As private capital powers India’s renewable energy growth, can the same momentum drive investments towards other emerging green technologies?

India’s renewable energy sector has thrived—raising $80 billion in private investment. But can this success be replicated across other green industries?

“Money will be available for any project in India which makes financial sense, where the investor can make around 10% returns. But projects which don’t have cashflow, that’s where climate finance is required,” says Neshwin Rodrigues, a senior analyst at the London-based energy think tank Ember.

By “money”, he’s referring to private finance, which has allowed the renewable energy sector to flourish in India. An earlier report by Carboncopy delved into how India’s renewable energy market has matured.

From an economically self-reliant perspective, India’s renewable story is important, especially at the backdrop of the disappointing COP29 climate finance negotiations last year.

Collectively, 196 countries – 44 least developed and 152 developing – demanded $1.3 trillion, but were only pledged $300 billion, which include no public funds, by 23 developed nations over the next ten years.

India’s clean transition needs $2.5 trillion by 2030. Despite this massive requirement, the world’s fastest growing major economy is understandably not high on the priority list of climate donors.

Yet, while India does not expect large grants to fund its clean transition, it does need investments and concessional loans for its industry. The country’s renewable energy sector stands as an example of the country’s capacity to offer returns to investors. The sector attracted investments worth ₹7 trillion ($80 billion) between 2013-2014 and 2022-23, Pralhad Joshi, Union minister for new and renewable energy told the Parliament earlier this month. About a quarter of India’s clean transition needs, it far exceeds the investments attracted by any other clean sector in India.

While the relative success of the green energy market in India brings with it investment opportunities, the same cannot be said for other markets of clean technologies like battery storage and green hydrogen.

These sectors will have to stand on their own economic merit. “The only thing that grid scale renewables – which stores excess electricity – can do is provide confidence by ensuring that the majority of companies grow their clean energy portfolios and are able to transition. There has to be policy support and financial incentives provided,” says Shantanu Srivastava, the sustainable finance and climate risk lead at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA).

Although critical, green energy is only one component of the many adaptation and mitigation measures that developing countries need to scale up quickly and efficiently.

If historical emitters won’t pay for the warming they’ve caused, can India rely on private sector investments to fund its own transition?

Climate finance comes with limits

“Climate finance is additional. But if funding does not come, what do you do?” says an analyst at a reputed securities firm, on condition of anonymity, as they are not authorised to speak with the media.

“You have to meet your energy demands. So growing renewable energy turns out to be the most economical thing to do. As time passes, renewables become cheaper and more scalable. It will take off, despite a lack of adequate climate finance,” they say.

Srivastava shares this optimistic view. According to him, as renewables are commercially viable and can stand on their own, investment will come through private finance, whether through ESG or sovereign funds or domestic banks.

But unlike mitigation, which has well-defined parameters for investors, adaptation finance has so far remained comparatively vague and difficult to fund for various reasons.

Mitigation projects, like renewable energy, attract investment, while adaptation projects—such as sustainable housing, resilient agriculture, and climate-proof infrastructure—remain underfunded.

“Given its scale, India has been attracting a significant amount of funding for mitigation from multilateral and bilateral sources, but not for adaptation. Adaptation funding primarily comes from local financial resources, with only a small portion provided by multilateral and philanthropic organisations,” says Vaibhav Pratap Singh, executive director of the Climate and Sustainability Initiative (CSI).

Till 2022, $116 billion was received by developing nations as climate finance, of which mitigation finance accounted for 60%, found a report.

Need for taxonomy

The recently tabled Economic Survey recognised India to be the 7th most vulnerable country to climate change, with 93% of days in 2024 facing extreme weather events like heat, heavy rainfall, flooding, landslides.

