India is the world’s third largest emitter of greenhouse gases (GHGs), after China and the US.

India is also very vulnerable to climate change, notably due to the melting of the Himalayan glaciers and changes to the monsoon.

The country has pledged a 33-35% reduction in the “emissions intensity” of its economy by 2030, compared to 2005 levels.

It is holding a general election this year throughout April and May, with polls projecting a minority win for current prime minister, Narendra Modi.

Politics

India has the world’s second largest population, at 1.3 billion. Its economy ranks sixthglobally in terms of gross domestic product (GDP), just after the UK, and is the world’s fastest growing major economy. India’s population is expected to become the world’s largest by 2025, overtaking China and peaking at 1.7 billion in 2060.

Modi first won office in May 2014. His party, the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), was the first in 30 years to win an outright parliamentary majority. The BJP won 31% of the vote and 52% of seats; the centre-left Indian National Congress (INC) came second with 19% of votes and 8% of seats.

Modi has portrayed India as a responsible participant in international climate politics. In 2018, he told world leaders that climate change is the “greatest threat to the survival and human civilisation as we know it”.

India will begin its election on 11 April 2019, with the final ballot cast on 19 May and the results expected on 23 May. Around 900 million people are eligible to vote. The election result is hugely complex to predict. However, opinion polls in January-February 2019 generally show an expected minority or slight majority win for Modi’s party. The INC, led by Rahul Gandhi – son and grandson of two former prime ministers – is expected to come second.

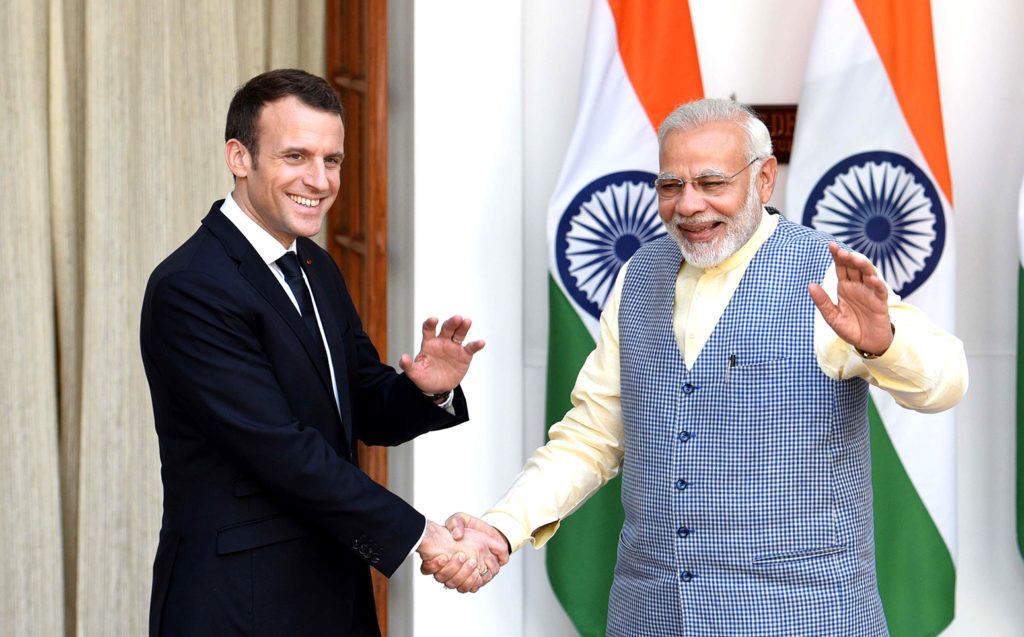

Prime minister Narendra Modi with French president Emmanuel Macron at Hyderabad House, New Delhi, on 10 March 2018. Credit: Newscom / Alamy Stock Photo.

India’s constitution, adopted in 1949, says the state shall “endeavour to protect and improve the environment” and “safeguard [India’s] forests and wildlife”. Its 2006 National Environment Policy aimed to integrate environmental protection into the development process.

In 2002, India hosted the eighth formal meeting of the UNFCCC (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change) in New Delhi. This meeting adopted the Delhi Ministerial Declaration, which called for developed countries to transfer the technology needed to cut emissions and adapt to climate change to developing countries. This remains a key priority for India at climate talks. The issue of how to fairly share up ambition, known as “equity”, also continues to be a strong concern for India.

