Its models fail to reflect and preserve the principles of equity and rights to development while charting decarbonisation pathways

The pre-eminent authority on the science of climate change, the Inter-governmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), on Monday published the final report from its sixth assessment cycle (AR6). The Synthesis Report (AR6 SYR), which is essentially a compilation of the most requested hits from the three working group reports published in 2021 and 2022, reiterates warnings of a closing window for emission reductions needed to avoid the worst impacts of climate change. While the concluding report of AR6 holds little in terms of fresh information, it comes at a crucial juncture in the charting of long-term climate action. The fact that this will be the last IPCC report for several years, before reports from the seventh assessment cycle (AR7) start rolling out, only adds to the significance of the contents of the report.

Key among these contents are the models described in the IPCC’s AR6 and the newly published Synthesis Report. Despite their appreciable importance to key climate policy questions of the day (or because of it), questions are being raised around the real-world feasibility and differential implications held by the models for developing and developed countries. How realistic are the futures described in IPCC’s models? To what extent do they reflect and preserve the principles of equity and rights to development while charting decarbonisation pathways?

The many inequities of modelling

Emissions from three fossil fuels—coal, oil and gas—have caused the climate havoc we see today. Since carbon is carbon irrespective of its source, one would imagine mitigation scenarios outlined by the IPCC to be agnostic to the source. The models, however, single out only coal, predominantly used in the developing world, for rapid and drastic declines.

Questioning socio-political feasibility of the IPCC’s focus on coal phase-outs, a new study published in Nature on February 6, 2023, points to an underestimation of levels of reduction in oil and gas to limit warming within 1.5˚C. It finds that IPCC pathways require coal generation to decline in countries like China, India and South Africa “twice as fast as achieved historically for any power technology in any country.” And that if more realistic pathways are drawn up, it would require the Global North to cut emissions 50% faster.

And while there is an argument that the climate crisis is unprecedented and so, efforts have to be more radical than in the past, the real weight of the burden and who ends up bearing it is the question. “Reducing oil dependence following the 1970s price spikes, or phasing out nuclear after the Fukushima disaster required huge policy efforts,” explained Greg Muttitt, lead author of the paper and a researcher at the International Institute for Sustainable Development. There were also other factors at play in such energy transitions like the collapse of the Soviet Union and effects of wars and sanctions.

Such IPCC-guided mitigation efforts are disproportionately shared between countries, only some of whom would be required to make historically unprecedented efforts. The median IPCC 1.5°C pathway reduces coal power globally by 87% by 2030 and by 96% by 2035. For South Africa, which is dependent on coal for around 80% of its power, this pathway entails replacement of an overwhelming portion of its power fleet within a decade. On the other hand, global gas power generation, most of which occurs in high-income countries, falls by just 14% by 2030 in the median pathway. And oil by just 10% by 2030. “An excessive focus on coal phaseout as the primary mitigation tool can create a perverse narrative that developing countries must contribute more to mitigation,” the paper states.

A major implication of the paper is that if IPCC pathways do not describe a realistic future, they become less useful as policy guides. For example, to point to required levels of emission cuts in the Global North. Consider how the US emits more CO2 from oil than India does from coal, but there is virtually no discourse calling for a scale down of such production that can correspond to the global recognition to do the same for coal. India’s per capita coal consumption is also only a little more than half the world average, lower than in countries like the US and Germany.

In their case against the oil giant Shell, the Dutch environmental organisation Milieudefensie, too, notes that IPCC pathways calling for faster phaseouts for coal than oil and gas stem from “theoretical assumptions” that are “somewhat at odds with the principle of Common But Differentiated Responsibilities”. Globally too, the oil and gas sector is responsible for 25% more CO2 emissions than coal.

In their “more societally feasible” scenarios, the authors note that countries in the Global South would still have to reduce coal power generation by a third by 2030, and give it up fully by 2050. But they call for more drastic reductions in oil and gas in the Global North to make up the difference. More broadly, they outline higher Global North emission reductions across all sources of emissions: oil, gas, coal, cement and land use change. But the biggest changes i.e. departures from scenarios outlined by the IPCC, occur in the transport and industry sectors, and in emissions from oil and gas.

Modelling efforts can be inherently inequitable

IPCC pathways are generated using global integrated assessment models (IAMs), which combine information from various scientific disciplines, taking into account both human and earth systems and interactions between the two. In essence, IAMs are complex models that examine possible futures of energy and climate systems and also the economy. The aim is to provide policy relevant insights.