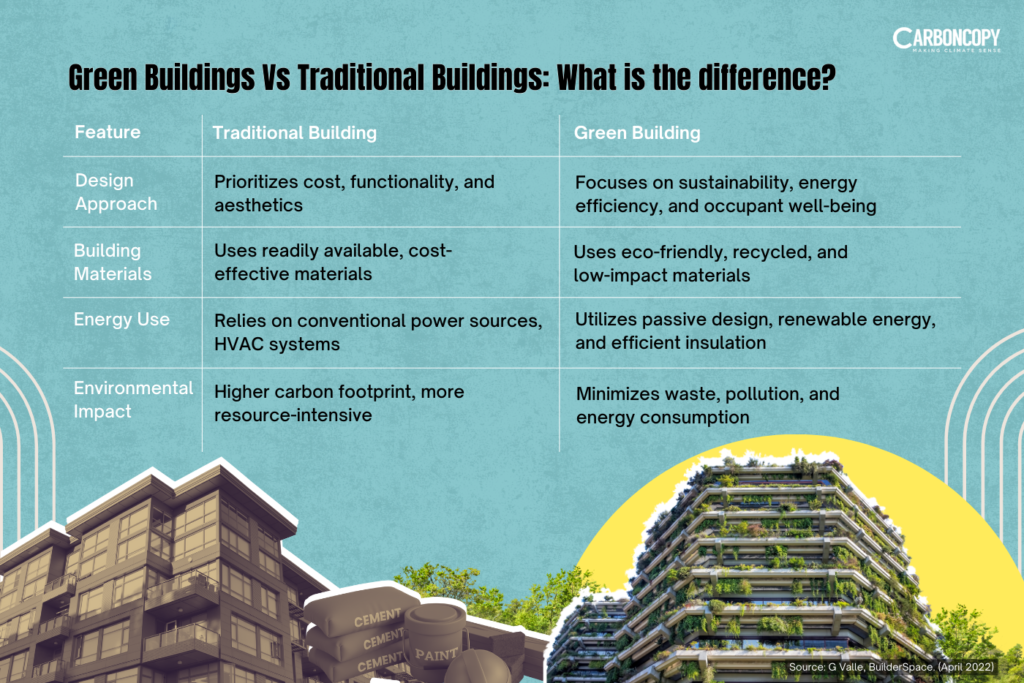

India needs to adapt, and quickly. Among the pressing priorities are providing resilient and sustainable housing. But the primary paradigm is still concrete, steel and glass — materials with high rates of embedded emissions.

Green buildings being cheaper to build and selling at premium rates thanks to the “sustainable” tag. There’s an obvious market sense, but it is still not taking off majorly. Why?

A lack of definition as to what constitutes “green buildings” or “sustainable agriculture” is a major hurdle. Green taxonomy – which classifies economic activities and assets as sustainable, and thereby aids in directing investment – is needed. Having clarity on what constitutes mitigation and adaptation can make it easier for finance to be funneled into sustainable development. For example, the EU Taxonomy is helping chart a clear path for EU states to achieve net zero by 2050, by being one of the fundamental pillars of the EU’s sustainable finance framework.

“India is largely a bank-financed economy, establishing a taxonomy that categorises sectors such as sustainable agriculture, housing, and industries etc. can enhance the flow of finance to these areas. This approach will also improve funding for adaptation-related aspects within these sectors,” says Singh.

More importantly, financing instruments for the existing methods of construction remain dominant. There’s no pressing need to bring about change. In other words, if it ain’t broken, why fix it?

Rethinking green construction

“A completely green building is still a theoretical concept. The moment we get into construction or start building, there’s a lot of carbon footprint accumulating through labour, machinery, vehicles,” says Nachiketa Mohanta, an architect who heads the firm Studio of Illusion based out of Puducherry, Tamil Nadu.

“What works is that when you build for sustainable use, you don’t need to break the structure every 20-30 years. As architects, we design buildings for a longer term. Build fewer buildings, which reduces carbon footprint,” says the architect, who’s been working for 12 years, making mud and lime based homes.

Energy efficiency through natural lighting, cooling and heating, can lend sustainable elements, offers CSI’s Singh. Government housing programs for the underprivileged such as the PM Awas Yojana – Gramin (PMAY-G) and Awas Yojana Urban (PMAY-U) incorporate some green design principles, but broader policy support is needed.

