Overlapping concessions and weak safeguards risk deepening biodiversity loss during the energy shift

Alongside the climate crisis, the world is also facing another crisis: the rapid loss of biodiversity. In their latest assessment, the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) found that the average abundance of native species in most major terrestrial biomes has fallen by 20% since 1900. One of the main reasons may be that global indicators of natural ecosystem extent and conditions have shown an average decrease of about 47% of their estimated natural baselines, threatening approximately 25% of all animal and plant species studied to the brink of extinction.

The extinction or the reduction in population of plants or animals will undoubtedly have an impact on human existence. For example, the declining population of Sumatran tigers has led to a reduction in the number of wild boar predators. As a result, the wild boar population has become uncontrollable and they are increasingly at risk of entering agricultural areas and houses around the forest.

To mitigate the crisis, the whole world — including Indonesia — agreed on a target of increasing protected areas to 30% of the land and sea area in their respective countries by 2030. However, as of 2021, Indonesia’s terrestrial protected areas only cover 12.2% of its total area, while its marine protected areas only cover around 3.1%. With time running out to meet its targets, Indonesia’s efforts to protect biodiversity also has a major stumbling block: the extraction of fossil resources such as coal — many of which are located in forested areas.

Subsequently, a recent study by AEER (Ecological Action and People’s Emancipation) in East Kalimantan highlights how 435,000 hectares/ha (29%) of the total coal concession area in the province overlaps with forest areas. Of that figure, around 19.8% are key biodiversity areas (KBA) that hold so much endemic biodiversity that make them essential to the natural integrity of East Kalimantan. This AEER study is a fine addition to our long list of reasons to accelerate the energy transition. By utilising more renewable energy and phasing out fossil fuels, Indonesia can at least mitigate the climate crisis and biodiversity crisis that are jeopardising life on earth.

Biodiversity Areas Under Threat

There are at least six KBAs in East Kalimantan; namely the Central Mahakam Wetlands, Long Bangun, Sangkulirang, Mahakam Delta, Gunung Beratus, and The Samarinda-Balikpapan Forest. All of them serve an important function for species survival. The Mahakam Delta KBA is home to the proboscis monkey (Nasalis larvatus), a threatened endemic primate. The Kutai KBA is also home to Bornean orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus) and ironwood trees (Eusideroxylon zwageri) that are rarely found elsewhere. Unfortunately, five of the six KBAs remain outside the conservation area, so they are not legally protected. In fact, according to the AEER study, around 54.6 thousand ha of them are actually included in coal concessions.

This overlap greatly endangers the sustainability of KBAs due to the expansion of coal mining. Compared to 2009, in 2023 the province’s coal production has increased by 132%. Increased production directly translates into increased clearance of forested areas, including KBAs, that overlap with coal concessions. In addition to uprooting centuries-old trees, the clearing also reduces the living space for various species.

In the case of orangutans, for example, by 2025 alone there will be around 37 individuals that have ‘left’ their habitat and entered production areas such as mining and plantations in East Kalimantan. They have lost their home range and food sources, so they have no other recourse but to seek for food and shelter in places that have been degraded by humans. It is important to remember that the influx of wildlife as forests shrink increases the risk of new diseases spreading to human settlements. For example, the Ebola and Marburg virus infections that broke out in Uganda spread as apes increasingly descended on human settlements.

AEER noted that most of the concessions in East Kalimantan (178 out of a total of 310 concessions with a total area of around 530 thousand ha) will expire in 2030. However, reflecting on the case of granting mining concessions for the former PT Kaltim Prima Coal to Nahdlatul Ulama, there is always a risk that the government will extend dredging activities. Especially since East Kalimantan has an estimated 11.59 billion tonnes of coal reserves.

