India’s pesticide-heavy strategy to combat locust attacks is hindered by a massive blind spot when it comes to the long-term impacts on land and water

Large-scale usage of chemical pesticides had been sanctioned to deal with locust attacks of 2020-21, Narendra Singh Tomar, Union Minister of Agriculture and Farmers’ Welfare, told Lok Sabha on September 15.

“Plant protection chemicals” were purchased, Tomar told the Lok Sabha, adding, “spray equipment-mounted vehicles were utilised for ground control and tractors were hired with spray equipment.” Additionally, drones were used for locust control for the first time in the world and one helicopter was also used for aerial spraying.

But scientists have questioned the rationale of such large-scale, indiscriminate chemical spraying.

“Is the fear in India irrational? How many swarms [entered India] over how many days and what was the size of the swarms? Does it impact food security? These are the questions we must ask and this is all basic ecological monitoring,” said Abi T Vanak, a senior fellow at the Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and Environment, a non-governmental organisation that works on conservation and sustainability.

As of August 23, 2020, locust control operations, including the usage of chemical pesticides, were carried out over 287,374 hectares across Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Punjab, Gujarat, Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra, Chhattisgarh, Haryana, Uttarakhand and Bihar.

But “by the time the first 2-3 locust waves came [into India], crops like wheat were already harvested and there were very few standing crops,” said Chandrashekara K, former professor at University of Agricultural Sciences, Bengaluru.

The move to mobilise large-scale chemical spraying equipment, therefore, raises questions about whether cost-benefit analyses were conducted.

Did the Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers’ Welfare assess the extent of potential crop damage from the locust attacks? Did the action taken finally end up costing less than the crop damage that would have occurred otherwise? Does the ministry consider the impact of pesticides on crops as part of the cost of chemical usage? CarbonCopy sent these questions to the agriculture ministry between September 18 and 23, but had not received a response at the time of publishing this report.

Locust swarms of 2020

Desert locusts are short-horned grasshopper species that migrate extensively in swarms and feed on large quantities of vegetation in their migratory path.

This year, from April to August, India saw swarms of locusts, according to Tomar’s response in Lok Sabha, which damaged crops in 10 states: Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Punjab, Gujarat, Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra, Chhattisgarh, Bihar, Haryana and Uttarakhand.

“The actual amount of crop damage [due to locusts] would only be known when crops are harvested from now onwards,” said Sumit Dookia, a Rajasthan-based wildlife biologist and scientific adviser to the Ecology, Rural Development and Sustainability (ERDS) Foundation, a Rajasthan-based conservation organisation. But the damage this year is likely lesser than last year despite the area affected by locusts being larger, Dookia added. The locust attacks during 2019-20 affected 179,584 hectares across Rajasthan.

“Using chemicals is a quick solution and farmers also favour this because of fears of crop damage,” said Om Prakash, programme lead trainer of an agriculture programme launched by Urmul Trust, a Bikaner-based non-profit focusing on social and economic issues in Rajasthan. Prakash comes from a family of farmers.

But was such large-scale action, which included seemingly expensive items like drones, helicopters and tractors with spray equipment, a proportionate response?

Climate connection

In India, the highest risk of invasion by locust swarms, which originate in the Horn of Africa and the Middle East, is during the months of August and September.

But this year, the swarms arrived early because of the climate change-linked unseasonal rainfall in the desert regions of Africa and the Arabian Peninsula caused by unusually warm waters in the Indian Ocean. This led to early breeding of locusts. The locust swarms of this year were greater in number and have raided crops at a greater frequency than before.

“Even as late as September and October, the local locust surveillance and control department was monitoring clusters in Pakistan that could have made the jump to India,” Dookia said. He added that the local locust department has already announced that next year too the attack by locust swarms will be similar in scale.

And so, it is very likely that instances of these kinds of pest attacks will continue to occur – if not get worse – in the future. But the concern in India is whether large-scale usage of chemical pesticides is warranted each time that locust swarms come into the country.

Poor surveillance, monitoring

Although locusts enter border districts of Rajasthan each year, the attack this year was the biggest one since 1993, said Dookia. “In Rajasthan, 20 out of 33 districts were under locust attack,” he added.

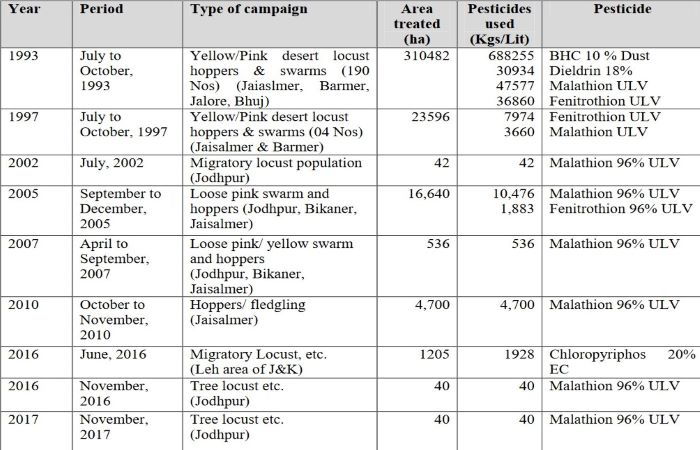

In India, the last full-blown locust attack occurred between 1959 and 1962, when the crop damage was estimated to be around Rs50 lakh. Relatively smaller scale attacks were also reported in 1978 and 1993.

