The final methodology for green credits for tree plantation activities seems to legitimise greenwashing, raising questions about the programme’s tangible environmental benefits

India’s Green Credit Programme (GCP), currently under construction, saw its first discernible wall erected in February. The country’s environment ministry notified the final methodology for the issuance of green credits for the plantation of trees. The notification is the first significant development after Prime Minister Narendra Modi drew the spotlight on ‘Green Credits’ at the opening of the COP28 in Dubai as “a campaign that moves beyond the commercial mindset of carbon credit and creates a carbon sink with public participation.” This pitch was followed by the launch of an Global Green Credits Initiative along with UAE’s COP Presidency.

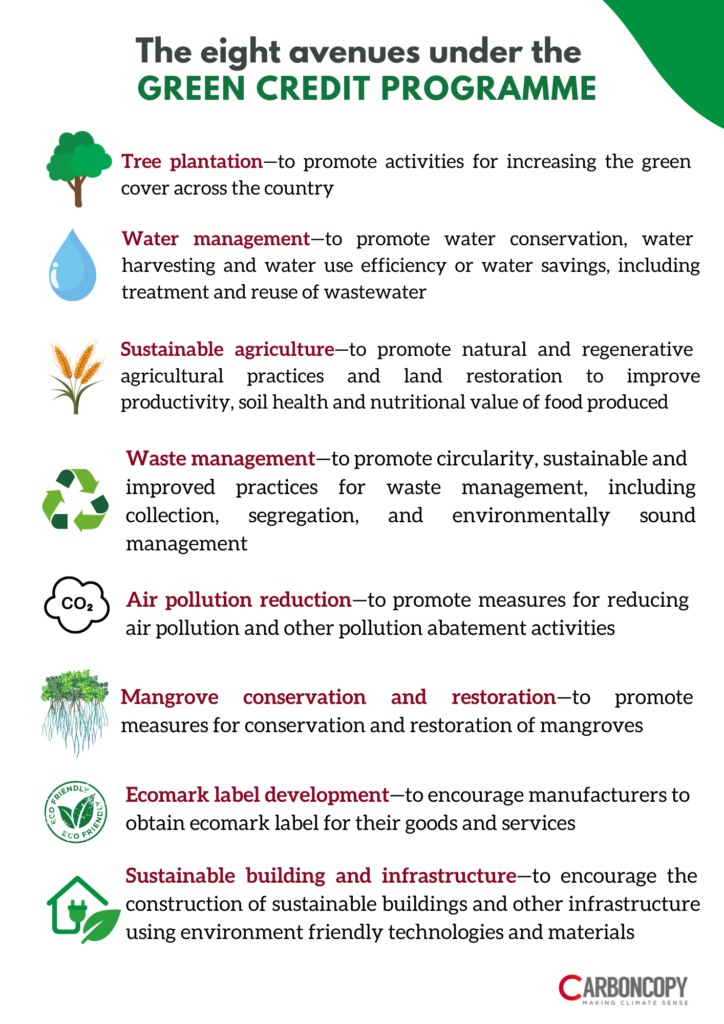

The rules for the governance of India’s GCP was notified in October 2023, weeks before Modi’s appearance at the COP in Dubai. Up front, the scheme is framed as “an innovative market-based mechanism to incentivise environment positive actions” among commercial entities and individuals. Envisioned as a voluntary market mechanism that runs in parallel to the Carbon Credit Trading Scheme (CCTS) (which will be based on compliance of emission reduction mandates for chosen industries), the GCP aims to generate tradable units that reflect positive environmental impacts of interventions and activities through any of eight identified avenues.

India has a $10.1 trillion funding gap to meet its net-zero by 2070 commitment. The Indian Carbon Market, which includes both green credits and carbon credits, expects to channel funds through the two market schemes to fund its net-zero goals. The GCP and the Carbon Credit Trading Scheme (CCTS) have another foundational difference that stems from how tradable units are defined. While the credibility of carbon credits relies on the coherence of the credit with a physical and quantifiable unit i.e. the amount of carbon emissions, green credits are governed by broader, more conceptual boundary conditions without a clear physical standard, and articulated simply as units that are provided for activities delivering a “positive impact on the environment.” What exactly this means is revealed only by the individual methodologies that are developed for each of the eight identified avenues for environmental sustainability interventions and activities—how credits will be generated and the basis on which they will be verified.

A green-tinted resource grab?