Three-quarters of Indians are very concerned about global warming, according to a 2015 poll from the Pew Research Centre, the highest share of all the Asian countries surveyed. In another 2017 survey, 47% called climate change a “major threat” to their country, second only the threat of ISIS.

Around 13% of India’s population does not yet have access to electricity, while more than half still relies on traditional biomass (dung, wood, etc) for cooking. Modi has repeatedly promised to ensure all Indian homes are connected with electricity, most recently for the end of March 2019, although the quality of power access remains poorfor many.

Paris pledge

India is part of four negotiating blocs at international climate talks. These are BASIC, a coalition of the four major emerging economies with Brazil, South Africa and China; the like-minded developing countries (LMDC); the G77 + China; and the Coalition for Rainforest Nations (CfRN).

Its GHG emissions in 2015 stood at 3,571m tonnes of CO2 equivalent (MtCO2e), according to data compiled by the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK). Emissions increased over three-fold since 1970.

India’s per capita emissions stood at 2.7tCO2e in 2015, around a seventh of the US figure and less than half the world average of 7.0tCO2e. (See “note on infographic” at the end of this article for details on use of 2015 data).

India ratified the Paris Agreement on 2 October 2016, almost exactly a year after it submitted its climate pledge, or “nationally determined contribution” (NDC), for the Paris climate talks.

The pledge is for a 33-35% reduction in emissions associated with each unit of economic output (“emissions intensity”) by 2030, compared to 2005 levels. Carbon Brief analysis at the time found India’s emissions could increase 90% between 2014 and 2030, even if the pledge is met.

![]()

India also aims for 40% of its installed electricity capacity to be renewable or nuclear by 2030.

It further outlines plans to increase tree cover to create an additional cumulative carbon sink of 2,500-3,000MtCO2e by 2030 – roughly on a par with its total emissions across one year.

The pledge says India’s goals represent the “utmost ambitious action in the current state of development” and criticises the “tepid and inadequate” response of developed countries to global warming. “India, even though not a part of the problem, has been an active and constructive participant in the search for solutions,” it says.

India is clear that implementation of its pledge will depend heavily on climate finance, technology transfer and capacity building support from developed countries. In total, it estimates it will need at least $2.5tn up to 2030, from both domestic and international funds.

India’s NDC is consistent with the 2C goal of the Paris Agreement, but not the 1.5C limit, according to Climate Action Tracker (CAT), an independent analysis of climate pledges produced by three research organisations. However, the top end of India’s policy range is 1.5C compatible, says CAT.

India is now on track to overachieve its Paris targets, after adopting its final National Electricity Plan (NEP) in 2018, says CAT.

The country could achieve its 40% non-fossil power capacity target more than a decade early, through the use of hydroelectricity and nuclear power, adds CAT. India’s emissions intensity in 2030 will be around 50% below 2005 levels, CAT projects, far ahead of the 33-35% target.

A “barefoot” solar engineer from Tinginaput, India, passes on her skills to other villagers teaching them how to make a solar lamp. Credit: Abbie Trayler-Smith / Panos Pictures / Department for International Development.

A less rosy assessment comes from Climate Transparency, a research and NGO partnership which aims to spark ambitious climate action. It says India’s NDC is compatible with limiting temperature rise to below 2C, but that current (2018) policies fall short of this.

The Indian government is considering long-term growth strategies for 2030-2045, which would “decouple” carbon emissions from economic growth, says CAT. India has indicated it may be willing to increase its climate pledge in 2020. However, it has notyet translated the Paris Agreement goals into domestic law.

India published its National Action Plan on Climate Change (NAPCC) in 2008, split into eight missions on diverse aspects of climate mitigation and adaptation policy. Each of the eight missions is discussed in the relevant sections, below.

India’s states are also required to produce state climate action plans. Some of these include emissions reduction commitments, e-mobility policies or solar and wind capacity quotas.

Coal

India is the world’s second largest coal consumer after China, having overtaken the US in 2015.

Moreover, Chinese coal use has plateaued, meaning India could largely determine the global trajectory for the fuel. Many analysts expect rapid growth in India to drive increases in global demand over the next few years – though this is expected to remain below a peak in 2014.

