Government afforestation schemes, which are often in direct conflict with rights of forest-dwellers, increase the overall climate risk that India faces

Deep inside the forests of the 1,411 sq.km Sathyamangalam Wildlife Sanctuary and Tiger Reserve is the village of Uganiyam. The reserve is part of the Nilgiris Biosphere reserve and home to nearly a hundred tigers and many hundreds of elephants and other wildlife. About 100 families of the indigenous Oorali tribe call Uganiyam home. With the nearest bus stop and ration shop a seven kilometre walk and the nearest hospital 12km away on a bumpy road, life in Uganiyam is far from easy. For the Oorali people, who have always been at the mercy of the state forest department, the Forest Rights Act (FRA), 2006, was the first large-scale positive state intervention that they had seen in their lifetime.

“The only way to make our lives better is the FRA. Without that it’s hard,” said J Raman, 60, who was the village headman when this journalist had visited the village in 2017. Raman, a short, frail man, who looked worn out by years of hard work, added, “If the Act comes, we’ll get everything we need and collect what we want from our forest. As of now, if we go to get firewood or even collect gooseberry or some root vegetables, the forest department gives us trouble.”

FRA: Boon or bane?

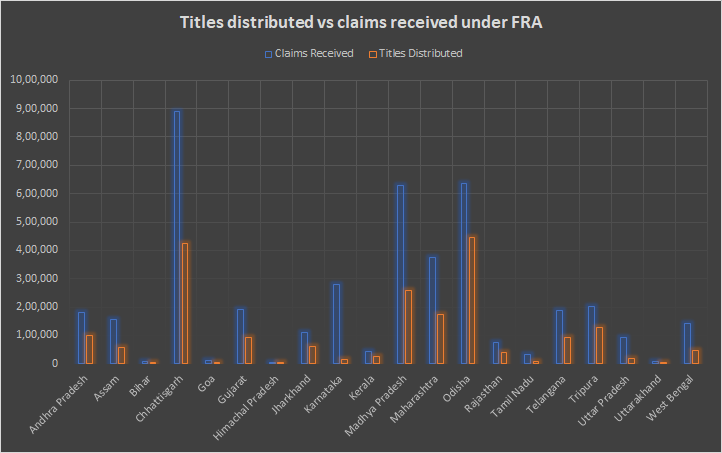

The FRA was enacted to correct ‘historical injustices’ committed against forest dwellers in India. It is also an attempt to improve the lives and livelihood of the Adivasi people, who are among the poorest of the poor in India. Since its implementation in 2008, 42,51,545 claims have been filed under the law. Out of this, more than 41 lakh are for individual claims and the remaining claims ask for community rights. Out of this, 19,07,126 individual and 76,378 community rights claims have been distributed. Nearly 50,000 hectares of land have been distributed through the provisions of the FRA. The state of Odisha has distributed 4,37,718 FRA titles, the maximum number among any state in India. The state of Goa has distributed the least, with only 25 titles being awarded. Most of the other states fall in between these two rather far away extremes. Sadly, many states tend to distribute fewer titles than they should have probably given in the 12 years since the law was implemented.

The reason for low numbers of FRA title distribution is manifold. Combined with unwillingness of state authorities to act on FRA claims, the law unfortunately has also run into a variety of hurdles, especially with regards to its implementation. Forest departments across the country, who have been accustomed to large-scale control of the forests, have been reluctant to part with their power. Recently enacted afforestation policies, such as the Compensatory Afforestation Fund Act (CAFA), 2016, are also in direct conflict with the FRA, threatening the little rights that forest communities have managed to acquire in the past decade. Combined with the impacts of extreme weather and climate-induced hazards, which disproportionately affects forest communities, it has positioned millions of forest dependent people in the middle of a double-squeeze from these powerful natural and anthropogenic forces.

Poorly conceived afforestation strategies

As per the Paris Agreement of 2015, India has pledged to bring at least 33% of its total area under green cover by the year 2030. A significant portion of this green cover is being created through provisions of Acts such as the CAFA. Apart from compensatory afforestation, the government also carries out afforestation activities through state afforestation schemes as well as through REDD+, an international mechanism developed for afforestation on a global scale to increase carbon sinks. Both conservationists and forest rights activists have taken exception to afforestation by CAFA and associated state schemes especially, stating that most of these newly created ‘forests’ are in fact only plantations and in many cases, the afforestation activities are taking place without the consent of forest-dwelling communities, who have been awarded rights under the FRA.

As Kanchi Kohli, legal researcher at the Centre for Policy Research (CPR), New Delhi, says, “The afforestation experience in India is characterised by ecological blindness, social injustices, legal irregularities and policy failures. There is enough evidence today to show that the afforestation activities have promoted mono-cultures and have not been conscious that not all ecosystems can support all species.” Kohli said that both compensatory and government-driven afforestation programmes have also been directly in conflict with prevailing rights of use of tribal and other forest dwelling communities.

The lack of consent from gram sabhas and forest departments’ pursual of afforestation projects without getting their consent has been an especially sore point with regards to afforestation schemes across the country. As CR Bijoy of the Campaign for Survival and Dignity (CSD) says, “The forest is a highly contested terrain, for its resource potential by businesses for profits, both through extraction and conservation – mining, water, timber, forest produce, knowledge on biodiversity and bioprospecting, carbon sequestration and carbon credits, tourism, ecosystem services, etc.” Bijoy, whose organisation has worked on natural resource politics and governance issues for many decades, adds, “Not only is the diversion of degraded forest land for compensatory afforestation illegal on account of FRA and Forest Conservation Act, 1980, violations, but also for not providing compensation and rehabilitation under the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013, which specifically requires recognition of forest rights, consent and compensation for the loss of forest rights as defined under FRA.”

