Much of the world is losing forests but adding plantations. While India is no different, the relative area under plantations and natural forests has been obscured. Visuals: Riddhi Tandon

As COP30 rolls out a tropical forest fund, how are India’s natural forests doing?

Part 4 of CarbonCopy’s forest series finds that even as the Forest Survey of India pegs India’s forest cover at 21.76%, satellite images show functional forest ecosystems cover just 1-10% of India’s land mass.

A conflict of interest has dominated India’s forest cover estimates for a long time. While the Union Ministry for Environment, Forests and Climate Change (MoEFCC) oversees the country’s forests, Dehradun-based Forest Survey of India (FSI) monitors their extent and condition. The FSI, however, is not an independent watchdog. It reports to the MoEFCC.

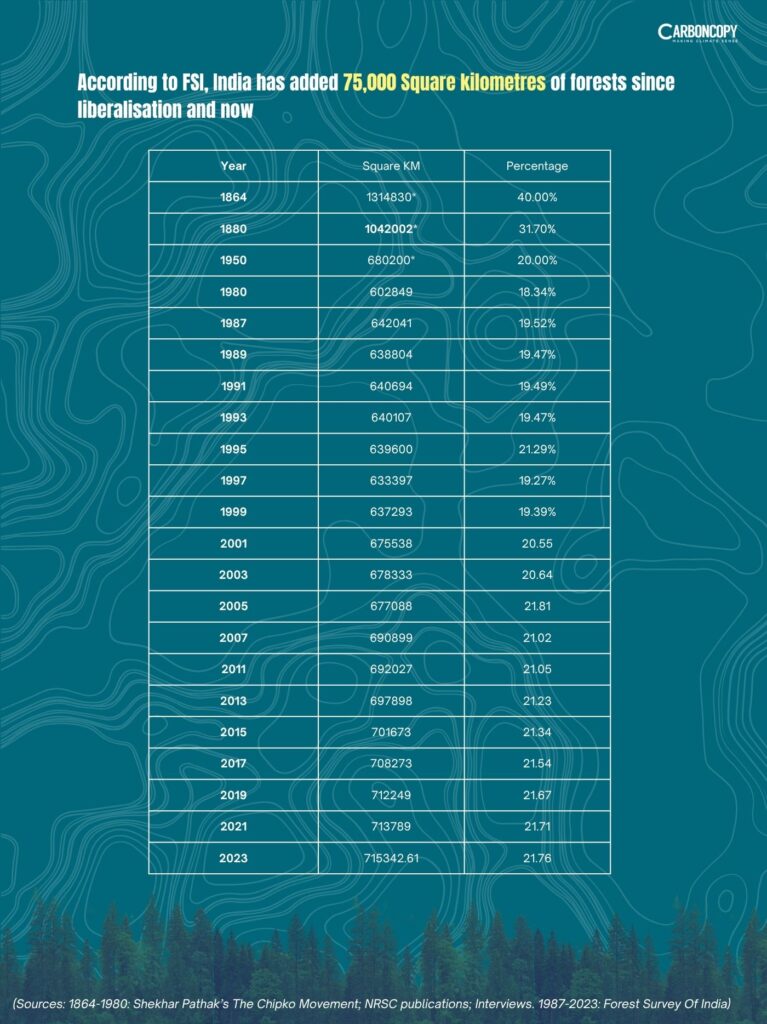

This arrangement is responsible for a puzzle in India’s forest numbers that has now lasted 38 years. Going by the FSI’s reports, India’s forest cover has grown from 642,401 square kilometres in 1987 to 715,342.61 square kilometres in 2023, a jump of 73,301 square kilometres. “India features in the list of top ten countries in terms of forest area,” adds the FSI’s 2023 report. “India also figures at 3rd rank in the list of top 10 countries with positive net change in forest area.”

These numbers and claims, though, feel counter-intuitive. Over the past 40 years, India’s population has almost doubled. Its people’s aspirations have risen. In areas abutting forests, both processes have translated into rising pressure on forests. A large question lies here.

Much of the world is losing forests but adding plantations. While India is no different, the relative area under plantations and natural forests has been obscured.

The costs of this veil are starting to become apparent.

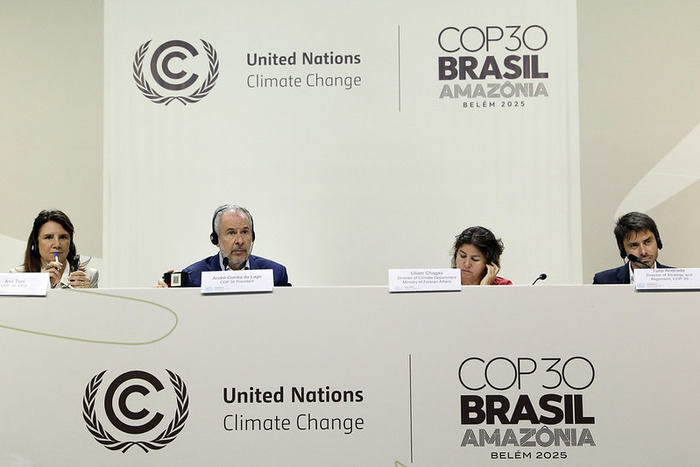

At COP30, Brazil has proposed the Tropical Forest Forever Facility (TFFF), a $125 billion trust fund comprising $25 billion from countries and the rest mobilised from the private sector, which will then be invested to generate $4 billion or so annually. This sum, nearly thrice as much as the money currently flowing into the protection of tropical forests, will flow to 74 countries with tropical forests. As this report gets written, TFFF has already received pledges for $5.5 billion from countries and India has joined the fund as an observer.

With climate change gathering pace, one waits to see if the fund will grow in size – and the quantum of money it will direct to these 74 countries. The amount of money countries can accrue, however, hinges on the quantum of their tropical forests.

That said, TFFF is not the only reason why India should care about its forests. Forests make India habitable. Not only is the country seeing a rise in human-wildlife conflict and a drop in elephant numbers, it also has previously perennial rivers drying up even in their upper reaches, all suggesting forest loss — and a looming crisis of human survival.

In all, a question needs to be asked. Keeping plantations out of forest cover calculations, what percentage of India is now under functional or old-growth or natural forest ecosystems?

Forest cover-up?

The paradox of India’s forest cover numbers has been out in the open for a while now.

As the second and third reports in this series have shown, India’s forest department is also wilfully failing to curb timber trafficking. With that, a clutch of commercially attractive trees like Khair (Acacia catechu) are vanishing from India’s forests, with attendant impacts on forest quality.

The MoEFCC has also been allegedly diluting India’s forest protection laws, making it easier for infrastructure and industrial projects to clear forests and site themselves in forestland. Between 2017 and 2020 alone, as environmental lawyer Ritwick Dutta’s Legal Initiative for Life and Environment claimed to have found, it denotified 726 square kilometres of forest. Close to half of this land was dense and moderately dense forests.