Coal has fuelled the rapid growth in Indian electricity use and its coal fleet has more than tripled in size since 2000. In 2017, coal generated 76% of India’s electricity, as shown in the chart below (black area).

Electricity generation in India by fuel, 1985-2017 (Terawatt hours). Source: BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2018. Chart by Carbon Brief using Highcharts.

As of January 2019, India has 221 gigawatts (GW) of operating coal plants. This is the world’s third largest fleet, with 11% of global capacity, according to the Global Coal Plant Tracker. Another 36GW is being built and a further 58GW is at earlier stages of development. This pipeline of new plants is rapidly drying up, however, having shrunkby more than a quarter since last year and more than five-fold since 2014.

The government currently projects there will be 238GW of coal capacity in 2027. An earlier draft NEP had no plans for coal expansion before 2022, bar the 50GW already being built. However, the final version included more than 90GW of planned coal-fired capacity, which some argue now risks becoming “stranded assets”. Abandoning plans to build new coal-fired plants could make India’s policies 1.5C compatible, says CAT.

There is ongoing debate about the extent to which new coal will actually get built in India, as well as how often existing plants will run, given falling costs for renewables and lower-than-expected growth in electricity demand. Forecasts for Indian coal demand growth have been repeatedly revised down and one recent analysis said a large proportion of the pipeline of new coal plants could be cancelled.

There is concern in India over the health impact of coal plants. One in every eight deaths in India is due to air pollution, according to a recent report in the Lancet Planetary Health, while India is home to half of the world’s 20 most polluted cities. The falling cost of solar power and batteries is also having a significant impact on the sector.

Coal being sorted by size and quality, Meghalaya, India. Credit: National Geographic Image Collection / Alamy Stock Photo.

In 2015, India set new emissions standards for air pollution from coal plants for compliance in 2017, with looser standards for older plants. However, the standards were not complied with and India’s supreme court has now extended the deadline for meeting them to 2022.

India is the second largest coal producer and importer, after China. Coal India, the national coal mining company and largest coal producer in the world, accounts for around 84% of domestic output. India has proven coal reserves of around 98bn tonnes, or 9.5% of the world total, again second only to China.

The government hopes to end imports, which come from Indonesia, South Africa and Australia. It has a target for Coal India to reach 1,000Mt of production by 2019-20, up from 650Mt in 2018-19, although timeline may be relaxed.

India says it needs to use coal to secure “reliable, adequate and affordable supply of electricity”, but that it has also taken steps to improve the efficiency of its coal plants.

In 2010, it introduced a coal “cess” (tax). This collected $12bn from 2010-2018. It is expected to bring in $1bn more in 2019 and 2020. However, subsidies for coal also remain high, at $2.3bn in 2016, largely as tax breaks to the mining sector.

Coal makes up almost half of local revenues in some states in India, meaning a move away from it would require policies to ensure a “just transition” for coal workers. There is reportedly little discussion on this in India. However, a major vocational programmelaunched in 2015, to boost youth employment, has renewables as a target sector.

Interactive map of historical and planned coal power plants in India

Low-carbon energy

India is notable for its rapid expansion of renewables in recent years. In 2017, renewable investment and new capacity topped fossil fuels for first time. However, only15.5% of India’s electricity came from renewables in 2017, including 9.1% from large hydro.

Rapidly falling solar PV prices mean coal-based power is falling out of favour with electricity distributors. However, as the penetration of renewables in the grid increases, new policies, such as smart grids, will be needed to adapt to the variable supply.

Gujarat Solar Park, in Gujarat, India, in 2013. It now has an installed capacity of 1637 MW. Credit: Ashley Cooper / Alamy Stock Photo.

Overall, subsidies to renewables in India increased from $431m in the 2014 financial year to $1.4bn in 2016, the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) says. Support to coal, oil and gas was still around six times this in 2016, IISD notes.

India used its Electricity Act back in 2003 to begin promoting renewable electricity. In 2015, it set a goal to install 175GW of renewable energy capacity by 2022, consisting of 100GW solar, 60GW onshore wind,10GW bioenergy and 5GW small hydro. This could replace roughly 70GW of coal, according to a Carbon Brief guest post last year. India’s total current capacity, including fossil fuel and low-carbon plants, is around 350GW.