Under PMAY-G, there’s a target of building 3.32 crore houses. As of November 2024, 3.21 crore houses have been sanctioned, and 2.67 crore houses have been completed. Under PMAY-U, the target is 1.18 crore houses, out of which 1.14 crore houses have been grounded for construction, while 83.67 lakh houses have been completed, as of June 2024.

One way of making housing green is by decarbonising the cement and steel industries, which spills over to other industries, and brings its own set of challenges.

Crucially, alternative construction faces a major barrier—nothing can substantially replace coal energy to process raw material into construction material. Using green hydrogen would make it very expensive.

Another strategy is using locally available materials, which reduces costs and carbon emissions as transportation and labour becomes lesser, says Mohanta. “Soil, being a thermal element, keeps buildings cool during summer, and warm during winter. Soil buildings last longer as it gets stronger over time, but concrete based buildings don’t last as long,” he says.

But natural materials have limitations – ideally, they cannot be used for buildings which are higher than four stories. For high-rise buildings, especially in urban areas, steel and glass structures are necessary. Also, since soil and mud are not readily available in cities, transporting them shoots up the cost and carbon emissions, says Mohanta.

Systemic change required

For green buildings to become the main paradigm, a big change is needed. Big construction companies like DLF and L&T have to primarily build alternative houses. Infrastructure needs to scale up, and lobbying by cement and steel industries will have to be dealt with.

Most importantly, there aren’t enough people in the construction industry who can build green structures.

“There is not enough training for mud-based buildings. Large-scale training schemes for architects, and workers are absent. While small organisations are doing courses in Auroville and Bangalore, it is not economically accessible to everyone, especially local contractors. Normal masons cannot avail it. It is still a very niche market,” says Mohanta.

In his experience, he finds skilled labour for alternative construction in towns like Pondicherry and Auroville, but the number decreases in cities like Chennai and Bangalore.

This is where the government needs to step in with training schemes and supporting alternative housing through its own housing projects, hospitals, schools, public buildings, says Mohanta. This is where public finance can play a role by allocating specific funds for such projects, which is readily not available in the market. Subsidising the construction of green real estate, even for a few initial years, can go a long way in incentivising the private sector to mobilise finance, as evidenced in the electric vehicle ecosystem.

“Public buildings are generally funded by the government, and that is where initiatives can be introduced. That would be the best way to reach the maximum number of people,” he says.

This way, blended finance – wherein both public and private funds come together in certain ratios to support sustainable projects and development – can be unlocked for India’s adaptation aspirations.

Unlocking finance for adaptation

Securing finance for adaptation work is challenging as commercial finance firms are looking for returns.

“Adaptation has minimal business cases, and can happen on a small scale in specific regions. For example, building storm shelters in Odisha will not generate revenue, so private finance won’t be available for it. The government has to bear the cost,” says CSI’s Singh.

According to Ashish Fernandes of Climate Risk Horizons, there is little option at the moment except development finance – low-cost loans – through multilateral development banks (MDBs), bilateral deals or philanthropy.

“We can’t expect much of low cost finance coming in. In the sectors where we have shown there is viable finance, like renewable energy, there is probability to raise funds,” he says.

Then again, according to Fernandes, now that the renewable energy sector is established, the focus should be on more derisking mechanisms – wherein strategies are implemented to reduce the amount of risk involved in financing and running the project – for decarbonisation technologies like green hydrogen, electric arc furnaces for steel industry etc.

“We need concessional finance in those sectors. This could involve initial investments by MDBs and large philanthropic institutions. This would open gates for more commercial lenders, as the risk is reduced. In other words, leveraging a smaller pot of loans for getting a bigger pot,” he says.

The answer for a net zero future might be found looking inwards, especially if developing nations cannot rely on climate finance from the developed world.

If we have to turn to private finance, then India’s renewable energy market growth carries a lesson in self-sustainability for the Global South and for other emerging markets. If the economics makes sense, money will follow.