A clutch of researchers, too, have flagged contradictions between FSI assessments and local developments. Take Sonitpur, Assam. Between 1994 and 2001, as wildlife biologist MD Madhusudan has written, no less than 232.19 square kilometres of moist deciduous and other forest areas in this district close to the state’s border with Arunachal Pradesh were felled for cultivation. FSI’s reports, however, show a jump in its forest cover — up from 732 square kilometres (245, dense forests; 487, open forests) in 1999 to 1,054 square kilometres (471, dense forests; 683, open forests) in 2001.

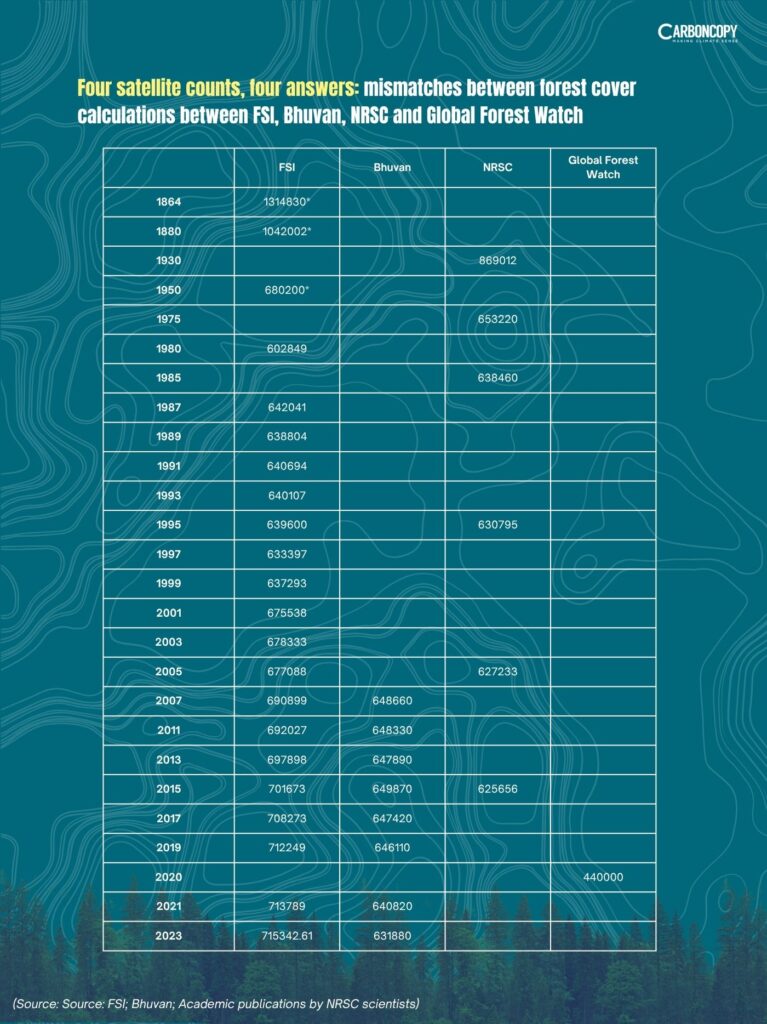

Each of these counter-arguments could be dismissed as a local aberration — while stressing that FSI’s reports capture the larger picture. Pan-India assessments from a sister state-owned agency, the National Remote Sensing Centre (NRSC), also say India’s forests are shrinking. “Over the past 20 years, while FSI data shows a 80,000 square kilometre increase in India’s forests, NRSC data shows a 15,000 square kilometre fall in Indian forests,” said Madhusudan.

Two questions — one procedural; the other ecological — lie here. The first, on the contradiction between FSI and NRSC numbers, is easily explained. FSI defines forests so expansively that plantations and public gardens get pulled into its forest cover calculations. With that, as scientists like Priya Davidar have written, even as India has cut forests, the country’s accretion of plantations has kept forest cover growing.

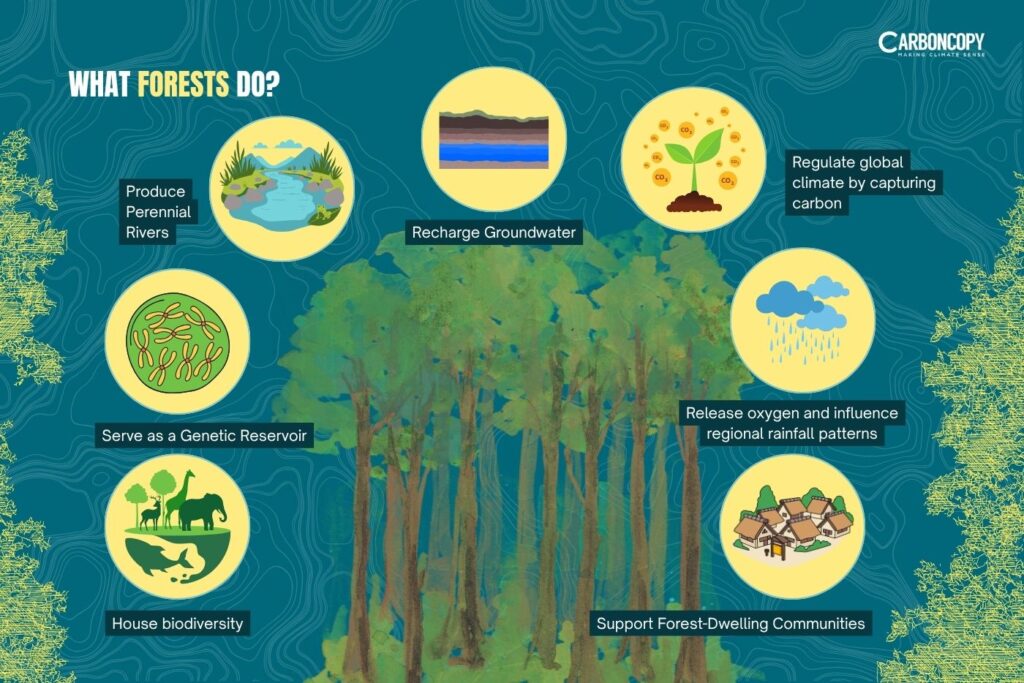

And yet, a collection of trees is not a forest. Evolving over millions of years, forests are complex ecosystems. Each comes with an unique assemblage of species — trees, ferns, animals, birds, insects, fungi and microbes — living off each other such that, as Barbara Kingsolver wrote in The Poisonwood Bible, the “forest eats itself and lives forever”. Apart from keeping the forest steady, as the box below shows, this latticework of species also stabilises global climate.

Plantations, in contrast, have a fraction of this diversity and so, perform a fraction of a forest’s ecological functions.

How to boost a forest

On the face of things, counting India’s forest cover should be easy.

All trees and plant species, given their biochemical and physiological nature, carry subtle differences in pigments like chlorophyll (which absorbs light in the blue and red parts of the spectrum, but reflects green). When studied from a satellite, these differences show up as unique signatures from each species and forest type per the spectrum each absorbs and reflects.