However, IAMs also have limitations given how they represent the world from purely technical and economic perspectives. Coal delivers the least energy per tonne of CO2 emitted, and clean alternatives are available. Costs of labour and land are cheaper in the developing world so running these new technologies would be cheaper than in the developed world. No wonder then that IAMs, which prioritise least-cost pathways, rely very heavily on a coal phase out to achieve emission reductions. But this ignores socio-political equations like the burden of energy transition on poorer countries and also economic costs like interest rates. For instance, consider how clean energy financing in developing countries can be up to seven times higher than in the US or Europe. But IAMs assume that all capital required is available.

Aayushi Awasthy, PhD Economics (energy), University of East Anglia, explains that when looking at an analysis from an implementation perspective, a model can, for example, say that costs of setting up a wind farm in India are low. But, she adds, this does not account for India-specific problems on how the farm would be set up, apart from overnight capital expenditure. So we need coordination between global, national and state-level modelling to be able to adequately address ground realities.

IAMs also have blindspots when it comes to their assessments of gas. Methane has a higher warming potential than CO2 but a shorter lifespan. So the use of 20-year vs 100-year equivalencies determines how much gas you should or shouldn’t use. “The short run implications of gas are far worse than normally modelled,” says Rahul Tongia, senior fellow at Centre for Social and Economic Progress. There are also other issues like the underestimation of methane leaks.

The other issue that is rarely noted are grid-specific implications of high renewable energy and corresponding needs for storage. Each country is different and India is coal-heavy. “This makes renewables-based flexibility harder [than in countries which have gas as a backstop] because India would need more storage to allow more renewables than most countries or even the global average,” Tongia notes. But it remains unclear if IAMs are coupled with country-specific grid modelling.

IAMs also do not consider past emissions. Modellers find it “challenging to envision truly equitable emissions pathways because that would mean high-income countries would have to reach net-zero immediately,” explains Aljoša Slameršak, PhD researcher at Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. High-income countries like those in Europe and the US have used more than their fair share of the global carbon budget and are still emitting high levels of CO2— both in absolute terms and on a per capita basis. But because such high mitigation burdens on these countries are considered infeasible, “IAMs resort to the “practical” solution where emissions burdens are distributed cost-effectively,” she adds.

But such cost-effective pathways entail stark trade-offs between equity and economics. Tongia points out that “even small shifts in economic efficiency can have 10x shifts in equity.”

It is this same emphasis on cost-effectiveness that allows for a problematic reliance on tree-planting efforts. “Because it’s impossible to scale up existing technologies at deployment rates that could be considered reasonable, vegetation models are coupled with IAMs,” explains Tejal Kanitkar, associate professor at National Institute of Advanced Studies in Bangalore. And because afforestation efforts, especially those carried out in developing countries, are assumed to be cheap, IPCC scenarios emphasise the role of land-based CO2 sequestration and even technologies such as bioenergy and carbon capture in the Global South.

“IPCC pathways often get used uncritically as policy guides, which can give a distorted picture of what is needed to achieve climate goals. A modeller based in Europe will tend to have the barriers to electrifying the car fleet more present in their mind because they hear and talk about them every day than the barriers to replacing power infrastructure in the Global South.”

– Greg Muttitt, International Institute for Sustainable Development

And while modellers may well be aware of all such limitations, “IPCC pathways often get used uncritically as policy guides, which can give a distorted picture of what is needed to achieve climate goals,” Muttitt said. Also, even though IAMs are largely considered to be objective, modellers and researchers are still human with their own biases. “A modeller based in Europe will tend to have the barriers to electrifying the car fleet more present in their mind because they hear and talk about them every day than the barriers to replacing power infrastructure in the Global South,” Muttitt notes. Hence, we end up with models that better reflect real-world difficulties where the IAM modellers are based, which is mostly in the Global North.

Then there’s the fact that IAMs do not take into account failures of the developed world in mobilising climate finance for energy transition in the developing world. So one could argue that IAMs, which play a big role in shaping climate debate, provide quantified guidance on mitigation action alone but not on climate finance.

“IAM models don’t claim to be fair,” Awasthy points out. They only claim to present the cheapest option, assuming that a single global government is in-charge of mitigation action. The analogy in economics is a ‘socially benevolent dictator’ assumption. “It’s when economists don’t want to think about politics, geopolitics and other considerations. It has merit in its own right but can’t dictate the actions of developing countries,” she adds.

