The country needs to decarbonise. Its renewables face charges of intermittency. Is nuclear the answer?

On December 14 last year, Union minister of state for Atomic Energy and Space Jitendra Singh made an announcement with far-reaching consequences.

In a written reply to the Lok Sabha, Singh said the BJP-led NDA government will commission 20 new nuclear reactors by 2031. With that, he said, India’s installed nuclear capacity will treble from the current 7,480 MW to 22,480 MW.

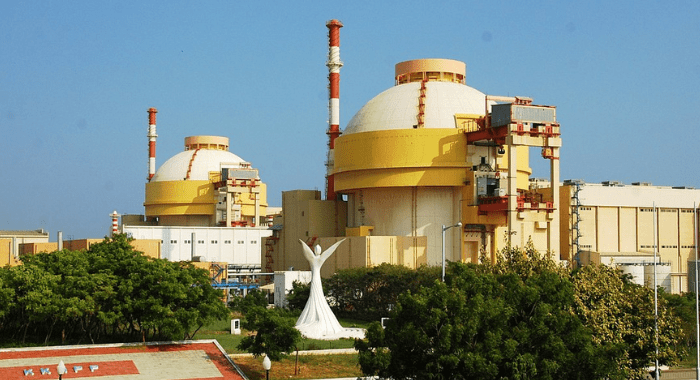

Ten of these reactors—like the 500 MW Prototype Fast Breeder Reactor at Kalpakkam and the two 1,000 MW reactors at Kudankulam—are already under construction. In addition, the government has granted “administrative and financial sanctions” for building 10 more nuclear plants with 700 MW Pressurised Heavy Water Reactors at Gorakhpur (Haryana), Kaiga (Karnataka), Chutka (Madhya Pradesh) and Mahi Banswara (Rajasthan).

That is just the start. Another clutch of reactors have secured in-principle approvals. Once all these projects are up, the number of India’s nuclear reactors will rise from the current 22 to well above 50.

(Source: World Nuclear Association, Times of India, Press Information Bureau, India Nuclear Business Platform)

That is not all. The NDA government is also bullish on SMRs, typically below 300 MW in capacity, and wants to use them for both power generation and to decarbonise industry. National Thermal Power Corporation (NTPC) is thinking of retro-fitting small modular reactors (SMRs) into decommissioned coal plants. In August, speaking at a conclave on green hydrogen and net zero, senior Niti Aayog official VK Saraswat said industrial units too should use SMRs to produce hydrogen.

Some of the projected numbers are mind-boggling. The installed capacity of coal-fired plants in India stands around 220 GW. “[Of this 220 GW], 20 GW is already off the grid and gradually others will also be coming in the line,” AK Nayak, head (Nuclear Control and Program Wing) at the Department of Atomic Energy said last December at a conference organised by India Nuclear Business Platform, a nuclear power advocacy firm owned by a Singapore-based consultancy called Industry Platform.

These, he said, can be refitted with SMRs. “There is a big opportunity for SMRs in a span of 2-3 decades… For interested companies like NTPC and others it is a business opportunity of 220 GW.”

Going by such projections, SMRs might play a bigger role in India than large reactors.

The case for nuclear

A curious silence has accompanied most of these plans. Barring the odd media report outlining the government’s plans for nuclear power and op-eds in favour of SMRs, there has not been enough critical discussion around this proposed nuclear buildup.

Can nuclear energy help India step away from coal? Has the industry resolved its old problems with cost- and time-overruns? What about public safety? Given the world continues to innovate in renewables, should India go for 100% renewables or push to add nuclear capacity as well?

On the energy front, the country is stuck between a rock and a hard place. In 2022-23, its power demand stood at 1,503 billion units (BUs). This demand was met through an installed power generation capacity of 415.4 GW, with 236.68 GW coming from coal, lignite and gas. Renewables—hydel, solar, bio-energy, wind and pumped storage—accounted for 171.8 GW.

As India decarbonises, not only will most of these thermal units be wound down, the country will also see additional demand for electricity as other users of hydrocarbons—like factories and vehicles—electrify as well. By 2030, India’s Central Electricity Authority expects the country’s electricity demand to touch 2,279 BU. By 2050, says Energy Monitor, power demand might touch 5,921 BUs. At this point, the country might need as much as 4,000 GW of installed capacity̦—almost a 10-fold jump from today.

That is where a massive constraint asserts itself. India’s potential RE capacity—between hydel, solar and wind—is currently estimated at no more than 1,000 GW.

It gets worse. The country cannot build to full potential capacity—building 145,000 MW of dams will extract its own social and ecological costs. As will unfettered expansion of solar parks and wind farms. India can reduce total future power demand—by slashing transmission and distribution losses or by providing Indians lower per capita power than the global average by embracing greater energy efficiency—but there will still be a shortfall.