With precautions, like ground verification of satellite images; and not taking satellite scans only during rains, satellites can gauge the extent of crops, trees and forest types. Not only does India have access to such satellite data and imaging knowhow, the country’s forest department physically inspects forests — be it while preparing working plans or patrolling. It should be easy, ergo, for the FSI to club ground information with satellite images to produce its biennial snapshots of India’s forest health. And yet, looking for disaggregated data on forests and plantations in its reports is a fruitless exercise.

The reasons run deep. FSI, for one, interprets the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO)’s forest definition so expansively that plantations and public gardens qualify as forests.

Defining forests as “Land spanning more than 0.5 hectares with trees higher than 5 metres and a canopy cover of more than 10 percent”, FAO excludes “tree stands in agricultural production systems, such as fruit tree plantations, oil palm plantations, olive orchards and agroforestry systems” from its definition of forest cover. FSI, however, says: “All tree stands with canopy density over 10% and having an extent of more than one hectare, including tree orchards, bamboo, palms etc within recorded forests, on other government lands, private, community or institutional lands are included in the assessment of forest cover.”

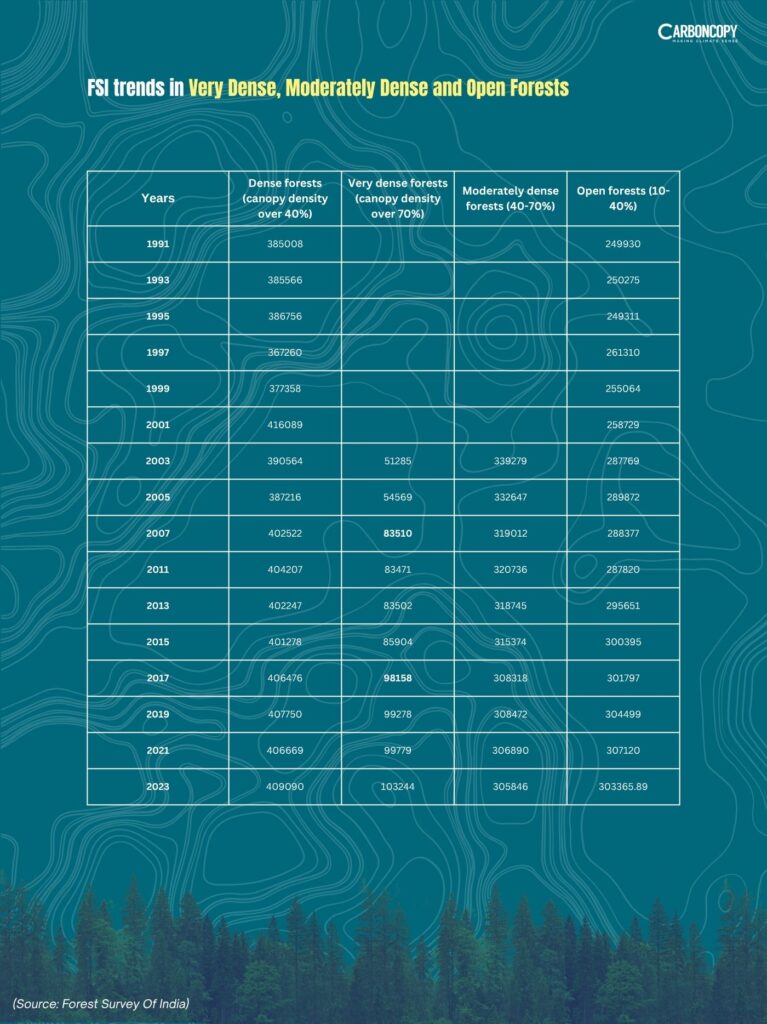

Thereafter, it has leveraged this (re)definition by not classifying forests by type (say, tropical evergreens or semi-evergreens) but by density (very dense, moderately dense and open). The fallouts are consequential. Even when the natural forest is cut and replaced by plantations, the focus on density lets FSI continue counting the land as a forest, alluding, at the most, to a change in forest density. See the chart below.

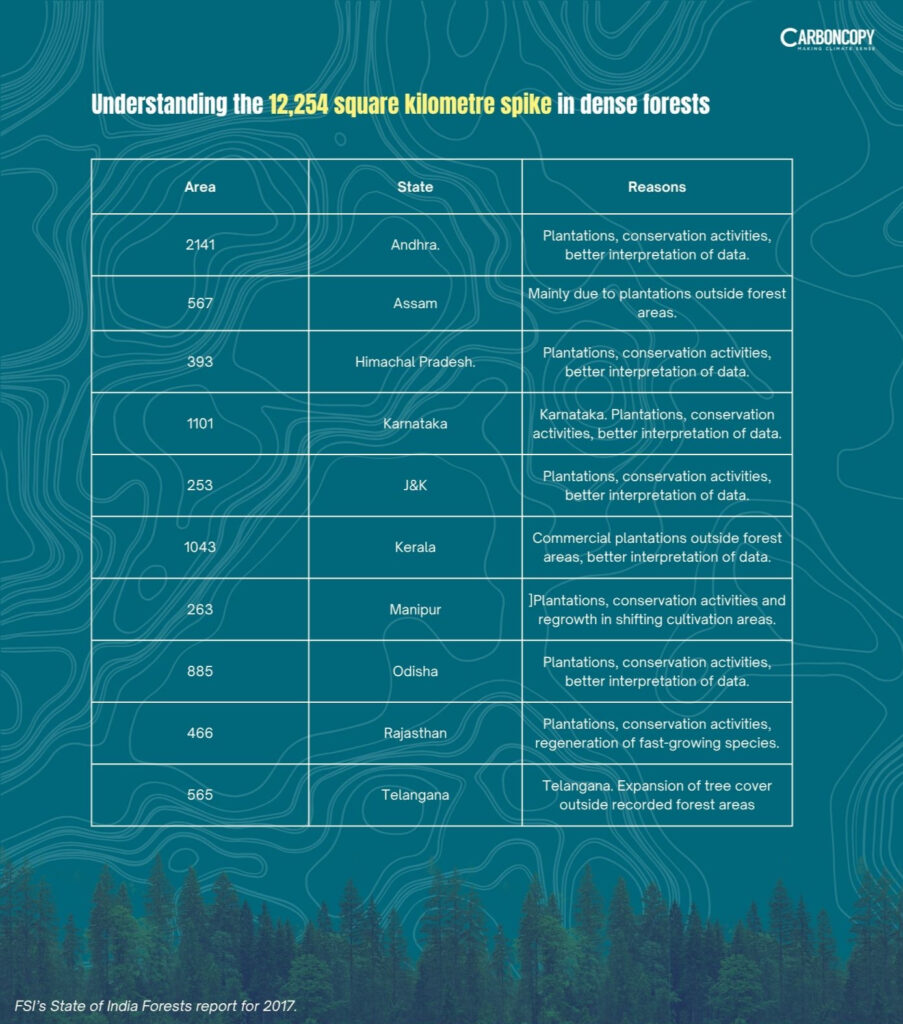

Going by the FSI’s numbers, very dense forests jumped discontinuously twice. First in 2007, mainly due to a change in mapping scale from 1:250,000 (25ha) to 1:50,000 (1ha), which permitted “the inclusion of smaller patches of forest cover up to 1 ha”. Then comes the jump in 2017 when land under dense forests spikes by nearly-13,000 square kilometres. While explaining that, FSI’s report lists plantations.