Even if these jarring conflicts with people’s rights are overlooked, government afforestation activities, which have accrued funds amounting to over $8 billion, are also in fact adding to India’s climate burden, instead of reducing it. As Anand Osuri, a scientist with the Nature Conservation Foundation (NCF), Mysore, had written in this report, “Monoculture or species-poor plantations cannot replace the climate-regulating functions provided by natural forests. This is especially true in the face of disturbances such as droughts, which are predicted to increase in frequency and intensity across India and many other regions globally. Thus, even as India’s overall forest cover is reported to be increasing, the expansion of plantations at the cost of natural forests could result in less effective climate change mitigation overall.” Osuri was making this observation based on a study published in the Journal of Environmental Letters. The study had looked at the Western Ghats and estimated aboveground carbon storage in natural forests as well as in teak and eucalyptus plantations. Most afforestation work sees the planting of commercial species such as teak, eucalyptus, acacia and bamboo.

As Professor Jagdish Krishnaswamy of the Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (ATREE) says, “If you talk about some of our big national carbon stocks, they are in places like the Western Ghats, the Himalayas, and the central Indian highlands. These are our precious ecological assets. Diversion of such areas for development projects and other types of land use should be minimised and other non-climatic stressors need to be managed. Afforestation as it is practised now is not the solution. Since they can never replace original forests.”

Inclusive climate action

Instead of engineering a situation where millions of forest-dependant peoples’ rights are constantly at loggerheads with decisive climate action, the solution seems to lie in co-operation and inclusive climate action. Localised solutions, which are people-centred not only receive better reception, but are also more effective in mitigating or adapting to climate change, as the situation demands. In the region of Ladakh, local researchers and scientists have devised ice stupas to store water from glacial melt to deal with water shortage in the summer months. In India’s north-east, the state government of Meghalaya has begun supporting community-led conservation programmes to negotiate climate-change-induced risks in the region.

The FRA itself has one of the strongest conservation provisions in Indian law. As Ravi Chellam, wildlife expert and the CEO of Metastring Foundation, Bengaluru, states in this report, the FRA provision of establishing a ‘Critical Wildlife Habitat (CWH)’ aids conservation of wildlife and forests enormously since a forest classified as a CWH cannot be subsequently diverted for any other use by any entity. He argues that even the Wildlife Protection Act (WLPA) does not have such a stringent measure for conservation, since a protected area can be denotified according to the provisions of this law. Also, as Chellam rightly points out, in India, wildlife is not restricted to protected areas alone. Therefore, community participation is essential if effective conservation is to take place.

On the few occasions where FRA rights have been awarded to communities, the region’s forests have seen an increase. In Maharashtra, post distribution of Community Forest Rights (CFR), forest cover has increased by 3%. This is also the case in Odisha, the most proactive state with regards to the FRA in India. In Odisha’s Similipal Biosphere, awarding forest rights for tribal communities living in and around the biosphere has enriched the region’s biodiversity, improved people’s livelihood as well as recognised the traditional way of life of forest-dwelling people of the region. The law has also significantly reduced left-wing extremism in the region. Since their Community Forest Rights (CFR) was recognised in 2015, the Similipal story has shown that FRA, when applied diligently, can result in a real ‘win-win’ situation for all stakeholders of India’s forests.

This has also been the case in other countries across the world where similar community conservation efforts have been encouraged. These include examples in Mexico, multiple African countries and closer home, in Nepal where community-based forest management of more than 18,000 community forests has helped reduce poverty and deforestation. Forest resources, such as non-timber forest produce (NTFP), are the primary source of income for many tribal communities across India. It is estimated that over ₹2 trillion worth of NTFP is collected by forest-dwelling communities across India and over 90% of them depend on NTFP for their livelihood. Preventing these millions of people access to their livelihood options will also mean the need for creation of additional employment. With India’s current working-age population estimated to be over 800 million, this additional job-creation burden will only further stress the system and inadvertently impact its climate-change adaptation and mitigation potential.

The need of the hour is to build trust and listen to all stakeholders involved for inclusive, people-friendly solutions. As Shomona Khanna, a lawyer practising in the Supreme Court and former advisor to the Ministry of Tribal Affairs (MoTA) says, “There is a need to re-orient this approach at a fundamental level, by acknowledging the vital importance of indigenous knowledge and practices for protecting forests and biodiversity, by involving them in a real and meaningful way. By this I mean that it’s not just a matter of getting a ‘no-objection certificate’, or a yes/no answer, but there is a need to involve Adivasi and forest-dwelling communities in decision-making by giving them the space to contribute their knowledge, experience, and indeed their aspirations, to the process of governance itself.”

Khanna feels that this would provide a unique solution in which Adivasi communities are allowed to take the lead. As she adds, “If we trust forest-dwelling communities to take decisions wisely and fulfil the responsibility vested in them by a variety of laws and by the Constitution itself, that is, to protect and manage the forest resources under their stewardship in a manner that is beneficial to the environment, to their own livelihood, and also to future generations, there will be a groundswell of creative collaboration. Certainly, this change of perspective is difficult for the forest bureaucracy after more than 150 years of mistrust ingrained through exploitative colonial forest laws, but a genuine effort in this direction must be made.”

This is the third and final part in Carbon Copy’s series on the realities of India’s afforestation and forest conservation policies.

About The Author

You may also like

Empowered local forest governance supports forest restoration: Study

Human rights, environmental issues dog Adani’s bid for inclusion in Dow Jones Sustainability Index

America’s shale story has a new chapter in the offing

The perils of taking forests for granted

The unflattering reality of India’s lofty plans for its forests