In June 2018, India’s power minister Raj Kumar Singh said he expects India to have built or commissioned all 175GW by March 2020. Renewables reached 72GW by September 2018.

Singh also said in 2018 that he country now hopes to reach 225GW renewables by 2022. However, this target may be due to the government giving large hydropower the status of being “renewable”. India’s most recent NEP projects that 275GW renewables will be installed by 2027.

Its 2016 revised Tariff Policy obliges power distributors and some large electricity users to buy a proportion of their energy from renewable sources. It also waives inter-state transmission charges for solar and wind energy.

India launched its “National Solar Mission” in 2010, one of the eight NAPCC missions. Its original target was 20GW solar by 2022, but this was increased in 2015 to 100GW. Rooftop solar is supposed to account for 40% of this.

India also plans 2GW of off-grid solar by 2022, including 20m solar lights in rural areas.

By August 2018, 23GW of solar had been installed or commissioned, according to India’s recently submitted biennial report to the UNFCCC. It is building many of the world’s biggest solar parks.

However, short-term financial uncertainty due to changing taxes on solar and tariff renegotiations could mean India misses the 100GW target, says consultancy firm Wood Mackenzie.

India is the fourth largest wind power globally, after China, the US and Germany. Around 34GW of onshore wind had been installed by mid-2018, triple the level seen a decade ago. India is using auctions to reach its 2022 wind target.

The price of solar has fallen by almost two-thirds since 2014, while the price of onshore wind has halved, India’s biennial report says.

India also aims to install 5GW of offshore wind by 2022 and 30GW by 2030. None has yet been installed, however.

India’s renewable energy potential is around 1,100GW for commercially exploitable sources, the biennial report says. This includes 300GW wind and 750GW solar power. The country could integrate 390GW of low-cost wind and solar generation into its grid by 2030, according to the Climate Policy Initiative (CPI).

India’s climate pledge notes that around 70% of its population depends on traditional biomass energy, which is inefficient and causes high levels of indoor air pollution. India is promoting the use of biomass to generate electricity instead, which it says is cleaner and more efficient. India is targeting 10GW of such bioenergy by 2022 and had already reached 9GW in 2018.

India has around 4.5GW of small hydro (plants below 25MW), against a 5GW target for 2022. Including large hydro, capacity sat at 45GW in 2018, up from 30GW in 2005. India’s climate pledge says it will “aggressively pursue development of the country’s vast hydro potential”.

India’s government views nuclear power as a “safe, environmentally benign and economically viable” source of electricity, according to its 2015 climate pledge. It currently has 6.8GW of nuclear capacity and targets a nine-fold increase to 63GW by 2032. However, there is ongoing debate in the country on the pros and cons of nuclear energy.

India also has one of the world’s largest reserves of thorium – seen as a safer alternative to existing nuclear fuels – and has a long-term interest in experimental thorium reactors. However, substantial generation is unlikely until at least the 2050s, if at all.

Energy efficiency

India has long prided itself on its energy efficiency and emissions intensityachievements.

Its 2001 Energy Conservation Act established the Bureau of Energy Efficiency, which was tasked with reducing the energy intensity of the economy.

India says it is on track to meet its voluntary goal of cutting emissions intensity 20-25% by 2020, compared to 2005 levels. However, it also notes how little energy is used by the average Indian citizen, compared to those in other countries.

In 2010, India launched its National Mission for Enhanced Energy Efficiency (NMEEE), another of the eight NAPCC missions. This targets an eventual 20GW in avoided electricity generating capacity and 23m tonnes of fuel savings per year.

Bricks lined up to dry at a brick manufacturing facility in Amritsar, Punjab, India. Credit: GURPREET SINGH / Alamy Stock Photo.

The market-based Perform, Achieve and Trade (PAT) scheme is its main initiative. This limits the consumption of energy-intensive industries, including thermal power plants, iron and steel, and cement. Overachievers can sell their energy saving certificates to those that have fallen short.

Its first cycle led to savings of 31MtCO2e between 2012 and 2015, the government says, which is around 1% of India’s current annual emissions. The scheme has been extendedseveral times to cover more and more sectors.