Apart from conflating natural forests and plantations, FSI has also muddied waters by tweaking its methodology. Its decision to change the minimum mappable area from 1:250,000 to 1:50,000 helped it count smaller forest patches, but also made it harder to compare newer reports with earlier ones. Compounding matters, as Madhusudan wrote, FSI reports “don’t just report forest cover for a new assessment year, but often go back and tweak forest cover values of previous years”.

In the past, as Parth Sarathi Roy, the now-retired director of Indian Institute of Remote Sensing told CarbonCopy, it has also added recorded forest area (land recorded as forestlands on departmental maps even if no forest stands there) to satellite images and included Prosopis juliflora, an invasive species, in its scrub forest estimates. Working on this report, CarbonCopy wrote to FSI asking it to explain these decisions. This article will be updated when it responds.

In the meantime, though, forests cannot be reimagined to suit administrative requirements. “In Assam, Hoolock Gibbons sitting in forest trees look out at tea plantations,” Madhusudan had said. “Even if the FSI calls them forests, the Gibbons cannot live there.”

What percentage of India is covered by natural forests?

India’s history of forest mapping through satellites is a tale of two organisations starting together, but then taking their own paths. It’s a tale that starts in 1980, a time when India was seeing protests against the proposed dam at Silent Valley. The Chipko movement against tree-felling was underway in the Garhwal and Kumaon Himalayas as well. Against this backdrop, then-Prime Minister Indira Gandhi asked for an estimate of India’s forest cover. That first assessment was jointly produced by FSI and the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO).

In the years that followed, the two organisations struck out on their own. FSI began producing forest assessments for the MoEFCC. Through centres like Hyderabad-based National Remote Sensing Centre (NRSC), ISRO, too, continued with its own land and forest mapping, providing its information to other government departments.

Working on this report, CarbonCopy started with NRSC’s Bhuvan database. We took the 250m database, which presents pan-India numbers. In this database, there are five categories of forests — deciduous woodlands; littoral/swamp/mangroves; shifting cultivation; evergreen/semi-evergreen; and degraded woodland.

Since our question is about the current expanse of natural forests, this report brought deciduous woodlands, littoral/swamp/mangroves and evergreen/semi-evergreen forests into its calculations.

When placed alongside FSI numbers, one sees a rising divergence as FSI’s estimates rise while those of Bhuvan drop. This contradiction has to be taken seriously. “Unlike the FSI, which is accountable only to the MoEFCC, NRSC is accountable to many more government departments,” Madhusudan had said. For this reason, it is less likely to bias its numbers towards a particular client, he added.

Other studies have yielded yet lower numbers for India’s forest cover. In 2015, NRSC scientists Sudhakar Reddy, CS Jha, PG Diwakar and VK Dadhwal published a paper titled Nationwide classification of forest types of India using remote sensing and GIS. It categorised India’s forests into five types (tropical moist forests; tropical dry forests; subtropical forests; temperate forests; and subalpine forests) and pegged India’s forest cover at 625,565 square kilometres in 2015. And then, there is Global Forest Watch. By 2020, it says, natural forests covered no more than 440,000 square kilometres — or 15% of India’s landmass.

CarbonCopy has written to the FSI asking it to comment on the contradiction between its numbers and those of NRSC and Global Forest Watch. This article will be updated when they respond. For now, though, even the Bhuvan and Global Forest Watch numbers constitute an upper range on what India’s natural forest cover might be.

A question about Intact Forest Ecosystems

TFFF seeks to support functional forest ecosystems. To stay ecologically viable, India, too, needs fairly large stretches of contiguous forest ecosystems that can perform all their environmental functions. For both these reasons, the question Indians have to ask is not about aggregate forest cover, but about intact forest ecosystems.

The second part of this series had described Uttar Pradesh’s Suhelwa Wildlife Sanctuary as an empty forest. “Close to 25 years have passed since the park last had a breeding population of tigers,” CarbonCopy had written. “Moving through the forest, one sees trees but hears little birdsong.”

The reasons are familiar enough. Illicit felling of timber created conditions for invasives like lantana to take root in the forest. With that, disturbed by human activity and not finding enough food, both deer and big cats have moved out. “This was supposed to be a tiger reserve,” Niharika Singh, a local activist and a former member of UP’s State Wildlife Board had told CarbonCopy. “But now, not even a khargosh (hare) is seen here.”

Suhelwa is far from an outlier. About 10 years ago, travelling in the forests of southern Chhattisgarh just after Salva Judum founder Mahendra Karma was killed, this reporter had been struck by how silent those forests were. “Even in the Jarawa reserve, Garjan and Padauk are being logged,” Roy had said. Elsewhere in the country, as in the vicinity of Hasdeo Arand and Tadoba, mines have come up close to forests. “Across India, as with the world, forests are turning into isolated fragments with impaired functional ecological capabilities,” a former professor at Dehradun’s Wildlife Institute of India told CarbonCopy. “This has resulted in a reduction of the ecosystem services they provide.”

The difference is material. As Roy and his co-authors reported in a 2013 paper titled Forest Fragmentation in India, intact forests house far more biodiversity than fragmented areas. While intact forest areas had a total of 6,660 species, highly fragmented areas had no more than 1,125. Their capacity to provide the ecological services mentioned above shrinks as well. The Hoolock Gibbons near Jorhat, for instance, now have just the 20 square kilometres that comprise the Hoollongapar Gibbon Sanctuary. It is what they have to survive in — even though the small area caps their numbers.

For this reason, anyone trying to quantify the current expanse of functional forest ecosystems, those forests working as before, has to exclude fragments as well.

How large should an intact forest ecosystem be? The answer depends on the conservation goal. To house a squirrel, a one hectare patch might be enough. For an elephant, a much larger range will be needed. For other ecological services, like producing a river, the answer changes again.

