The roadmap’s focus is on mobilising private finance, which can potentially contribute more than half of the $1.3 trillion

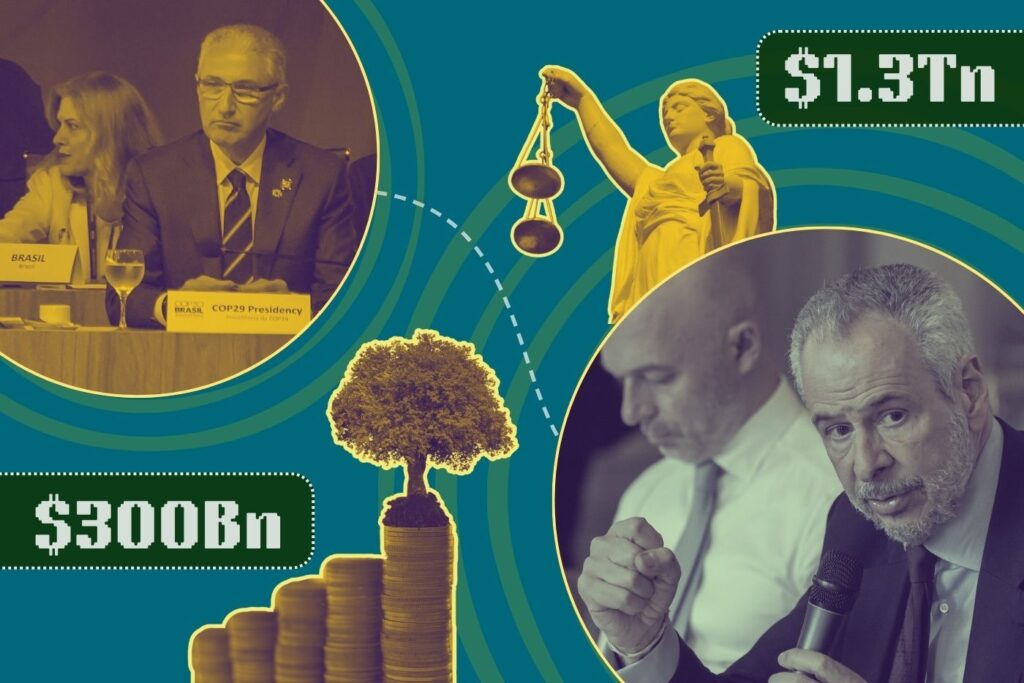

One of the more ambitious tenets set at COP29 in Baku last year was the ‘Baku to Belem Roadmap’ which aimed to mobilise $1.3 trillion in annual climate finance by 2035. While countries agreed to financing $300 billion annually, the question of realistically achieving $1.3 trillion remains. That is what the Roadmap, published late on Wednesday, attempts to do.

At its core, the Roadmap proposes a comprehensive and integrated 5R framework for “scaling up climate finance to developing countries for Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) and National Adaptation Plan (NAP) implementation and sustainable development supporting the achievement of 1.3 trillion”.

The 5Rs are:

1. Replenishing — Grants, Concessional Finance and Low-Cost Capital

2. Rebalancing — Fiscal Space and Debt Sustainability

3. Rechannelling — Transformative Private Finance and Affordable Cost of Capital

4. Revamping — Capacity and Coordination for Scaled Climate Portfolios

5. Reshaping — Systems and Structures for Equitable Capital Flows

The revamping aspect essentially calls for a structural change of the international financial architecture. The roadmap references “the Bridgetown Initiative on the Reform of the International Development and Climate Finance Architecture (2022); the Paris Pact for People and Planet (2023); and the African Climate Summit(2023).”

While this signals a positive outlook towards garnering more climate finance for developing countries, the absence of clarity on certain aspects can be a bit worrying.

“It is not well defined from where the financial support will come – private or public capital, whether it is loans, grants or equity, concessional debt. Defining the quality of climate finance is important,” says Labanya Jena, Director of Climate and Sustainability Initiative (CSI).