Other NMEEE schemes include support for more efficient appliances, such as ceiling fans, encouragement for financiers to engage in energy efficiency and the use of financial instruments, such as partial risk guarantees and venture capital, to support energy efficiency.

India also has a national smart grid mission, a rating system to evaluate the energy performance of buildings and another for small industries to support more environmentally friendly manufacturing.

It recently released a new action plan to cut cooling energy requirements – a significantdriver of electricity demand growth – 25-40% by 2038. The plan also aims to cut refrigerant demand by 25-30% by the same year.

The government aims to replace India’s 14m conventional street lights with LEDs by 2019. It is also subsidising the rollout of LEDs in homes, with 312m distributed so far.

Transport

India currently has the world’s fifth largest car sales. These are expected to grow with rising incomes and rapid urbanisation, with strong implications for global oil demand.

The government promotes the uptake of electric vehicles (EVs), although so far India has only 260,000 – including two-wheelers and hybrids – and, overall, only 0.6% of sales are EVs. The rollout of charging stations remains low.

It also has around 1.5m electric rickshaws, although these are typically used only for short journeys.

Electric rickshaw carrying villagers at Mangalbari bustee, Chalsa in Jalpaiguri district of West Bengal, India. Credit: Biswarup Ganguly / Alamy Stock Photo.

In 2011, India set up its National Mission for Electric Mobility, which aimed to promote electric vehicle (EV) and hybrid manufacturing. In 2017, then-power minister Piyush Goyal said petrol and diesel car sales should end by 2030. But the government has since rowed back on this aim, now targeting a 30% share of sales for EVs by 2030. It also aimsfor all new urban buses to be fully electric by 2030.

In 2015, India launched its FAME scheme to subsidise electric and hybrid cars, mopeds, rickshaws and buses. This was recently extended with a fresh $1.4bn over three years. Of this, $1.2bn is earmarked for subsidies and $140m for charging infrastructure. Several individual states have also rolled out policy initiatives to support EVs.

India finalised its first passenger vehicle fuel efficiency standards in 2014. These entered force in 2017 and will be tightened in 2022, though even then they will be less stringent than current standards in the EU.

Its 2009 national biofuels policy had an “aspirational” target to blend 20% biofuels into the diesel and petrol mix by 2017. However, India has fallen well short of these targets, so far reaching only around 2% bioethanol and 0.1% biodiesel blend in 2018. It updatedits biofuels policy in 2018, proposing a 20% blend of bioethanol and 5% of biodiesel by 2030.

India’s railway system is the fourth-largest in the world in terms of rail track length. It is second only to China in terms of rail passenger activity, with this set to grow more than any other country, tripling by 2050.

Around half of India’s conventional rail tracks are electrified, although its first high-speed line is still under construction. A third of India’s land freight is carried by rail, a high proportion by global standards, with coal by far the main commodity.

India plans to increase the share of railways in total land transport from 36% to 45%, its climate pledge says, including through development of dedicated freight corridors.

Aviation only represented 1% of India’s emissions in 2014, well below the world average, but its rapid expansion means this has already likely increased. India has the world’s fastest growing domestic aviation market, with a 19% rise seen last year alone. It aims to construct around 100 new airports in the next 10-15 years and is set to become the world’s third largest market by 2020. Passenger numbers for domestic and international flights have already doubled since 2010 and could triple to 520 million by 2037.

India is a signatory to Corsia, the UN aviation emission offset scheme, although it has not signed up for the voluntary pilot phase set to begin in 2021.

Its climate pledge outlines plans to promote coastal shipping and inland water transport, due to their fuel efficiency and cost effectiveness.

Oil and gas

India relies on large amounts of oil, which made up 29% of total energy consumption in 2017. Its oil demand is rising fast and could more than double by 2040.This means it could soon overtake China as the top driver of global oil demand growth. However, its own oil production is falling.

The government has provided large consumption subsidies to both oil and gas. Between 2014 and 2016, subsidies fell by almost 75% to $6.8bn, due to reforms and falling oil prices. Further reforms are ongoing.

India has highlighted its use of subsidy cuts and petrol and diesel tax rises to address climate concerns. For example, a “Give it Up” campaign launched by the Indian government encourages more affluent citizens to voluntarily give up their subsidy for LPG cooking gas.