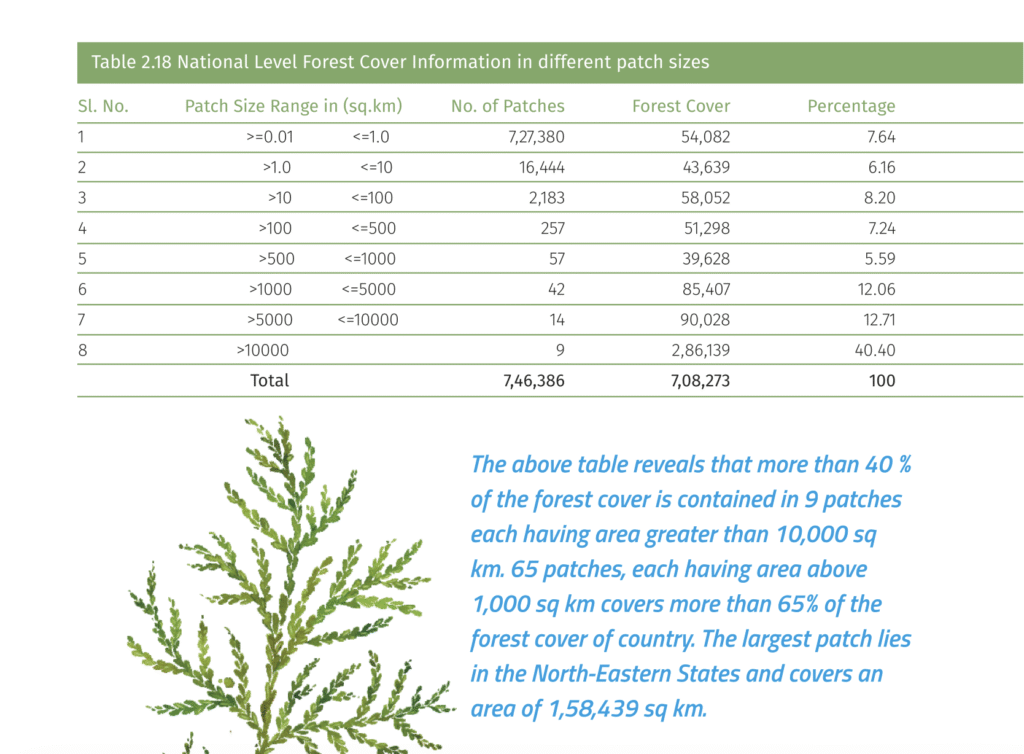

In India, data on forest sizes has been hard to come by. One FSI report, the one for 2017, has some numbers. However, the ones for 2019, 2021, 2023 don’t. Even so, the 2017 report makes for an eye-opening read.

Going by these numbers, fragments less than 100 square kilometres (10 km by 10 km) accounted for 22% of India’s forest cover at the time data was collected for the 2017 report. Patches between 100-1,000 square kilometres accounted for another 12%. To put that in perspective, if a park needs 20 breeding tigress to keep the population genetically viable, it will need at least 800-1,200 square kilometres of inviolable space.

In other words, between 2015 and 2017, forest patches bigger than 1,000 square kilometres covered 461,574 square kilometres of India’s geographical area (14% forest cover, in essence). Even this number, however, is an over-estimate. The FSI, as data shows, mixes up plantation and forest numbers.

In Forest Fragmentation in India, Roy et al say almost half of India’s forested areas were intact. Going by Bhuvan data, that works out to 323,945 square kilometres (about 10% of India’s geographical area) in 2013, when their paper was published. The caveat is, 12 years have passed since and India has seen both human pressure and large projects sited on forestlands rise since.

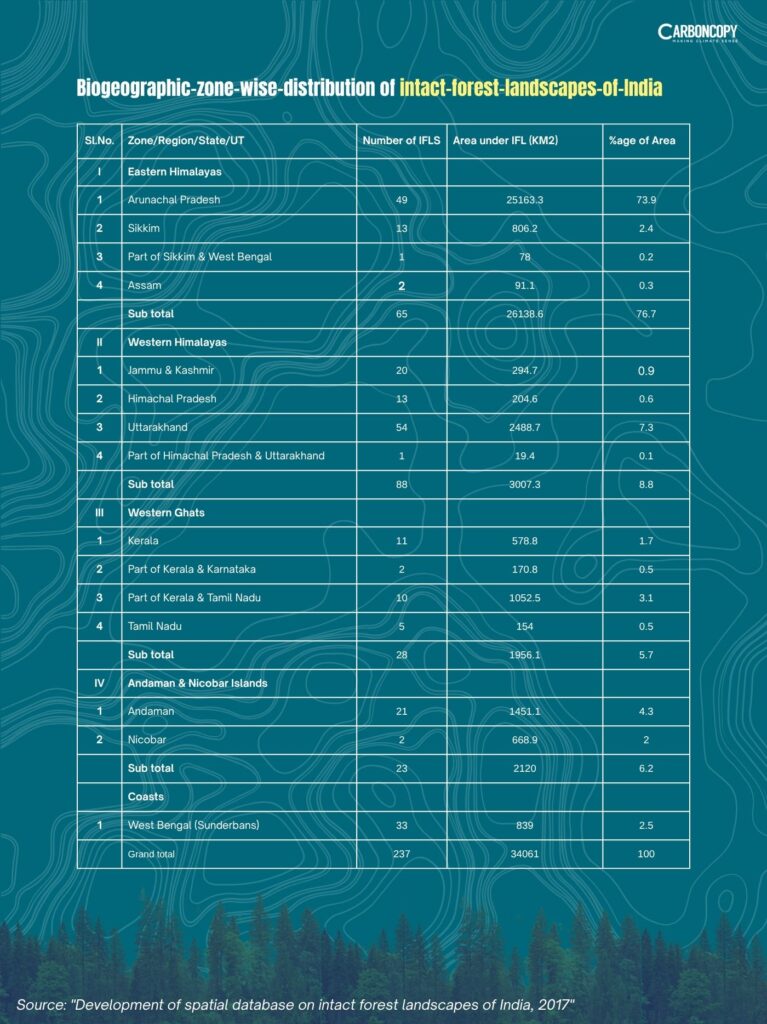

Another paper, titled Development of spatial database on intact forest landscapes of India, reaches a harsher conclusion. Defining intact forest ecosystems as those showing “no signs of forest change, settlements, roads and land clearing during the last eight decades”, it also pegged the minimum size at 10 square kilometres. Here is what they found: “Current intact forest landscapes of India (consisting) of blocks larger than 10 km2 covers an area of 34,061 (square kilometres).”

This works out to just 1% of India’s total geographical area. Most of these patches, says the paper, are in the eastern Himalayas, followed by the Western Himalayas, Andaman and Nicobar Islands and then, the Western Ghats.

The rest of the country’s forests, then, are relatively mixed-use landscapes straddling a continuum from slightly used to heavily degraded. This paper, too, however, was published in 2016 and its numbers are outdated now. Working on this report, CarbonCopy’s efforts to meet NRSC scientists for an updated assessment were unsuccessful.

