Investing in women’s health, education, and social security is crucial to achieve gender equality in a just transition, say experts

For many women in Dhanbad, the day starts before dawn as they set out on foot to their neighbourhood coal mine. Their job is to carry lumps of coal back from the mine’s depot yard to their male co-workers waiting outside the mine.

Their job comes with extreme risk. It involves unending repetitions of filling their metal bowls with coal, adjusting it on their heads, carrying it back outside, and emptying it for the men to take forward. With each iteration, they emerge from the mines darker, covered in a fresh layer of coal dust–which ironically is perhaps the closest thing to a certificate they will get for the gruelling work. The men then pack the coal in plastic bags and set out on their bicycles to sell to roadside restaurants and coal brokers.

This cycle of labour is not limited to Dhanbad, and is, in fact, typical for many coal-bearing regions in India. “Coal-peddling” is a family operation and the division of labour is transparent. The role of women in this whole process is crucial since only they enter the depot while men limit their roles to outside the mine. Payment, however, is typically reserved as a male privilege.

Interestingly, the clear disparities in working conditions and remuneration fall contrary to the value of work added by women in the coal-peddling value chain. If women didn’t bring the coal, men would have nothing to sell. A study noted that even if the male in the house is unable to push a cycle, the women still generate income from coal on their own.

In its truest form, the concept of just transition seeks to move towards undoing injustices that have become systemic in India’s growth story, particularly in the energy sector. As the concept enters the mainstream discussion in India, it is crucial to ask whether this will be an opportunity for women or if it is doomed to follow the same structural patterns that have demonstrably suppressed their voices.

How will just transition be different for women?

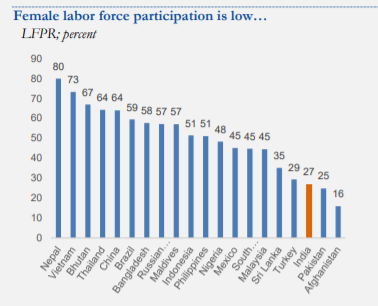

According to World Bank’s estimates, India has one of the lowest female labour force participation rates in the world, even lower than its neighboring countries Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Nepal.

There are also regional differences, with states such as Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, Delhi, and Bihar showing much lower participation of women in the workforce.

The same trajectory can be seen in coal mines where men comprise a majority of the workforce (98.4%). In law, the precedent was set by the Mines Act of 1952, which prohibited the employment of women in underground mines and allowed them to work only in above-ground mines. While the law has been amended to allow women to work in underground mines during daytime, they can only occupy “technical, supervisory and managerial” positions.

Sreshta Banerjee, director of Just Transition, at iFOREST, said there is generally very little women participation in the extractive industry. Talking about Jharkhand, she said a majority of women who are engaged in the coal industry are part of the informal workforce.

“There is a variety of work in the informal workforce, but women are employed in the lowest form, which is coal gathering,” she told CarbonCopy.

Speaking about women’s workforce in India, Ulka Kelkar, director of the climate programme at the World Resource Institute (WRI), said jobs for women in India tend to be highly informal, lacking safety nets and good working conditions. Moreover, women’s wages are often much lower on average than that of men.

During last year’s COVID-enforced lockdowns, women’s employment was hit first and harder, and it took longer to recover, even in developed economies. A recent government report revealed that in the July-September 2020 quarter, the female labour participation rate fell to 16.1% — the lowest among the major economies reflecting the effect of the pandemic and the broadening job crisis.

Statistically, women tend to be employed more in specific sectors such as the garment industry, domestic help, agriculture, and services. Even within a sector like agriculture, women are employed on more manual jobs, like weeding, while men’s jobs involve the use of machines and access to markets.

“When certain industries expand, like the auto industry, women often lack the skills to access the new job opportunities. They also lack the documentation and collateral to get loans to set up small businesses,” Kelkar said.

According to her, existing gender imbalances and inequalities will continue even as India shifts to a low-carbon economy unless the country makes special efforts for skilling women to access good quality jobs in renewable energy, electric mobility, and green buildings.

(Unpaid) care work

As with other sectors, the primary responsibility of (unpaid) care work for children and elders tends to fall on women. As a result, they are either not able to take up job opportunities, or are compelled to switch to part-time work or drop out.

The World Bank report also regarded this as one of the reasons for the falling female workforce in India. It said that there is overall limited creation of jobs in the country that ends up being taken by men due to social norms and other gender-specific constraints. Considering the social norms that require women to reconcile work with household duties, other challenges weigh in like safety, flexibility, availability of childcare, and adequate pay.

Speaking about low-carbon jobs, which will come up as India transitions away from fossil, Kelkar said it is very likely that new low-carbon jobs will come up in different locations than conventional jobs and women might find it difficult to relocate to take advantage of these opportunities.