“Since the time of British colonisation till today,” Dookia said, “India has relied on chemical sprays to combat locust-related crop damage. This has been so predominantly because we wake up at the last minute… only after locusts are already here [in Rajasthan].”

“We are very poor in surveillance and monitoring,” said Chandrashekar. “Following rainfall in Africa in September and October, we have to gear up for monitoring because once locusts come into India, there is very little one can do.”

With reliable information, policy action could be measured in terms of assessing whether chemical pesticides are required. If potential crop damage was likely to be heavy without interventions, explained Chandrashekar, decisions could be taken regarding controlling the multiplication of locust populations in terms of where to spray chemicals and at what scale.

In essence, all we needed was primary data about how locust populations were building in space and time and an analysis of these trends, Chandrashekar added. With effective monitoring capabilities, including assessments of global climate and weather, India could manage locust populations to prevent plague-like situations.

Ecological impact of chemical pesticides

India has a predetermined list of chemical pesticides for locust control, according to the agriculture ministry’s Directorate of Plant Protection, Quarantine and Storage. These pesticides were sprayed on both land and crops.

“Pesticides like malathion and chlorpyrifos are fairly safe with low mammalian toxicity but they have to be used judiciously and only as the last resort,” Chandrashekara noted. These chemicals also bio-accumulate upwards in the food chain and have the potential to cause long-term damage.

Wildlife such as great Indian bustards, desert foxes, desert cats, laggar falcons and many other omnivore and carnivore species feed on locusts. This was why the use of chemicals is “harmful for the health of wildlife also,” Dookia said.

Farmers who grow organic crops in Rajasthan are also worried. For the organic certification, “farmers should not use pesticides for at least three years,” Dookia said.

‘One Health’ problem

“The other question is: Is the cure worse than the disease?” asked Vanak. “These are toxic substances and will lead to soil, water and air pollution. Some pesticides also contain carcinogenic substances and can therefore be lethal to humans.”

Pointing to the need to see issues concerning locust swarms through an ecological lens, Vanak pointed out that this was “a classic One Health problem because it potentially impacts environmental, animal and human health.”

One Health refers to a framework recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) to ensure better public health outcomes. Its areas of work include food safety, controlling zoonoses (diseases that can spread between animals and humans, like COVID-19) and combating antibiotic resistance.

Path ahead

“We are currently testing neem-based pesticides,” said Sunder Moorthi, assistant director for plant protection at the Locust Warning Organisation (LWO) at the Ministry of Agriculture. “Its success depends on the pesticide’s ability to fully repel locusts because if locusts halt in crop-filled areas, they will eat everything.”

According to the Food and Agriculture Organisation, non-chemical pesticides are “not the first tool of choice” when swarms are of high magnitude. And while wildlife feed on locusts, this, too, is not a solution that can match large-scale locust attacks because “any species that swarmed was meant to overwhelm predators,” Vanak explained.

The first step ought to be the recognition of the scale of potential crop damage and ascertaining if this could indeed turn into a food security issue in India. “If it is not, should we not just compensate farmers directly and look at this as a natural phenomenon?” Vanak asked. He added that the money being spent on seemingly excessive measures like the usage of drones and helicopters and the purchase of large amounts of pesticides could instead be allocated towards farmer compensation.

A thorough policy to ensure farmer compensation is the need of the hour, emphasised Dookia, agreeing with Vanak. “Farmers whose crops were damaged in locust attacks last year have still not received compensation,” he added.

The pest attacks were classified as natural disasters, Tomar noted in his Lok Sabha response, and accordingly, states could undertake relief operations under their State Disaster Response Fund. However, as of September 15, no state government had reported any relief measures for farmers affected by the locust attacks.

The mandate of organisations like LWO should be strengthened and broadened to include primary research into factors like locust swarming behaviour and biochemical mechanisms behind this, population modelling, etc., Chandrashekara suggested. “There should be ecological sense [in the functioning of organisations like LWO] and it cannot be reduced to monitoring locust populations and patrolling,” he added.

Based on such research, decisions regarding policy response could be made more appropriate like “when to use pesticides and how long to wait before using pesticides,” Chandrashekara noted. There were also innovations like incentivising the collection of locusts and using them as chicken feed like what Pakistan did this year. “Currently, there is no mechanism for solutions like this [using locusts as chicken feed],” Prakash said. “[Such solutions] are better than using chemicals,” he added.

About The Author

You may also like

With record breaking rain and heat, Uttarakhand reels under climate change impacts

Growing climate risks to India Inc call for a mindset shift, building resilience: Experts

Win for small island states as top maritime court calls GHG emissions a form of marine pollution

Philippines island faces risk of heavy rainfall which is now 50% more intense, along with deadly landslides : WWA report

Climate warming is altering food webs and carbon flow in high-latitude areas: Study