The first of these methodologies was finalised in late February 2024 for tree plantation activities, a little more than four months after the draft methodology was published for public feedback and comments.

Under the February notification, the central and state forest departments have been tasked with identifying and making available ‘degraded land parcels,’ at least 5 hectares in area, under their administrative jurisdiction and management, including open forest and scrub land, wasteland and catchment areas for tree plantation activities aimed at increasing India’s green cover. The Green Credits website so far lists 161 “approved” parcels of land across 9 states and the Union Territory of Daman and Diu accounting for 3,664 hectares.

The Indian Council of Forestry Research and Education (ICFRE), which has been denoted as the administrator for the Green Credit programme, will be in charge of receiving applications and proposals from entities willing to undertake tree plantation activity and allocating land from the parcels identified. Upon the payment of tree plantation and administrative costs, the forest department will carry out the tree plantation under direction from the ICFRE and in accordance with the work plan for the project. The timeline to undertake this activity has been set as two years from the date of payment. The methodology specifies that each tree planted under the scheme would generate one credit, subject to a minimum density of 1,100 trees per hectare. Issued credits can then be traded between entities and used to meet Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) obligations of companies—from which demand for credits are expected to be generated.

Interestingly, the final rules reflect a massive departure from the draft methodology issued in October 2023. For one, the draft methodology had proposed a range between 100-1,000 trees per hectare along with an identification of species in line with agro-climatic and soil conditions. It also proposed a phased issuance of credits over a 10-year period following plantation in order to incorporate factors such as survival rate, tree growth and crown cover. Additionally, a multiplication factor in accordance with annual rainfall levels found a place in the draft. It is important to note that while survival rates of trees in plantations vary greatly from case to case, literature indicates an average survival rate of around 50% for public tree plantations. The choice of species, method of plantation and post-plantation care have been identified as strong influencing factors in the survival of species.

The final notification, however, does away with all details aimed at efficacy and credibility of the credits, and instead replaces it with one line stating the 1,100 tree limit “based on the local silvi-climatic and soil conditions.” Ostensibly, the hike in the target number to beyond the upper limit suggested in the draft is in lieu of the factors that reflect species suitability, tree survival and growth. Under the final framing, the activity of plantation by itself is eligible for credits, all of which can be granted upon verification. Notably, however, the final methodology remains conspicuously silent on how this verification will be done and who will be responsible for it—an aspect which had been fleshed out in relatively greater detail in the draft. These issues raise important questions around the real-world credibility and fungibility of these Green Credits.

Has the final methodology for green credits issued through tree plantation activities legitimised greenwashing, rather than provide any tangible environmental benefit?

This kind of credibility crisis is a symptom of the current Voluntary Carbon Markets regime with the efficacy of many projects and carbon credits coming under question in media and research. This has led to a steep fall in liquidity and confidence in the VCM, with many buyers reducing their activity. According to S&P the Platts Nature-Based Avoidance price, which reflects the most competitive internationally fungible carbon credits issued by nature-based projects such as REDD+ projects, continues to languish at record lows. The Platts-assessed nature avoidance prices plummeted to just over US$3/ tonne of CO2 at the end of January 2024, 81% lower than the high prices of over US$11.50/tonne of CO2 seen a year ago in January 2023.

Interestingly, the tree plantations will also be eligible for the generation of carbon credits, which can be traded through the parallel CCTS, but through a separate process of assessment, monitoring and evaluation that would be overseen by the CCTS governing structure.

The compensatory mis-direction

An additional layer of complexity comes from the explicit provision for the usage of Green Credits for compliance with the compensatory afforestation rules under the Forest (Conservation) Act/ Van (Sanrakshan Evam Samvardhan) Adhiniyam, 1980, which mandates project developers to replace trees cut down on forest lands through plantations raised on alternate sites. A significant change in these in the rules for compensatory afforestation in 2022 allowed companies required to carry out compensatory afforestation to simply buy up existing privately owned plantations rather than setting up fresh plantations, implicitly diluting the effectiveness of the motive to replace lost forest cover. Eligible plantations, however, had to be at least five years old, spread across at least 10 hectares and have a canopy density of at least 40% The GCP now goes one step further by eliminating these conditions and opening up the possibility of meeting compensatory afforestation requirements through the purchase of green credits.