Does transition present an opportunity for women?

While some experts believe that just transition is going to be an opportunity for women, others are sceptical about it. Just transition can provide a platform to talk about gender equity within the ambit of the imminent transition to low-carbon development, rather than re-examining the process at a later stage. However, making assumptions about women’s aspirations while planning the policy rather than involving them will not undo the historical injustice.

It will not be different for women if it is not imagined differently, said Shweta Narayan, global climate & health campaigner at Health Care Without Harm. “Just look at all historical planning processes. Women are an afterthought, even though they have the highest stake and they are the most affected from a social, environment and health perspective. Unfortunately, policies are not designed keeping women in mind,” she added.

The process of low-carbon transition, however, also offers the greatest potential for benefits to women, according to Rathin Roy, the managing director of research and policy at the Overseas Development Institute. Roy said a low-carbon transition will benefit women as they are the ones who face the larger brunt of a high-carbon pathway, provided appropriate community interests motivate the transition.

“If women are excluded from just transition then it is less likely to happen,” he said.

Do industries prefer male workers?

To add to this, employers have a historical predisposition towards hiring male labour. An enterprise survey taken by the World Bank in Madhya Pradesh revealed that if jobs are scarce, men will have a greater right to a job than women. When asked whether men made better employees than women, 42% of the respondents agreed, while 30% did not have a view and the remaining 28% disagreed. Another survey conducted by Pew Research found 84% of Indians agree with the statement “when jobs are scarce, men should have more right to a job than women.”

“Women are the first to lose a job whenever there is a shortage and they are the last to get a job,” said Rahul Tongia, senior fellow with Centre for Social and Economic Progress (CSEP). If a mine closes in a region and some new economic activities come back over time, the first to take up the jobs will be men due to cultural as well as other reasons, he said.

If there is an economic downturn due to fewer jobs, women will be hit the hardest because they have to take care of the family, look after food and water, which takes a lot of effort, he added. If there is less money, they are not going to use LPG and will be stuck with traditional methods that are time and labor-intensive as well as have a severe effect on their health, he explained.

How to achieve gender equality in just transition?

In a patriarchal society, the shouldering of household responsibility falls on women due to which they have to bear the indirect economic costs in terms of missed opportunities for employment, leisure, and education.

One of the significant ways to achieve gender equality in a just transition is to invest in areas crucial for gender parity — health, education, and social security. The inclusion of re-training initiatives, compensation schemes, and social protection arrangements in the just transition narrative will likely be essential for any improvement in the equitability of the gender-based power dynamics in India’s society.

For new low-carbon jobs, skilling programmes will have to be provided at convenient times and locations for women to be able to participate, said Kelkar from WRI. The workplace should provide safe transport, sanitation facilities, and creche, she stressed.

Married women may have limited ability to migrate for work, she said, but young unmarried women could be provided hostel facilities. In addition to jobs, there is also an acute need to enhance access to finance for women entrepreneurs, who can set up small rural enterprises run on renewable energy, she emphasised.

Renewable energy can pave a path to ease women’s domestic and care-burden. Women living in poor and economically vulnerable societies are dependent on biomass for cooking, lighting, and heating. As natural resources get further depleted and biomass becomes harder to find, more time and energy is spent covering longer distances to collect fuel for themselves. In a just transition, providing easy access to renewable energy can have a positive impact on women’s rights and at the same time help combat climate change. It will curtail time spent on household chores, enabling more flexibility in sequencing tasks.

During a focused group discussion with women in Jharkhand, Banerjee from iForest learned that women workers fear that if the informal workforce is not absorbed in the organised sector, work will once again shift to households. This, they are afraid will worsen problems of alcoholism and domestic abuse, Bannerjee said.

She believes that a just transition is definitely about participation and decision-making, but it is more about what kind of job is being created and how secure these jobs are otherwise “you end up in the same loop.”

According to her, it is women’s security in employment that will determine how the gender component is really factored into the application of the just transition concept. She further stated that education can play a significant role in empowering women.

This is the third and the final installment in a three-part series on the prospects of a just transition in India’s coal belt. You can read the first two articles here:

Profound inequality bears heavy on India’s energy transition

Pitfalls and opportunities: How to find justice in India’s low-carbon energy transition

About The Author

You may also like

Loss and Damage Fund board meets to decide on key issues, Philippines chosen the host

9 years after launch, India’s solar skill training scheme yet to find its place in the sun

India’s new hydel push can’t turn blind eye to Teesta III failures

Teesta disaster: How not to build a dam

Shut down, shut out: Closure of Badarpur thermal power plant a lesson in “unjust” transition