One morning in April, seeking to understand all this better, CarbonCopy met nuclear scientist Ravi Grover at his office in Mumbai’s Bhabha Atomic Research Centre. Given the size of its population, he said in that chat, India will have to use all the energy options with her.

That morning, Grover outlined another reason why India needs nuclear power. In the past, power supply was constant (thanks to thermal power plants) while demand waxed and waned. “Balance between supply and demand was usually maintained through load-shedding,” he told CarbonCopy.

That is changing now, he said. As the share of renewables in India’s energy mix rises, both supply and demand will become variable. The country’s electricity system will need additional investments—pumped storage, battery storage, electrolysers, what have you—to balance demand and supply.

Delivering what Grover describes in Current Science as “firm power”, nuclear power can also help address intermittency. “If India wants 200 GW of renewable power, then we should try to have 20-40 GW of nuclear as well,” he told CarbonCopy. “That is what the world is doing. The UK will be 25% nuclear by the middle of this century. France is adding 8-14 new reactors. India, too, needs to add 3-4 times as much nuclear capacity. What we have is not enough.”

There is, however, one big problem.

Broken promises

This is not the first time India has mapped out a large buildup of nuclear capacity.

In the past, too, variably citing military security, energy security and looming energy shortages, India’s nuclear establishment has pushed for rapid expansion of the country’s nuclear power capacity.

In 1954, Homi Bhabha, the founder of India’s nuclear program, said India would have 8,000 MW of nuclear capacity by 1980. In 1960, the country was told it would have 43,500 MW by 2000. In 1984, a decade after the 1974 nuclear test, the country was promised 10,000 MW by 2000. The actual installed capacity was about 600 MW in 1980 and 2,720 MW in 2000.

In 1999, India’s nuclear establishment said the country would have 20,000 MW by 2020. In the early 2000s, the DAE (Department of Atomic Energy) upped that target to 275 GW by 2052—and then to 470 GW after the US-India nuclear deal. India missed those targets as well. Today, the country’s installed nuclear capacity stands at 7,480 MW.

A clutch of factors are responsible for this under-delivery. Some are global. India’s nuclear tests left the country struggling to source technology and nuclear fuels. In more recent years, the Nuclear Liability Act has dissuaded foreign nuclear suppliers from entering the market.

Others are local. As physicist MV Ramana wrote in The Power of Promise, his 2012 book on India’s nuclear power aspirations, lack of scale has been a problem. “The problem was not that the industry lacked the technological base needed to carry out the fabrication [of the reactors], but that the few orders that it received from the DAE did not make it economical for companies to do so.” Land acquisition has been another bugbear. Design changes during construction are yet another. In all, as Ramana wrote, India’s nuclear plants have been plagued by cost- and time-overruns, and performed worse than envisaged.

This is where things get interesting.

Stepping around past glitches

To ensure the latest nuclear buildup doesn’t meet the fate of its predecessors, the BJP-led NDA government has made two changes.

First, Nuclear Power Corporation of India (NPCIL) has been told to jointly develop nuclear plants with firms like NTPC. The rationale? Not only can NTPC raise funds more easily than NPCIL, by pooling their strengths in project management and nuclear plant design, NPCIL and NTPC can set up nuclear plants faster. This point was made at the India Nuclear Business Platform conference last December. “Earlier NPCIL was executing one or two projects at a time, but now with capacity getting ramped up substantially, the plan is that NPCIL along with NTPC will be running at least 10 nuclear projects at a time,” said R Sharan, director (Projects), NPCIL.

Second, seeking to obviate risks like time/cost overruns and the difficulty of land acquisition, the NDA is bullish on SMRs.

In tandem, it is also getting easier for India to source nuclear technology from outside. As nuclear energy tries to regain ground lost to renewables, a bevy of large reactor makers and SMR manufacturers are competing to crack markets like India. Anyone trying to understand the role of nuclear in India’s emerging energy mix has to engage with these shifts in policy.

Two questions, therefore, arise. Both the NPCIL-NTPC alliance and SMRs are untested experiments. Can they deliver? Further, the competitive landscape for nuclear power is changing. It no longer competes with coal and gas. Instead, billions are being spent to boost efficiency of existing renewable technologies like solar panels, wind turbines, rechargeable batteries and develop newer sources of renewable power like electrolysers. Countries are also experimenting with technologies like pumped storage and grid management to create 100% renewable grids.

So can SMRs—and NTPC—carve out a perch for nuclear power in India?

The second part of series will look into this question.

About The Author

You may also like

India’s Budget 2024-25 focuses on capacity building to fight climate change, but lacks details

Study finds that extreme weather events do not draw political attention

India’s EV revolution: Are e-rickshaws leading the charge or stalling it?

Hope for 1 lakh trees: Karnataka refuses to handover Sandur forest for mining

Stalemate over new amount: Bonn talks hit climate finance roadblock ahead of Baku summit