These limitations have not escaped the attention of IPCC authors. Following lengthy discussions at the plenary meeting for the Synthesis Report, a disclaimer was elevated from the footnotes to a box on modelling scenarios included in the report — “Modelled scenarios and pathways are used to explore future emissions, climate change, related impacts and risks, and possible mitigation and adaptation strategies and are based on a range of assumptions, including socio-economic variables and mitigation options. These are quantitative projections and are neither predictions nor forecasts. Global modelled emission pathways, including those based on cost effective approaches, contain regionally differentiated assumptions and outcomes, and have to be assessed with the careful recognition of these assumptions. Most do not make explicit assumptions about global equity, environmental justice or intra-regional income distribution. IPCC is neutral with regard to the assumptions underlying the scenarios in the literature assessed in this report, which do not cover all possible futures.”

IPCC projects inequities far into the future

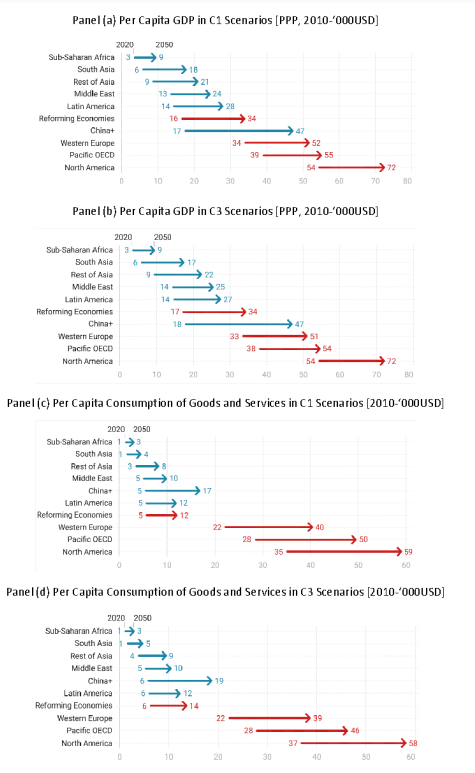

On November 3, 2022, research that shows how IPCC pathways project global inequities far into the future was published in pre-print form. Conducted by scientists at NIAS in Bangalore and MS Swaminathan Research Foundation in Chennai, the study found stark differences in both per capita GDP and per capita energy consumption that maintain existing inequities between the developed and developing world even up to 2050.

Except for China, “the per capita GDP, in the rest of the developing world in 2050 is restricted to USD 9,000 – USD 28,000 at the most and for South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa at even lower levels of ~USD 18,000 and ~USD 9,000 respectively,” the paper states. It adds that this is “lower than the current per capita GDP levels of developed countries as a whole and much lower if compared to the current per capita GDP of OECD countries.”

The projections for near-term emissions reductions are “even more egregious” from the standpoint of equity and Common But Differentiated Responsibilities and Respective Capabilities,” Kanitkar points out. Developing countries are projected to start reducing emissions, from their already low levels of per capita emissions, immediately and deeply. In fact, in some scenarios , Sub-Saharan Africa reduces emissions at rates faster in the near term as compared to developed countries. “There are serious questions about not only the equity, but also the feasibility of these scenarios, that become relevant given such projections,” she adds.