Given that regeneration is not counted while measuring intact forest ecosystems — WRI’s methodology, for instance, assumes that once lost, intactness cannot be regained — India needs to ask itself a very urgent question. If, by 2016, intact forest ecosystems covered no more than 1% of the country’s geographical area, what is that number today? Even taking a more expansive definition for forest cover, as inviolable areas are hard to come by in a country like India where millions depend on forest produce, forest patches (including plantations, though) bigger than 1,000 square kilometres covered just 14% of India’s geographical area by 2017. How much of India do they cover now? CarbonCopy posed this question to both FSI and NRSC. This article will be updated when they respond.

Hardwired into this question is a warning about India’s ecological future. Intact forest landscapes are so because of their distance from dense human populations and/or extractive industries and/or industrial development. “The highest area of IFL [Intact Forest Landscape] was found in elevation zone of 2,500-3,000m followed by 2,000-2,500m and 1,500-2,000m,” says the spatial database paper. “No intact forest landscapes of larger than 10 (square kilometres) were found in arid, semi-arid, Deccan, north-east and Gangetic plains.”

The final part of this series will look at the consequences that follow.

Heavy rain hit Tamil Nadu and Kerala between November 13 and 18, with thunderstorms and squally winds over the southwest Bay of Bengal early in the week. Photo: Canva

Rains Lash South India as Early Cold Wave Grips Central and Northern India

India saw a sharp split in weather this week with the IMD issuing warnings for both heavy rain in the south and an early cold wave in central India. The southern states stayed busy with rain and thunderstorms, especially across Tamil Nadu, Kerala, coastal Andhra Pradesh, and parts of Karnataka. Heavy rain hit Tamil Nadu and Kerala between November 13 and 18, with thunderstorms and squally winds over the southwest Bay of Bengal early in the week.

Meanwhile, central and northern states slipped into an early cold wave. West and East Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, and parts of Rajasthan recorded below-normal temperatures and isolated severe cold wave conditions through November 15. Mumbai also felt the chills. Santacruz recorded a minimum of 19.6°C, 2.3°C below normal, and Colaba dipped to 22.4°C, alongside rising pollution levels.

Northeast India experienced shallow fog and a slight dip in temperatures, while most other regions remained dry and stable.

Climate change has driven dengue into a year-round threat in Goa, say health experts

Dengue is no longer confined to the monsoon months in Goa and has become a year-round threat, The Times of India reported, citing Dr Kalpana Mahatme, who oversees the state’s vector-borne disease control programme. She said unseasonal rain driven by climate change, along with a steady inflow of tourists and migrant labour, is keeping transmission active beyond the usual season.

Health centres have been told to watch construction sites and migrant settlements, as the Aedes mosquito is already established in the state. Residents have been urged to prevent any stagnant water and get tested at the first sign of fever. Goa recorded 11 dengue cases in October and 84 this year, down from 511 last year.

Scientists undertake expedition to study Arunachal’s glaciers

A week-long scientific expedition to study how Himalayan glaciers are responding to climate change began last week in Arunachal Pradesh’s Mago Chu basin beneath Gorichen Mountain. The fourth Khangri glacier mission is being led by glaciologist Dr Parmanand Sharma and jointly organised by the Centre for Earth Sciences & Himalayan Studies and the National Centre for Polar & Ocean Research. Despite Arunachal’s 161 glaciers across four major basins, almost none have undergone long-term field monitoring, making the region a major blind spot in India’s cryosphere research. The team will measure glacier mass balance, movement, and the evolution of glacial lakes, including potential GLOF risks. Findings are expected to improve understanding of climate impacts and the Brahmaputra basin’s long-term water security.

Climate change and fertiliser misuse depleting India’s soil carbon, ICAR study finds

A major ICAR study found that unscientific fertiliser use and climate change are driving a decline in soil organic carbon across India’s arable land. The six-year project, coordinated by the Indian Institute of Soil Science and based on more than 2.5 lakh soil samples from 620 districts, shows that organic carbon levels are tightly linked to temperature, rainfall and elevation.

Warmer regions such as Rajasthan and Telangana recorded lower carbon levels, while higher elevations showed richer soils. Cropping patterns also played a role. Rice- and pulse-based systems maintained higher carbon than wheat and coarse grains. States with imbalanced fertiliser use, including Punjab, Haryana and western Uttar Pradesh, saw sharper declines. The findings warn that rising temperatures could further deplete soil carbon and worsen land degradation.

2025 on track to be one of the hottest years ever, warns UN

The UN warned that 2025 is on track to be one of the hottest years ever recorded, driven by exceptional temperatures and record-high greenhouse gas concentrations. While it will not surpass 2024, it is expected to rank second or third, extending a decade-long streak of unprecedented warming.

The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) said the first eight months of 2025 were already 1.42°C above pre-industrial levels, and rising emissions mean the world is veering off the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C pathway. UN officials described missing the target as a moral failure, but stressed that temperatures could still be brought back down by century’s end with rapid action. The report also highlighted shrinking Arctic and Antarctic sea ice and escalating extreme weather impacts worldwide.

Solar geoengineering could reduce crop nutrition, warns study

A new study in Environmental Research Letters finds that cooling the planet by injecting sulfur dioxide into the stratosphere — a proposed solar geoengineering method known as stratospheric aerosol intervention (SAI) — could lower the protein content of major global crops. Researchers at Rutgers University used climate and crop models to examine how SAI would affect corn, rice, wheat and soybeans. They found that while higher CO₂ levels reduce crop protein and higher temperatures tend to increase it, SAI would prevent warming and allow the CO₂ effect to dominate, resulting in lower protein levels. The biggest declines would hit regions already facing malnutrition. The authors stress that more field research is needed to fully understand SAI’s risks before any decisions are made.

Scientists criticise Bill Gates’s climate memo

Bill Gates’s new memo on the climate crisis drew sharp criticism from climate scientists, who said it relied on straw man arguments and false binaries, reported The Guardian. In the 17-page note, Gates argued that global warming would not cause humanity’s demise and urged a shift from cutting emissions toward reducing poverty. Scientists countered that no one had predicted human extinction. The concern was rising suffering with every fraction of a degree of warming. Researchers like Zeke Hausfather rejected Gates’s claim that climate spending reduced aid budgets, noting it was not a zero-sum tradeoff. Others said the memo downplayed the scale of climate impacts and misrepresented current science. The debate unfolded just days before the COP30 negotiations in Brazil.

Scientists warn warming seas are supercharging deadly typhoons like Kalmaegi

Typhoon Kalmaegi, the year’s deadliest storm, tore through the Philippines before hitting central Vietnam, killing more than 190 people across both countries and leaving widespread destruction. Scientists warned that such extreme events are becoming more intense as rising global temperatures warm sea surfaces in the western Pacific and South China Sea. Warmer waters load storms with more moisture and energy, increasing the likelihood of heavier rain and stronger winds, even if overall cyclone numbers are not rising.

Researchers noted a clear uptick in the most intense storms and rapid intensification episodes, alongside back-to-back systems that compound damage. The storm’s arrival coincided with global climate talks in Brazil, underscoring growing risks for low-lying regions in Southeast Asia.