Undefined parameters

The roadmap lays out possible methods to achieve $1.3 trillion, referring to a report by the Independent High Level Expert Group (IHLEG). These include:

- Bilateral concessional finance from developed countries amounting to $80 billion

- Concessional and non-concessional multilateral finance from multilateral development banks and multilateral climate funds, amounting to $300 billion

- South-South cooperation, amounting to $40 billion

- Cross-border private finance (mobilized and direct), amounting to $650 billion

- New sources of low-cost finance including carbon markets, voluntary levies, Special Drawing Rights, debt swaps, and private philanthropy, amounting to $230 billion

However, this means that more than half of the $1.3 trillion needed will be reliant on private finance. This can be a potential problem, especially as the actual investment needed for climate resilience in developing countries is $3.2 trillion.

“Developing countries are raising a lot of debt, so raising more public debt may not be good for developing countries. Most of the money is going for mitigation. Is any form of capital coming only for adaptation? Development finance and adaptation finance are often interchanged, but a separate adaptation finance is needed,” says Jena.

Another thing is that adaptation finance is still taking the form of non-concessional loans, potentially increasing the debt burden for developing countries.

However, the roadmap is focused on addressing systemic bias in the financial architecture, and has proposed reviewing Basel III prudential rules. Furthermore, it has demanded credit rating agencies incorporate climate and nature benefits into their methodologies.

“The proposed roadmap pushes the right buttons. It highlights the importance of equity and fairness, and attempts to provide a coherent action framework to scale up finance in the short to medium term. The proposal for the developed world to communicate its ‘intended contributions and pathways’ towards achieving the at least USD 300 billion goal by 2035 is interesting, as it would help in measuring and monitoring the progress on finance delivery, and making finance a part of the ambition ratcheting cycle. It is imperative that ambition is not just about mitigation actions, it should also be about delivery of finance,” says Vaibhav Chaturvedi, senior fellow at the Council On Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW).

Biased methods

The absence of the principle of Common but Differentiated Responsibilities (CBDR) also raises eyebrows. This can absolve developed countries of their historic responsibility of emitting.

“Instead of demanding the grant-based public finance that developed countries owe as their ‘fair share’, it offers a reheated diet of market-based solutions, MDB reforms, loans and private capital. This is not the transformation we have been demanding but a dangerous evasion of wealthy countries’ responsibility. The report is silent on holding polluters accountable and glaringly omits the true financial gap for loss and damage. We need a roadmap that dismantles this unjust system and holds its architects accountable,” said Harjeet Singh, climate activist and founding director of Satat Sampada Climate Foundation.

The roadmap, said experts, focuses on ensuring a delivery system of the $1.3 trillion, but does not guarantee a methodological guarantee of ensuring that the pledged $300 billion is realised at COP30.

“Instead of arguing for $1.3 trillion, the Baku to Belem road map could have chosen to focus on using the agreed $300 billion effectively and efficiently by leveraging available concessional finance to crowd in and direct private commercial finance capital with focus on global stock of capital (and not annual flows), which is in excess of $200 trillion to long term low carbon transition, carbon dioxide removal and building climate resilience,” said Dhurba Puryakayastha, a climate finance and sustainable development expert.

However, this roadmap will not be up for negotiation. Being a presidency document, it will serve as a guideline for countries during negotiations, rather than adopted in its entirety. The roadmap also emphasises improving the process, and not on securing immediate funding for developing countries.

As of now, developed countries are supposed to publish updated finance plans by the end of 2026 under Article 9.5 of the Paris Agreement, which would be taken up by the UN’s Standing Committee on Finance by October 2027.

What this roadmap achieves is accepting that $300 billion is the minimum limit needed as climate finance by 2035, which India had reiterated at COP29 last year. The document asks the UN climate funds—the Green Climate Fund, the Global Environment Facility, the Adaptation Fund, the LDCF/SCCF and the Loss & Damage Fund—to pay out three times as much each year by 2030 as they did in 2022. That helps put focus on actual money disbursed, not headline pledges.

About The Author

You may also like

Rising Global Energy Demand Fuel Security Threats: WEO Report

Finance, tensions and protests: Day 2 at COP30

COP30 kicks off with eyes on big developing countries

World Off-Track on Climate Goals as Temperatures are Predicted to Rise: Report

Brazilian President Calls For Fossil Fuel Phase Out, launches Biofuel Push at COP30