Dravyavati river, extending for miles, is dominated by dyeing units. This river serves multiple purposes. It is used for harvesting water chestnuts, washing clothes, and providing drinking water for cattle. Yet, despite the vital role the river plays in sustaining livelihoods, it also bears the burden of untreated industrial waste.

Common Effluent Treatment Plant (CETP) facilities were set up in nearly every unit over two decades ago, but much of the wastewater still fails to reach the city’s lone treatment plant in the west. The infrastructure exists on paper — but not always in practice.

CETP plants were intended to treat and recover 80% of textile process wastewater, returning it to the system for reuse in dyeing, printing, and washing clothes. Furthermore, each unit is mandated to install individual effluent plants to maximise water recycling.

A nationwide report by the Central Pollution Control Board found that out of 191 CETP plants across India, only 128 were complying with norms, while 63 of them were non-compliant and another 84 units were under construction. A majority of these non-compliant CETP units are located in Gujarat, Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu, and Delhi.

Following the ban, dyers formed an association to collectively manage the costs of these CETP plants and navigate bureaucratic obstacles. Despite their efforts like providing a platform for the dyers to have a voice in the new regulations, challenges persist. Mohammad Salim, another dyer in the area, commented, “The government often cracks down on the dyers for the discharge of chemical water and this often affects our businesses.”

Salim explained that while their units treat wastewater, the primary challenge lies in the absence of a proper system to transport this water to the main treatment plant. He stated, “Currently, we are sending the water from our units in tankers, but this is not enough considering the amount of water used in processing the clothes, and the rest of the water ends up reaching the river.”

Baverwal says, “The main CETP unit that has been set up in the city can only accommodate wastewater from up to 400 units, but the total registered units in place are around 850.” He also mentioned that, due to the absence of a CETP, every dyer was required to pay ₹500 per month for the ETP set up in each unit.

Challenges for Salim and Baverwal still persist even after being registered as a part of the association of dyers in the area. They said that they paid a one-time fee of around ₹7.5 lakh. This fee has now gone up to ₹15 lakh. Many dyers in Sanganer can hardly afford this amount. Last year, a joint committee report on pollution of riverbodies in Rajasthan shut down 29 illegally operating textile units in the area.

In 2023, the National Green Tribunal (NGT) directed the state of Rajasthan to pay compensation of ₹100 crore for the damage to the environment caused by the textile printing unit in Jaipur. The bench at the time noted that the Dravyavati Restoration Project costing around ₹1,676.93 crore did not mention any formulation and execution of an action plan for the critically polluted area of Sanganer.

The green panel also gave liberty to recover this amount from units that have violated the norms. The bench also ordered that the CETP unit should be made operational, which has been in place since 2019. They also ruled that no new unit should open in the area till adequate infrastructure is in place.

But making CETPs work is easier said than done. A report by ScienceDirect highlighted the operational and technological challenges for CETPs across India, including outdated equipment, effluent quality, and lack of skilled labour. Without addressing these systemic issues, enforcement alone may not lead to meaningful clean-up, say experts.

“There is little left for us after paying rent and the fees for CETP,” says Hariom Baverwal, a dyer in Sanganer. Like him, many small-scale operators often bear the brunt of sustainability costs.

A shift to faster printing

The cost of compliance is not limited to dyers. Block printers and handloom workers, too, face rising costs, declining sales, and growing competition. Hand-block printing, an artisanal, time-consuming, and labour-intensive technique, faces competition from screen printing, an easier and more efficient method that gained popularity in the early 2000s, along with machine-made printing.

Competition from bigger brands has also forced the Chhipa community to take smaller orders and even shift to screen printing as the work remains labour-intensive and is set up in dingy places.

“I grew up learning the craft, but left it within a year and started working at a screen printing unit. Here the work is less labour-intensive than block printing and margins are much better.,” says Dinesh Marwal, one such artisan from Sanganer.

The numbers reflect the shift. Screen printing can produce up to 500 metres of printing cloth in a day, while block printing can only produce up to 100 metres. But the environmental cost is high. The green tribunal has repeatedly mentioned water discharges from screen printing in its orders, which are often dumped in pits and potholes outside these units. However, unlike dyeing units, screen printing units remain largely unregulated.

Adding to the pressure is the broader textile economy. Fast fashion brands and online sellers frequently release new designs and patterns, making it tough for traditional artisans to keep pace. With states like Maharashtra, Gujarat, and Tamil Nadu quickly becoming hubs for mass production of machine-made textiles, the ground is shifting fast.

A missing support system

Himanshi Singh, who is a founding member at Bare Craft Consulting, a Delhi-based platform to bridge the gap between rural artisans and global small-medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) across India, says, “Most of the artisans at small scale struggle because most of the regulatory changes are often made for large-scale industry, not handloom or cottage industries, creating confusion.”

Singh adds that unless artisans are financially and technically supported, imposing compliance can crush livelihoods, especially in rural places.

Rohit Rusia, founder of ASHA, an organisation working to revive handblock printing in Madhya Pradesh, said they have been working along with the women in Chhindwara district in the state, and they make water for pigment from vegetables. ASHA now sells their products across the country without any middlemen or brands to provide a minimum sustainable income starting from ₹12,000-₹13,000 per month to their artisans.

He says, “Unlike Rajasthan, we did not get any state support to revive the industry, and after the cancellation of contracts from Madhya Pradesh emporium, many artists here are struggling to sustain.”

Until recently, many artisans relied on government emporiums and Tribes India stores to sell their products under the Ministry of Welfare of India. However, these institutions are now plagued with challenges such as delayed payments and diminishing sales. The state emporiums have now stopped accepting their work, artisans say.