However, price changes in fuels such as kerosene – widely used for lighting and cooking in India – could have large impacts on those without access to electricity.

Diesel consumption is expected to rise, supported by large government spending on road-building,

Gas has never played a prominent role in India’s energy mix, making up only 6% of energy consumption in 2017. India currently imports around half its gas, largely from Qatar, the US, Australia and Russia.

However, gas consumption is rising in India, although its higher price means it struggles to compete with coal and fuel oil. The government aims to more than double the share of gas in the energy mix to 15% by 2022, citing the environmental benefits of adopting it as a “cleaner fuel”. Domestic production is low and India will likely continue to be highly reliant on imports, despite the “substantial potential” of its domestic gas and oil reserves.

A parliamentary panel recently concluded that more than half of the country’s 25GW of gas power plants had been “stranded” by a lack of domestic gas and the high price of imports. India has reportedly considered “emergency stockpiles” of gas, similar to strategic oil reserves.

Agriculture and forests

Agriculture is responsible for around 16% of India’s GHG emissions. Of this, 74% is due to methane produced from livestock – largely cows and buffalo – and rice cultivation. The remaining 26% comes from nitrous oxide emitted from fertilisers.

Nearly two-thirds of the population rely on farming as their source of livelihood. India has 15% of the global cattle population, with around 300m cows and buffalo in 2014. It produces 19% of the world’s milk.

India will also need to substantially increase food grain production to feed its growing population, its climate pledge says. But droughts and floods are “frequent” and the sector is “already facing a high degree of climate variability,” it adds.

India’s National Mission for Sustainable Agriculture (NMSA), another of its eight NAPCC missions, aims to tackle agricultural emissions and enhance food security.

The country’s many initiatives include promotion of lower methane emission rice production, crop diversification away from rice, chemical-free farming and soil healthpilot projects. A policy introduced in 2015 made neem coating of urea compulsory to reduce nitrous oxide emissions.

Irrigation using highly inefficient water pumps accounts for around 70% of the energy consumption of agriculture. India has installed 200,000 solar water pumps – about 1% of the country’s total 21m, with another 2.5m planned.

India’s forest cover has increased in recent years, its climate pledge says, becoming a net CO2 sink. A recent study found India accounted for 7% of the global net increase in leaf area from 2000-2017.

Its long-term goal is to bring 33% of its area under forest cover – some 109m hectares – up from 24% in 2013 (79m hectares).

A herd of Indian cows near Mount Abu hill in Rajasthan, India. Credit: Kailash Kumar / Alamy Stock Photo.

Another goal is to absorb 2,500-3,000MtCO2 by 2030 through additional forest and tree cover. According to CAT, over half of this target could be achieved by the Green India Mission, launched in 2014, which aims to expand tree cover by 5m hectares and increase the quality of another 5m hectares of existing cover in 10 years. India’s government also offers incentives for state action to increase forest cover by linking itto funding allocations.

However, some argue India’s data exaggerates its true forest cover and masks ongoing deforestation.

Impacts and adaptation

India dedicates a large part of its 2015 climate pledge to outlining current and expected adverse impacts on the country. It says:

“Few countries in the world are as vulnerable to the effects of climate change as India is with its vast population that is dependent on the growth of its agrarian economy, its expansive coastal areas and the Himalayan region and islands.”

In its biennial report, it similarly points out it is already highly vulnerable to natural disasters, such as floods, droughts and cyclones, with these risks compounded by changing demographics and socio-economic conditions.

India’s annual mean temperature has already risen by around 1.0C since 1850.

The country could see $1.2tn of “lost GDP” in total, plus lower living standards for nearly half its population by 2050, compared to a scenario with no climate change, according to a 2018 World Bank study. The losses would be due to rising temperatures and changing monsoon rainfall patterns, the study says..

The Indus river flowing through the Ladakh range of the Himalayas. Credit: Parvesh Jain / Alamy Stock Photo.

The Himalaya mountains, which form the most important concentration of snow outside the poles, are one particularly vulnerable part of India and the wider South Asia region. The glaciers are a critical water source for 250 million people who live in the region. A further 1.65 billion people in India and seven other countries rely on the major rivers that flow from it.

