The implications of the escalation in border tensions between India and China last month were never going to be limited to security. Soon after the Indian Ministry of Power declared intentions to ban all power equipment imports from China, Indian power producers latched on to the recent clamour to boycott Chinese goods to angle for extensions in the implementation of environmental norms in thermal power plants, particularly with regards to the installation of Flue-gas desulfurization (FGD) technology to control toxic sulphur dioxide emissions.

In a letter written to the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) on July 1 the Association of Power Producers (APP) sought an extension of three years from the 2022 deadline to install the emission reducing technology. Their reasons? “The disruptions caused by the pandemic and a growing clamour for the boycott of Chinese goods in the aftermath of the recent clash between Indian and Chinese troops,” elaborates the letter. On July 7, the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce & Industry (FICCI) followed suit and wrote to the PMO seeking intervention for the immediate deadline for installation of emission control equipment at captive power plants for which the deadline was June 30, 2020.

An ongoing saga of excuses

These requests from industry did not come out of the blue. In fact, just weeks before the APP letter to the PMO, the Supreme Court summarily dismissed a petition by the body seeking extensions to the deadlines for meeting pollution norms for thermal power plants. The government notification mandating FGD technology issued to all TPPs in the country was issued in 2015 with the deadline set in 2017. Since then, the deadline has been extended to December 2022 in a staggered manner. Yet, we find that only 1% of the total coal power plant capacity has commissioned FGD technology till July 2020, casting serious doubts on whether the rest of the plants can meet the 2022 deadline. In the Delhi-NCR region, where TPPs were required to install the technology by the end of 2019, only one in 11 plants had managed to meet the deadline. So, are the latest requests for extensions justified?

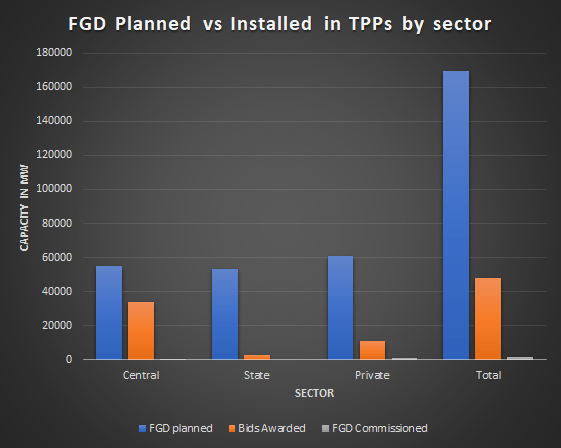

According to Sunil Dahiya, analyst at CREA, these latest explanations by industry fall flat upon scrutiny. “It’s a ridiculous and an unjustifiable argument to make,” Dahiya said. “For the majority of the capacity, the bids are yet to be awarded. If bids haven’t been awarded yet, then there cannot be any question of delay.” Bids have been awarded only for 46,300 MW (27%) capacity, and are still to be awarded for 1,22,857 MW (72%) capacity.

CEA’s figures on the status of FGD installation give Dahiya’s arguments further credence, especially considering that FGD installation typically takes at least two years after being bid out. Despite industry’s persistence that recent disruptions would force non-compliance of emission norms, it can clearly be seen that until July 2020, less than 20% of the required FGD installations had been bid out. For state units, the proportion of bid out projects is even more abysmal at just 5% with installations complete at none of the 53,225MW of thermal power plants.

“Since 2015, there have been several arguments that have been put forth by the APP, from a lack of space for the installations, to funding requirements and now a lack or scarcity of technology providers for FGD,” Dahiya said. Most of these have been debunked by the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, the courts and the CPCB, Dahiya said.

While setting the China argument straight, Dahiya said, “Companies like BHEL have the technology and can adapt them to our needs. China is not the only supplier. Besides, Aatmanirbhar Bharat initiative is all about producing locally. The only thing stopping pollution control technology installation is not funds or lack of tech supply, but lack of willingness”.

This sentiment was echoed by environmental lawyer Ritwick Dutta. “Recently, the MoEFCC exempted the requirement of trucks carrying coal to be covered in tarpaulin. This order was struck down by the NGT. But just a few days ago, the NTPC challenged the NGT order in the Supreme Court. Today, we have power companies who are not even willing to cover their trucks with tarpaulin because they say it will lead to a delay in loading and unloading of coal. There is no intention to comply.”