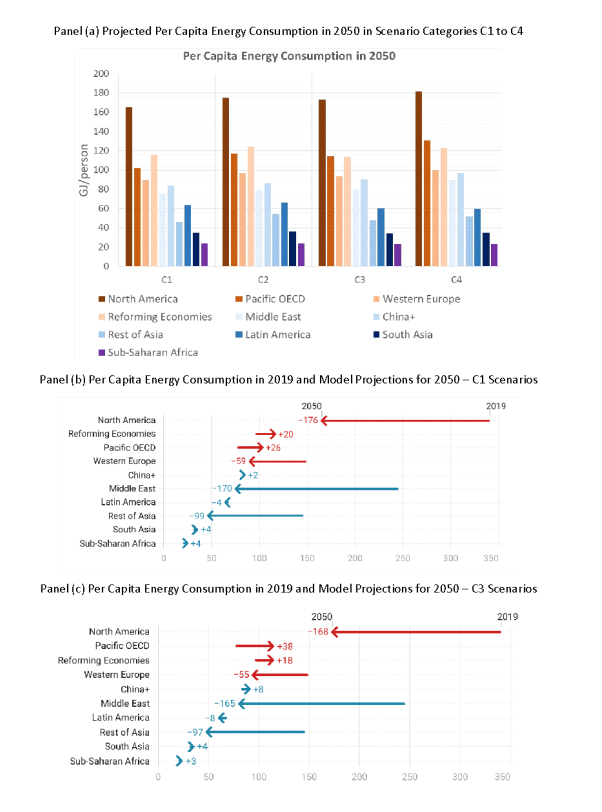

The study originally was based on the 367 scenarios of one model intercomparison project. The final, however, is based on 556 out of 700 scenarios in the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report on mitigation. All of them project an unequal future that perpetuates current developmental inequities. A crucial point here is that it’s not just fossil fuel use but even overall energy consumption, including from renewables and consumption of goods and services too are restricted for developing countries.

“It’s an excellent paper and the finding is interesting because it proves that peoples’ aspiration is not built into any of the scenarios in the models,” Awasthy says. She added that more work needs to be done on the theme, “led by developing countries so they can shape the analysis. A balanced analysis has to be both realistic and aspirational.”

Across all scenarios, North America is projected to have the highest per capita energy consumption in 2050, which is about 6-8 times more than Sub-Saharan Africa and around 5 times more than South Asia. A question that arises here, Kanitkar said, is how countries in South Asia and Africa are supposed to achieve development at most with 35 gigajoules of energy per person. And if this is simply a result of end-use of energy, why don’t countries in North America have access to the same energy efficient technology given how they are still using more than around 120 gigajoules of energy per person in 2050.

Such inequitable projections stem from the fact that IAMs freeze income disparities at current levels because they do not consider distributive justice. What this means is that while individual incomes can increase, the differences between them cannot. So regions in the developing world will always be poorer relative to developed world counterparts.

The scenarios also place the burden of carbon removal—both via land-based carbon sinks and technologies like carbon capture and storage—on developing countries because over 65% of CO2 sequestration happens in such countries, the paper shows. This is one reason why the scenarios envision Latin America as reaching net-zero far sooner than many developed countries.

A paper released last year, too, pointed to trends in emission reduction pathways outlined by the IPCC that “perpetuate colonial inequalities. Slameršak is a co-author in this paper.

A just transition away from fossil fuels would require energy convergence wherein reduced energy use in the wealthy countries could make space for higher energy consumption for developmental purposes elsewhere. But instead, the authors say, “existing scenarios maintain the Global North’s energy privilege at a per capita level 2-3 times higher than in the Global South.” IAMs have a blindspot here too given how they factor in only supply-side decarbonisation and do not account for demand reduction.

This paper, too, noted the reliance on “risky” negative emissions technologies like bioenergy with carbon capture and storage in IPCC pathways that result in an appropriation of land in the Global South “to support the Global North’s energy privilege” with other devastating consequences like on food systems, water and biodiversity.

“It’s not that the models that are used to construct these scenarios do not make explicit assumptions about global equity, but that they in fact assume the perpetuation of existing inequities for decades to come,” Kanitkar says.

The dubious reflection of equity and ground realities in IPCC-curated models are likely to come up during the course of inter-governmental negotiations on the direction of climate action. While one can expect intense politicking as countries bargain for outcomes most favourable to them, the challenge confronting the IPCC is larger. The credibility of the panel rests on its ability to minimise ambiguities and provide policy guidance. The removal and remedy of inequities of accepted climate science will likely be key to maintaining this role, and failure to do so effectively could rapidly devolve into an existential threat for the body. As the IPCC closes the chapter on AR6 and begins charting a workplan for AR7, the scientific body will be acutely aware of the distance it must close to maintain its policy relevance. “There definitely is awareness now that things must change. What direction that will take for AR7 is yet to be seen, but the issue of problems with the models has been increasingly raised by India and many others. It is also no longer something that IAM modellers can dismiss,” remarks Kanitkar.

About The Author

You may also like

India’s EV revolution: Are e-rickshaws leading the charge or stalling it?

Loss and Damage Fund board meets to decide on key issues, Philippines chosen the host

Is pine the real ‘villain’ in the Uttarakhand forest fire saga?

NCQG’s new challenge: Show us the money

India’s energy sector: Ten years of progress, but in fits and starts