President André Corrêa do Lago urged the world to look to the Global South for solutions. Photo: Flickr/Agência Brasil

COP30 Kicks Off With Hard Talks on Money, Adaptation and Global South Leadership

COP30 opened in Belém with a clear message from the Brazilian presidency: this is an implementation COP, with adaptation at its centre. More than 47,000 delegates from 195 countries arrived as President André Corrêa do Lago urged the world to look to the Global South for solutions, given the US’s absence and Europe’s diluted climate ambition. India set the tone for developing nations, forcefully emphasising equity and Common but Differentiated Responsibilities (CBDR) while demanding clarity on climate finance, a stronger Global Goal on Adaptation, and a universally agreed definition of climate funding.

Negotiations got underway quickly, with the presidency pushing through the agenda on Day 1 to avoid procedural delays. Contentious issues include unilateral trade measures, NDC updates, Biennial Transparency Reports, and Article 9.1 on finance obligations. The first two days also saw protests inside the venue, prompting UNFCCC chief Simon Stiell to criticise security failures and call for better conditions amid extreme heat and flooding.

A major development came with the launch of the Tropical Forest Forever Facility (TFFF), which secured more than $5.5 billion in initial pledges. Norway committed $3 billion, Brazil and Indonesia $1 billion each, and smaller contributions came from France, the Netherlands and Portugal. The fund — the first climate finance mechanism led by the Global South — will pay forest countries $4 per hectare annually to keep forests standing, with at least 20% of payments guaranteed for Indigenous and local communities.

On finance, the IHLEG report dominated conversations, arguing emerging economies need $3.2 trillion annually until 2035 and urging an integrated finance agenda anchored in public grants, private capital, carbon markets, South–South cooperation, and MDB reform. The report shifts greater responsibility onto developing countries to craft credible, country-led investment plans capable of attracting large-scale capital.

WMO Warns World Is Set to Overshoot 1.5°C as 2025 Nears Record Heat

The world is now all but certain to overshoot the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C limit, the World Meteorological Organisation warned at COP30 in Belém, as new data showed 2025 is on track to be the second or third warmest year on record. The WMO’s State of the Global Climate Update found that 2015–2025 will be the hottest 11-year stretch ever observed, with 2024 becoming the first year to exceed 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels for an entire year.

Global temperatures from January to August 2025 averaged 1.42°C above the pre-industrial baseline, reflecting a shift from El Niño to neutral or La Niña conditions. UN secretary-general António Guterres said each year above 1.5°C will deepen inequalities, damage economies and leave irreversible impacts unless governments act at “speed and scale.”

Stronger NDCs could slow warming, but not enough: UNEP report

The UNEP Emissions Gap Report warned that the world remains far off track to meet the Paris Agreement goals, with global warming still headed for 2.3–2.5°C even if all current NDCs are fully implemented. Without stronger action, existing policies would push temperatures up to 2.8°C. UNEP said the slight improvement over last year is largely due to methodological updates, while the upcoming US withdrawal from the Paris Agreement will cancel out much of that gain. Crucially, a temporary overshoot of 1.5°C is now unavoidable, driven by record-high emissions that rose to 57.7 GtCO2e in 2024. India, China and Indonesia saw the biggest increases. UN secretary-general António Guterres urged COP30 to deliver a credible plan to close both the ambition and finance gaps.

Climate Finance Is Ignoring Health: New Report

A new report released ahead of COP30 warns that global climate finance is failing to protect public health, even as climate-driven illnesses, heat stress and disease outbreaks surge worldwide. The Adelphi study finds that only 0.5% of multilateral climate finance — just $173 million since 2004 — has supported health adaptation, despite health priorities appearing in 87% of National Adaptation Plans. South Asia, which is projected to face 18% of future climate-related health impacts, has received no country-specific health adaptation funding. India, already strained by heatwaves, vector-borne diseases and extreme weather, will need more than $2.4 trillion by 2050 to manage climate risks.The report urges grant-based finance, country-led priorities and stronger climate–health coordination to prevent millions of avoidable deaths.

Parents, environmental activists, came together and staged a protest at India Gate on Nov. 9 against the worsening air quality in Delhi. Photo: Paridhi Choudhary

Parents, Activists Protests at India Gate as Air Turns Toxic

Parents, environmental activists, came together and staged a protest at India Gate on Nov. 9 against the worsening air quality in Delhi. The protestors demanded urgent government action to ensure clean air, reported The Hindu.

Several protestors were later detained for assembling without permission. The air quality in Delhi has turned severe for the third consecutive day. The air quality bulletin issued by the Central Pollution Control Board showed an AQI reading of 404 on November 13.

Indians Living in City Breathe 190 Plastic Particles

A research found “new air pollutant”- inhalable microplastics. These microplastics are small enough to slip deep into the human lungs. The New Indian Express reported that this polymer dust is not freely floating into the air that we breathe.

The air particles were collected from bustling marketplaces in Kolkata, Delhi, Mumbai, and Chennai. According to the report, a person breathing in a busy market could inhale around 190 plastic particles in 8 hrs.

Punjab Pollution Board Calls 14 Major Brands for Contributing to Plastic Waste

The Punjab Pollution Control Board (PPCB) called 14 major brands after a recent audit found that they were contributing to pollution in the state. The PPCB has demanded clear actions from these brands to curb plastic pollution, reported Times of India.

The PPCB chairperson said that the brands cannot shift responsibility and sought accountability and action from them. This action was based on the “Plastic Waste Brand Audit 2025” and the report found that out of 11,880 pieces of branded plastic packaging recovered, these 14 brands were linked to 59% of the waste that cannot be recycled.

Greece’s Azure Waters Polluted Due to Growing Microplastic Pollution

Overtourism and heavy maritime traffic across the Mediterranean is contributing to a rise in the pollution in Greece’s seas.Greek scientists had sent mussels-filter feeding organisms- on the sea floor to detect microplastics, reported Reuters.

The scientists found that the entire mediterranean sea has become a hotspot for microplastics. They said that concentrations are still not high enough to be harmful to humans but microplastics are found in every single species the team had analysed.

Low-Income Neighborhoods Face Worst Air Pollution in England and Wales

Low-Income areas in England and Wales face the worst air pollution despite the decrease in air pollution there, a study found. Experts have called this an environmental injustice, reported the Guardian.

Experts said that the impact of this will be the most on people of colour and these neighborhoods tend to be in London and Manchester.

Non-fossil fuels sources including wind, solar, small hydro, and nuclear, in 2025 powered one-third of India’s total energy output. Photo: Canva

Non-Fossil Fuels Generates One-Third of India’s Electricity in 2025

Non-fossil fuels sources including wind, solar, small hydro, and nuclear, in 2025 powered one-third of India’s total energy output. The first half of the current fiscal year witnessed a marked rise in its share compared to the same period last year, reported ET Energyworld.