A letter signed by 91 former civil servants in the weeks after the methodology was notified raised strong objections to the rationale of this provision. “No amount of money can be a substitute for the land required for our forests, and for our biodiversity and wildlife to thrive. Yet, the government is trying to make it easy for entrepreneurs and industrialists to acquire forest land by permitting them to offer, in exchange, money (in the form of green credits), instead of land for land as was the case so far. When forest land can be so easily obtained by private entrepreneurs, it does not take much imagination to realise that the extent of land legally classified as forests at present will steadily shrink until there is virtually nothing left. A new set of Green Credit invaders may ask for diversion of some of our densest and best protected forests for commercial purposes like mining, industry and infrastructure,” the letter reads.

Researchers suggest that market-based mechanisms in India need to give importance to biodiversity values and ecosystem service provisioning to benefit local communities democratically. They say the Indian landscape has reported that efforts to conserve, increase or protect forests may be misdirected, for example in choosing the wrong tree species for reforestation. The study recommends that projects selling credits must inform investment decisions. If the focus is restricted to only carbon sequestration, there is a higher likelihood of developing near-monocultures of fast-growing tree species. Not only the carbon market quality would be negatively affected by such activity, but it will also lead to an ensuing disturbance of the entire landscape, both from ecological and socio-economic perspectives, the study concludes.

A blind numbers chase

While tree plantations remain the only activity for which a GCP methodology has been finalised, a draft methodology for the issuance of Water Harvesting based Green Credits was also published in October 2023. Water harvesting activities covered under the scheme, as per the draft, have been reduced to conservation structures such as earthen ponds and poly tanks—with 100 cu.m of capacity eligible to generate 75 credits. Meanwhile, other interventions that increase water-use efficiency, groundwater recharge and other in-situ conservation techniques have been left out of the draft.

Similar to the draft on Tree Plantations, credits for water conservation projects have been proposed in a phased manner over 10 years following the completion of construction. Unlike the Tree Plantations draft though, 60% of the credits have been proposed to be issued in the first year immediately following construction. Multiplication factors in accordance with the annual average rainfall levels have also been included in the draft to encourage the undertaking of projects in rain-deficit regions. If the final methodology for tree plantations is anything to go by, one would expect much of this qualitative nuance to be left out of the final version in favour of heightened focus on quantitative targets—a rationale that echoes the target of digging 2 million farm ponds that the NDA government had issued in its first term and the success of which was dubious in terms of utility and longevity of the harvesting structures that were constructed.

The Indian government’s apparent fixation with high number targets must be seen in the context of the country’s commitments on climate and environment. India’s Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) toward the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the Paris Agreement includes the creation of an additional carbon sink of 2.5 to 3 billion tonnes of CO2 equivalent through forest and tree cover by 2030. Incidentally, this remains the NDC target that has seen the least progress so far. India is also a signatory to the UN Convention on Biodiversity (UNCBD) Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) of 2022, which entails targets to conserve 30% of degraded ecosystems and 30% of of terrestrial and inland water areas, and of marine and coastal areas, by 2030. Under the UN Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD), the Indian government updated its 2030 target to restore degraded lands to 26 million hectares in 2019.

When seen in this context, the significance of the GCP as a centrepiece of India’s contemporary environmental policy becomes clearer. What also becomes clearer is an overarching strategy of relying on indirect quantitative indicators such as number of trees or water conservation structures rather than more direct qualitative indicators of the impact delivered by interventions in order to meet these commitments. This strategy may be easier to frame narratives around. They, however, also carry a significant risk of dissonance between intention and outcome of investments—a central tenet in maintaining the integrity of markets.

Another aspect that comes to the fore is the progressive shifting of environmental and climate responsibilities away from public institutions such as forest departments and toward private investors. While this is in line with a broader international recognition that sources of finance for climate and environmental action must include private sources, complete abandonment of qualitative standards to accelerate this shift has perilous potential that includes not only economic implications of poor credibility, but also risks of larger ecological deterioration. In framing the GCP rules and methodologies, the Indian government faces a choice between creative accounting and credibility. Failure to prioritise the latter—thereby opening the door for greenwashing—as is evident in the final methodology for Green Credits issuance through tree plantations, will amount to little more than a discounted transfer of natural wealth into private hands in a way that almost entirely cuts out the public and its interests from the deal.

About The Author

You may also like

BRICS bloc proposes more multilateralism, sustainable development of Global South

Climate Talks in 2025: Converging Crises, Rising Stakes, and Diminished Returns

Countries agree 10% increase for UN climate budget

Targeted co-financing can solve the challenge of just transition in emerging economies: Report

Can biochar be India’s missing link to carbon capture?