The burden of apathy

While the contribution of thermal power plants to air pollution has been beyond doubt, source-based attributions of specific elemental loads have only recently begun giving us a more granular picture. Professor SN Tripathi, a member of the Steering Committee of the National Clean Air Plan, and Head of Civil Engineering at IIT Kanpur, conducted a recent study to determine their contribution to overall pollution. His study selected sulphur, lead, selenium and arsenic to analyse sulphate composition in Delhi in the lockdown phase and before that.

“These 4 elements give a fair idea about source contribution from power plants to total PM2.5. This concentration of power plants to total PM2.5 has been in the range of 8pc, in Delhi’s air. After a significant drop, it came close to levels towards the end of the lockdown.”

According to a paper published in 2017 on the costs and benefits of FGD installation in Indian power plants, over 15,500 deaths annually are attributable to SO2 emissions from TPPs. The paper further elaborates that full coverage of FGDs in Indian power plants would reduce this burden by about 90%.

Is it all about the money?

While power producers continue spending several lakhs of rupees in legal fees, they simultaneously continue to complain about the high cost of retrofitting FGD technology. Power producers, in the past, have even petitioned the government to exempt producers with power purchase agreements (PPAs) signed before 2015 to be exempt from the additional costs of installing emission control technology under the “change in law” clause of their PPAs. This contention was put to rest by the Central Electricity Regulatory Commission (CERC) in 2018 when it dismissed a petition by Adani power against DISCOMs in Gujarat and Haryana. The CERC stated that since environmental norms that are sought to be implemented by the 2015 government notification had been specified in the Environment (Protection) Act of 1986, there is no question of any exemptions.

Studies though have suggested that concerns surrounding these costs may also be overblown. According to CEEW’s revised estimates based on new tenders issued, if all plants, including those identified for retirement in Central Electricity Authority’s National Electricity Plan, 2018, were to be retrofitted with PCT, it would cost ₹94,267 crore. If only eligible plants were included, the cost would fall to ₹80,587 crore. The more the retrofitting is delayed, however, the higher the costs will be as seen in the CEEW’s revised cost estimates, which have increased by 10% compared to their 2018 cost projections due to implementation delays.

The penalties charged for non-compliance on their own seem significant – ₹18 lakh per month in some cases. But in comparison to the magnitude of power generated, the penalties actually range between 0.12% – 3.28% of the energy cost. “There is no significant penalty being charged for non-compliance. The penalty is notional at best. Until a clear policy directive comes from the Centre, it’s difficult to get power producers to take compliance seriously,” said Karthik Ganesan, Fellow at Council on Energy Environment and Water (CEEW).

The David versus Goliath argument fits perfectly in this scenario as those who are ultimately suffering are citizens, especially those living around these coal plants. “There is a study by the Health Effects Institute, which estimated that in India, around 1.3 million deaths are likely to be recorded annually by 2050 because of the failure of thermal power plants to comply with pollution control norms,” said Vibhuti Garg, Energy Economist, IEEFA.

A comparative analysis by CEEW Urban Emissions between the cost of pollution control technology and social costs revealed that the capital cost of FGD installation translates to 30-72 paise/ KWh, depending on the capacity at which the plant is operating, plant load factor and life of the plant. The health and social costs drop from ₹8.58/KWh to 0.73 paise/KWh if the coal plants meet the standards.

Close to 20% of India’s installed coal capacity has already outlived their lives. With the Indian government making no secret of their desire for coal to feature prominently in India’s energy mix for the foreseeable future, one can only hope that this hunger is not satiated at the cost of public health and environmental considerations. Even the Supreme Court, which is often the last hurdle for industrial impudence regarding environmental regulations has been less than dependable when it comes to strict enforcement of norms, as is seen by the recent dilution of NOx emission norms for thermal power plants.

“The bottomline is this. How much do you actually pay for human life that has directly been lost? This is where we are losing the plot. Economics has its own place, but the health and fundamental rights of people has to also be given importance. No civilised society can allow such blatant disregard of the law,” reflects Dutta.

About The Author

You may also like

India’s EV revolution: Are e-rickshaws leading the charge or stalling it?

Is pine the real ‘villain’ in the Uttarakhand forest fire saga?

NCQG’s new challenge: Show us the money

India’s energy sector: Ten years of progress, but in fits and starts

9 years after launch, India’s solar skill training scheme yet to find its place in the sun