In April-September, 2025, India’s non-fossil fuel domestic generation, excluding thermal and Bhutan imports, stood at 301.3 billion units, accounting for 31.3% of the country’s total electricity.

India to Remain a Major Export Hub for Key Wind Power Components till 2030

India will remain a key export hub for inshore wind components, underscoring the country’s expanding role in the global renewable energy supply chain, reported ET Energyworld.

India currently has more than 20GW of wind turbine manufacturing capacity catering to both domestic demand and export markets. Indian manufacturers account for about 12 per cent of the global nacelle manufacturing capacity, contributing roughly 20GW out of a global total exceeding 165GW.

India Issues Over 2,000 MW of RE Tenders in October

India has issued 2,330 MW of renewable energy tenders in October 2025 under the project development category. Meanwhile, over 3,600MW are allocated to various developers, reported Asian power.

According to the latest data, the tenders issued last month including SECI, invited bids for a 1,200MW/4,800 MW-hour peak power supply tender, consisting of firm and dispatchable renewable energy from ISTS-connected RE projects with co-located storage systems.

JSW Energy Boosts Renewable Capacity, Reaches 13.3 GW Total Installed Capacity

JSW Energy expanded its renewable energy capacity with 13.3 GW of operational capacity and brought its total capacity to 13,295 MW, with renewable energy now contributing to 57% of the overall capacity, reported ScanX News.

The company, however, is also facing legal challenges as the Supreme Court denied its request to pause an APTEL decision supporting CERC’s ruling on tariff for its 1000MW battery energy storage system request.

Germany Signs €50m Debt Swap for Renewable Energy Grid Connection with Egypt

Germany and Egypt signed €50m debt swap agreements to finance projects to connect two wind power stations to the national grid, reported Daily News Report. The head of Egyption Electricity Transmission Company (EETC) signed the agreement with an official from German development bank KfW.

The ministry said the agreement is part of the German government’s support for Egypt’s electricity and renewable energy sector, and its efforts to reduce carbon emissions and transition to clean energy.

Technology&Innovation

The decline in volume reflected the shrinking market share which has been overtaken by legacy giants like Bajaj Auto and TVS Motors. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Ola Cuts FY26 Revenue Forecast as Focus Shift to Profitability

Ola Electric cuts its fiscal 26 overall revenue target, while maintaining forecasts for the core automotive business as it shifts the focus to profitability over volumes, reported Reuters. Shares of the company fell 5% post announcement which were down 0.8% prior to the announcement.

The decline in volume reflected the shrinking market share which has been overtaken by legacy giants like Bajaj Auto and TVS Motors.

Lucid Cuts Production Forecast Amid Supply and Production Constraints

Lucid cut down in its 2025 production forecast to 18,000 vehicles as it grapples with industry-wide supply and production constraints, reported Reuters.

The EV maker also suffered a blow at the stock market as shares fell 3% in extended training after it reported revenue for the third quarter below the analyst estimates and bigger than expected loss despite the jump in deliveries.

Tesla’s Co-Founder Start Critical Minerals Plant Production as EV Market Sets to Decline

Tesla’s co-founder JB Straubel opened a new facility for their battery recycling venture, Redwood Materials that will supply critical minerals, reported Bloomberg. Tesla is facing an expected slowdown in the EV segment.

Redwood has also started a new unit called Redwood energy that turns degraded EV batteries into grid-scale energy storage systems, and raised a $350 million Series E to speed up energy storage deployment.

JSW in Talks with Japan, South Korea Firms to Cut Reliance on China for Battery

JSW group is in talks with Japanese and South Korean firms for battery cell manufacturing in India as it looks to reduce its reliance on China, reported ET.

The conglomerate is looking to safeguard its supply chains for its new energy vehicle business. Discussions are expected to conclude by March, with the joint venture potentially serving energy storage and renewable integration.

MoEving to lease 700 small Tata Motors’ electric CV for Last-Mile Deliveries

MoEving, electric mobility solution provider has partnered with Tata Motors’ to 700 small electric commercial vehicles (CVs) that will be deployed for the last mile deliveries across 10 cities, reported Economic Times.

This move will help the e-commerce, logistics, and FMCG sectors’ growth and their business model will make electric vehicles deployment scalable and cost-effective.

Oil prices fell more than $2 a barrel as OPEC body predicts supply demand balance in 2026 contrasting with earlier predictions of a supply deficit. Photo: Canva

OPEC Predicts 2026 Supply-Demand Balance, Leading to Another Drop in Oil Prices

Oil prices fell more than $2 a barrel as OPEC body predicts supply demand balance in 2026 contrasting with earlier predictions of a supply deficit, reported Reuters.

The US government reopening is expected to boost economic activity and crude oil demand. The US is expected to release its outlook soon.

India Will Need to Produce 130 Million Litres of SAF by 2027 to Decarbonise Aviation Sector

India will need to produce 130 million litres of Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) annually by 2027 for a 1% blend and 720 million litres by 2030 for a 5% blend. This will help decarbonise the sector and establish the country as a global SAF producer, reported ET Energyworld.

The aviation sector accounts for about 2.5% of global CO2 emissions and without decarbonisation the share will rise to 20% by 2050.

Reliance Looking to Sell Middle Eastern Crude in Spot Market Amid Shift in Oil Sourcing

Reliance Industries is looking to sell Middle Eastern Crude, including Murban and Upper Zakum on the spot market, in an unusual move by the Indian refiner that’s normally a major buyer, reported Bloomberg.

Reliance has already sold a cargo of Iraqi Basrah Medium crude to a Greek buyer. Refiners in India are busy trying to diversify their supplies after Western sanctions made buying Russian oil more difficult and risky.

Rajgarh Villagers Protest Against Mining Projects Over Environmental Concerns

Thousands of tribals from over a dozen villages in Dharamjaigarh region of Chattisgarh’s Rajgarh district are camping outside the collector’s office demanding cancellation of an upcoming public hearing for a proposed private coal mining project, reported ET.

The Hasdeo-Rajgarh forest belt which faces mining pollution and human-elephant conflict has become a new flashpoint between industrial expansion and tribal rights.

US Adds 10 Critical Mineral to List to Reduce Reliance on China

The US administration has widened its critical mineral list, adding copper and coal to boost local output and reduce the reliance on foreign countries, especially China. The government will offer incentives for projects related to these minerals, reported Reuters.

Environmentalists have slammed this move stating that the administration was ignoring economics, violating the law, and opening the door for agencies to rubber-stamp the projects with insufficient protections for communities from pollution.

NTPC Begins Drilling India’s First CO2 Storage Well in Jharkhand, Launching Carbon Capture Efforts

NTPC Limited has begun drilling India’s first-ever carbon dioxide (CO2) storage well in the Pakri Barwadih coal mine in Jharkhand, launching the country’s carbon capture and storage efforts, reported ET Energyworld.

The borewell designed to reach a depth of around 1,200 metres aims to gather geological and reservoir data to enable safe and efficient long-term CO2 storage.