Coal Hazards: A National Overview

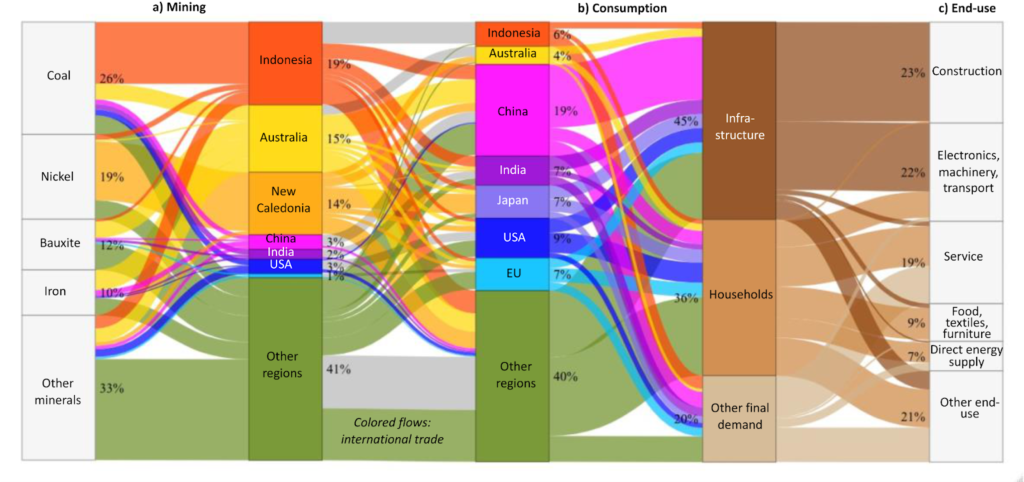

East Kalimantan seems to be a harrowing hotspot for coal mining’s impact on biodiversity. According to a 2022 study by Cabernard and Pfister, 14% of the global mining impacts on biodiversity occurs in Indonesia where an estimated 50% comes from the impacts of coal mining operations.

The magnitude of this impact is due to the nature of Indonesia’s coal resources – which are mainly located deep in its forests. As a result, most coal mines in Indonesia require the clearing of forests which translates into severe disruptions of the local ecosystem. This is a stark contrast to some coal-rich areas in Australia, which are located in savannahs or sparsely vegetated plains.

In addition, because coal is mostly used to generate electricity, the impact of coal-fired power plants on biodiversity is even greater. The massive clearing of forests for coal means that the footprint of biodiversity loss due to coal plants is not to be taken lightly, as it is 10 times greater than renewable energy such as solar and wind.

The magnitude of this impact, as explained by the Cabernard and Pfister study , extends to the footprint of biodiversity loss due to coal-fired power plants. The share is about 95% compared to other uses (such as cement and steel production). Apart from biodiversity, coal mining has also long been the culprit of many problems such as extreme poverty due to a polluted environment, methane and CO emissions, land conflicts, as well as social issues in coal-producing areas.

A Comprehensive Energy Transition

Biodiversity is not just “another aspect” of life on earth, biodiversity is integral to human life. The destruction of the integrity of natural biodiversity also means a threat to our survival. The government needs to uphold this paradigm by wholeheartedly protecting it.

One step that needs to be taken immediately is to designate KBAs in East Kalimantan and other areas as conservation areas. This creates legal certainty so that the state can utilise its apparatus and issue policies to protect biodiversity.

The designation then needs to be accompanied by a massive re-evaluation of concessions that overlap with forested areas and KBAs. To protect biodiversity, these areas should not be mined — so concessions with areas overlapping with KBAs need to be canceled.

For KBAs that have already been excavated, the government must ensure that concessionaires comply with reclamation and post-mining obligations. Furthermore, it is important to outline that reclamation activities should aim to restore the land and biodiversity to their original condition — not just the replanting of trees.

The government also needs to review the granting of so many concessions that have led to the excessive mining of Indonesia’s coal reserves. In addition to its environmental impacts, excessive mining of its coal reserves also risks disrupting Indonesia’s energy security in the long term.

Therefore, instead of mindlessly granting mining concessions, the government should strategically boost collaborative forest management practices with local communities. Management by communities, especially indigenous communities, has been proven to better ensure the sustainability of forests and safeguard the livelihoods of local communities.

Subsequently, the acceleration of renewable energy development can also reduce Indonesia’s need for coal. Under certain conditions, solar energy development has been shown to increase biodiversity.

Finally, while accelerating its renewable energy deployment, the government also needs to oversee other programmes related to energy transition — such as critical mineral mining and electric cars, which have also been proven to have a negative impact on communities in eastern Indonesia. The hope of the people is that the end of the fossil energy era does not create new mining problems in the future.

This article was initially published in Transisi Energi Berkeadilan