A major report released earlier this year found rising temperatures will melt at least a third of the region’s glaciers by 2100, even if average global temperature rises are limited to 1.5C.

India is also vulnerable to increases in vector-borne diseases, such as malaria and dengue, which could both see increases due to climate change.

Heatwaves are also expected to be an issue, with 600 million people currently in locations that could become moderate or severe hotspots by 2050, according to the World Bank. India’s largely agricultural workforce was already significantly impacted by extreme heat in 2017, according to the Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change.

India could see significant sea level rise, affecting the river water systems that hundreds of millions rely on for food. Its 1,238 islands are also at risk.

The country’s disaster management act came into force in 2005. This made no explicit mention of climate change, but aimed to move from a “response and relief” approach to “prevention-mitigation and preparedness”. In 2016, India launched a disaster management plan, which integrates the principles of the Paris Agreement alongside other global disaster risk reduction frameworks.

India has dedicated one of its eight NAPCC missions to protecting the Himalayan ecosystem. Another two missions focus on water and research and development.

Its most recent National Communication report under the UNFCCC – which includes an assessment of vulnerability and adaptation – was submitted back in 2012.

Climate finance

India has long put a key emphasis on the need for climate finance and technology transfer from developed to developing countries. Its climate pledge notes:

“[O]ur efforts to avoid emissions during our development process are also tied to the availability and level of international financing and technology transfer since India still faces complex developmental challenges.”

India’s says it will cost at least $2.5tn to implement its climate pledge, around 71% of the combined required spending for all developing country pledges.

India received by far the highest level of single-country funding ($725m) approved by multilateral climate funds in absolute terms from 2013 to 2016, according to Carbon Brief analysis. The majority was from the Clean Technology Fund (CTF) for renewable projects. However, per-capita funding was relatively low, at just $0.56 per person..

On a wider level, India received on average $2.6bn per year in 2015 and 2016 in climate-related development finance, according to Carbon Brief analysis of Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) data.

India also has several domestic climate finance initiatives. As well as money spent through its eight national missions, its coal cess has so far collected $12bn, with proceeds used to finance clean energy, albeit not exclusively. Several adaptationprogrammes have also been allocated government funding.

Note on infographics

Data for energy consumption comes from BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2018. Greenhouse gas emissions up to 2016 come from combining emissions data compiled by the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK).

The graph showing emissions by sector comes from combining two datasets. Values for methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O) and fluorinated gases cover all sectors, including LULUCF, and come from the PIK primap database v2.0. Values for GHG emissions from LULUCF also come from the PIK primap database, however these are only available to 2015, and from the earlier v1.2 of the database.

This combined PIK primap database v1.2 and 2.0 data for GHG emissions in 2015 also shows India has the world’s third largest greenhouse gas emissions (inc LULUCF). India’s pledge to reduce the “emissions intensity” of its economy 33-35% by 2030, compared to 2005 levels, comes from its NDC submitted to the UN in 2015. Its aim for 40% of installed electricity capacity to be renewable or nuclear by 2030 also comes fro this pledge.

Per capita emissions in 2015 come from combining above 2015 figure for GHG emissions and India’s population in 2015 from the World Bank.

The remaining values come from the EDGAR CO2 emissions database, downloaded from the website OpenClimateData. The EDGAR categories described in full are as follows: Buildings (non-industrial stationary combustion: includes residential and commercial combustion activities); Transport (mobile combustion: road and rail and ship and aviation); Non-combustion (industrial process emissions and agriculture and waste); Industry (industrial combustion outside power and heat generation, including combustion for industrial manufacturing and fuel production); Power & heat (power and heat generation plants).

This content first appeared on, and is copyrighted to Carbon Brief.

About The Author

You may also like

Why Sustainability Isn’t Black or White — And Why It Matters for India

Indonesia’s Energy Transition Risks Overlooking Biodiversity Loss

Indonesia needs stronger ministerial coordination to unlock green job potential

The missing link: Why MSMEs need more than just budgetary support for green growth

Pricing Energy for Groundwater: A Path to Sustainable Irrigation and Climate Resilience

Great Content!!RauIAS also provides articles related to current affairs for UPSC and UPSC.