“Products that are available through government emporia [state or central] have deteriorated in quality and workmanship, because of both these issues, and because of a lack of a skill and quality mindset within the government framework. All of these mean that the multi-generational chain of craft and skill gets broken due to unfavourable economic and regulatory conditions,” says Devangshu Dutta, founder, Third Eyesight.

This erosion is playing out on the ground in Sanganer. Most artisans here said the profit margins have reduced over the years and the clientele is also dwindling.

While the lack of institutional support continues to undermine artisans across regions, those trying to stick to sustainable practices like natural dyeing face an additional layer of financial and operational hardship.

The Cost and Complexity of Sustainable Dyeing

Bagru, a village 30 kms south of Sanganer, houses some of the few block printing units that still work with natural dyes. These dyes are environmentally friendly because water discharged from them can be reused directly for farming and feeding livestock without the need for effluent treatment. One such artisan is Sunil Narain Titanwala. He shifted to Bagru from Sanganer about 40 years ago and started his unit here in the village. Unlike his counterparts in Sanganer, he continued to use vegetable dyes for dyeing and block printing.

He has worked with many brands in India and abroad, including Anokhi, with whom he has had a working relationship for more than two decades. He says that even though there are many opportunities coming his way, he struggles to keep up because of a persistent labour shortage in his unit. “I don’t have enough money to hire more labour because at the end of the month, I am left with ₹20,000-30,000 in hand. I have to also look at the household expenses and water and electricity bills in that money.”

He says many workers from the Chhipa community, who once ran traditional craft shops in the village, have now turned to selling machine-made clothing.

Prahlad Dosaya, another natural dyer in the village Dosaya has also been working with Anokhi and has about 130 people working with him.

Shubham Dosaya, Dosaya’s 21-year-old grandson, who manages the unit along with his grandfather, says, “We have a lot of demand coming our way, but the major problem we face is time constraints. We cannot work during the monsoon season because we cannot dry the dyed clothes outside.”

He adds that the hand-block industry, especially when relying on natural dyes, is not profitable. The price of their work is dependent on the kind of designs they are making. He says, “For every metre of cloth we sell, we earn ₹150, and the profit margin is around ₹6.”

Before and After: The design undergoes a month-long process before it can be transformed into reality through natural dyeing. Photos: Paridhi Choudhary.

Brands and margins

Anokhi, which was founded by John and Faith Singh in 1970, committed to provide sustained work to artisans throughout the year. It has 25 shops across India and 8 international stores, which sell products ranging from clothing to furnishings.

On the use of natural dyes and sustainability, Singh says, “We collect and recycle water. This does not supply all of our water needs, but we are able to collect a substantial amount of rainwater across several very large reservoirs, which replenish throughout the monsoon and last for several months after. We recycle our printing effluent and are able to reuse that for the staff bathroom in the factory, amongst other things.” She adds, “Our natural dye percentage is almost 20% in our shops, and we are continuously trying to increase the percentage for natural dye.”

“We create items [clothes] where we can remain price-sensitive and make a decent margin”, says Rachel Singh, Director, Anokhi. “ Those items support other products we create where we continue to be price-sensitive, but can only make very little margin because the costs are greater. “ The year-on-year revenue of Anokhi for fiscal 2024 was ₹153 crore as per their MCA filings under the name of Gangaur Exports Private Limited.

There are also many export houses on the outskirts of Jaipur, which source from a cluster of producers. They are all situated in a new industrial area created called Jaipur Integrated Textcraft Park. They have an in-house effluent treatment plant and rainwater harvesting. Joshi from Rangotri Foundation says, “Although we still use synthetic dye for printing, we have set up an in-house treatment plant for sustainability.” He said that their annual turnover comes to around ₹12 crore.

But the margins tell a different story when viewed from the artisan’s end. For example, a kurta at a high-end sustainable label with an indigo block print design costs around ₹3,550. The cloth length of this kurta is 85cm. A natural dyer that CarbonCopy met said they would sell the same cloth for ₹375 per metre.

On top of this, many brands have patented every design, leaving artisans with no rights over them. They send artisans designs they want them to create, and sharing or mimicking these designs could cost them their wages.

Questions around authenticity remain. “True supply chain transparency is followed by very few brands. Large brands can and do get away with greenwashing on a global scale, not just in India – by certifying a very small fraction of their product as water-friendly or carbon-friendly, large brands that are otherwise pushing disposable fashion get to pretend that they are green,” says Dutta.

A report by Access Development Service, which works on sustainable development goals through grassroots partnerships, highlighted that the handloom sector continues to face myriad challenges like weak implementation of protective regulation, limited consumer awareness about India’s diverse textile traditions and the undervaluation of handloom products.

The road ahead

For artisans like Titanwala and Dosaya, demand for natural-dyed clothing is rising, but so are the barriers to scale. Without financial backing, even sustainable production becomes unsustainable.

As Himanshi Singh pointed out, big brands have the resources to shape the sustainability narrative. But for small-scale artisans, especially in rural India, sustainability isn’t a buzzword, it’s a daily calculation of how to preserve tradition, protect the environment, and still make a living.

To truly save the traditional handloom industry, promotion of natural dyes must be scaled up with modernisation of CETPs, stricter environmental monitoring, and financial aid for small dyeing units, especially in handloom-rich areas, says Himanshi Singh. A cluster-based community led model, backed by government subsidies, private partnerships, and green technology is the way ahead to preserve the craft.

The handloom industry remains the second-largest employer in rural India after agriculture. Without fair pricing, adequate infrastructure, and targeted policies, this thread of India’s cultural and economic fabric risks being slowly unspooled.