This installment of CarbonCopy’s series on India’s solar sector explores all the reasons why solar installations are slowing down despite readily available potential

In 2015, Prime Minister Narendra Modi upturned India’s renewable energy policy. Junking the National Solar Mission’s target of boosting India’s solar power capacity to 20 GW by 2022, he said his government would hit 100 GW instead.

Of this, 40 GW was to come from rooftop solar installations. The rest, from large- and medium-scale grid-connected solar projects. An avalanche of money was expected to flow into the sector. As Down To Earth reported at the time, officials at the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) expected “the total investment for upgrading to 100 GW solar power capacity (to) cost around ₹6,00,000 crore ($94 billion).”

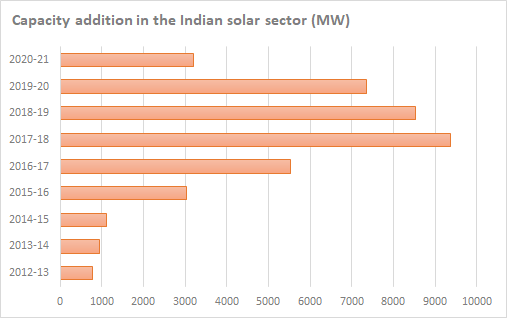

Close to six years later, India is nowhere near that target. By November 2020, the country’s installed solar capacity stood at 36.9 GW. Compounding matters, a clutch of marquee investors like SoftBank have exited, investment into the sector is falling, as is the rate at which India adds fresh solar capacity.

As the first part of this series said, industry players do not expect the sector to accelerate dramatically. The costs run deep. Today, solar power is cheaper than coal-based electricity. Its rising competitiveness is forcing thermal power plant companies to integrate vertically as the sector sees a shakeout. But if solar’s supply remains limited, India will continue to burn coal.

Despite a government push, why is solar slowing?

The backstory

The story of India’s solar sector is best narrated in three acts. In the first, our freshly independent democracy slowly created an indigenous solar sector to meet developmental imperatives such as rural electrification.

Solar was first discussed in India’s 3rd Five Year Plan (1961-66). It fell off planners’ radar during 1970-1980 – the 4th and 5th Plans focused on hydel, tidal and geothermal energy – but resurfaced in the Sixth Plan. In the years that followed, the country created both an indigenous solar manufacturing sector as well as developmental applications such as solar cookers, pumps and electrification.

In the second act, the sector lost its indigeneity and became a market for global actors. By the late 2000s, cheaper Chinese imports had pushed Indian manufacturers to the wall. By 2014, Indian developers met with the same fate. As foreign capital–firms such as SunEdison, Enel, Fortum, Aeon, SoftBank and Engie–entered the sector, Indian developers–EPC players such as GMR, GVK, Lanco and Emami–slipped into trouble.

Their cost of capital was higher. If local developers needed a 16% return, foreign investors were happy with a 12% return–and could consequently bid lower. “In this trade, technology is commoditised. What makes the difference is the cost of money,” said Santosh Khatelsal, the former managing director of Enerparc Energy. “No less than 65% of a bid is determined by the cost of money. Another 25% by capex. And just 5% by O&M.”

The first wave of foreign companies are now ceding ground to players with yet cheaper financing. This includes private funds (Macquarie, KKR, Actis and Blackstone), sovereign funds (ADIA), pension funds (CPPIB) and energy majors like Total trying to create a renewables portfolio. Only those Indian firms able to raise cheap money–like NTPC issuing bonds at 6.5%–are able to compete.

In all, riding on cheap imports, falling cost of money and aided by state programmes, India’s solar sector scored massive gains on competitiveness. The cost of setting up a solar park fell. “Ten years ago, it cost ₹10 crore to set up 1 MW. Now, you can set up a 1 MW plant [with far higher energy output] for ₹4-4.5 crore,” said a senior official at Renew Power. Given the firm’s forthcoming IPO, he did not want to be named. Tariffs crashed as well, falling from ₹18 in 2012 to below ₹2 now.

The third act is now underway. Even as global factors–falling cost of money and cost of modules–continue to drive solar tariffs down, domestic conditions are turning against the sector. One part of the reason? Solar is starting to disrupt the economics of India’s electricity infrastructure. Recent events in the rooftop sector illustrate that point.

What happened with rooftop solar?

Think of a factory or an office or a home. One with solar panels. It runs on the electricity generated from these and injects surplus electricity into the grid. If it needs more power than what its panels produce, it buys from the grid and pays only for that. That is rooftop solar.

Unlike countries like Germany, which pushed rooftop solar from the start, India started off on a small scale. Before 2015, India’s targets for this segment were distinctly unambitious, a former SECI official, who did not want to be identified, told CarbonCopy: “Just 10 MW a year.” That changed with Modi’s announcement. The country now had to hike its rooftop solar capacity to 40 GW by 2022.

The business proposition was clear enough. In any industry, raw material costs do not change all that much. Where companies can save is in the cost of converting that raw material into the finished product–a part of which is energy. For industrial units, however, power is costly.

In India, power costs rise with use. Surplus revenues from these are used to cross-subsidise less affluent segments. And so, firms began opting for rooftop projects.

By the end of 2020, five years after Modi’s target, rooftop solar installations had risen from 623 MW to 5.6 GW–well below the 40GW target, but a nine-fold increase all the same.

Then came the blowback.

In December 2020, India’s Ministry of Power restricted net metering only to rooftop units producing 10 kW or less. It wanted bigger units to follow ‘gross’ metering. Here, all power generated by the rooftop system goes to the grid. The enterprise is compensated at a fixed tariff. It has to source power as before from the grid at the usual tariff.

“The customers who go for rooftop solar are typically rich individuals and corporates,” said Rohit Vedhara of Aumenergy. “If a DISCOM’s most attractive customers go off the grid – or start supplying power instead of buying it – it will get harder for the DISCOM to maintain the grid.”

In the ensuing weeks and months, DISCOMs rushed to implement the order. Rooftop solar is still very small, agreed Vinay Rustagi, the managing director of Bridge To India, a Gurgaon-based advisory firm focusing on India’s renewables sector, but said DISCOMs do not want to lose any big customers. “It’s better [for them] to stop it now than another five years later.”

Gross metering, indeed, is fatal for rooftop solar. Take Punjab as an example.

| The economics of ‘net’ and ‘gross’ metering: The Punjab example Cost of power in Punjab: ₹7.2/KWh If a firm consumes 1 MW an hour and runs for 8 hours, daily cost of power: 8 x 1,000 x 7.2 = ₹57,600 If, with net metering, the firm imports no power from the grid, it pays nothing. The savings (effectively ₹57,600/day) go towards off-setting the investment in the rooftop system, which will pay for itself in five years. Assuming a 20% dependence on the grid, with net metering for the installed solar capacity, daily cost of power: 0.2 x 57,600= ₹11,520 Thus accumulating savings of ₹46,080/day. For gross metering, Punjab wants to pay no more than ₹1.75/unit for power bought from industrial units’ rooftop systems. A rooftop system producing 8MWh in a day will earn: 8 x 1,000 x 1.75 = ₹14,000/day. Its cost of power: 8 x 1,000 x 7.2 Kwh = ₹57,600. Its expenditure on power: ₹43,600/day |

“If some of the key industrial states were to shift to gross metering, then the payback period of a solar system would increase from the current 3 to 4 years to 5 to 6 years on average,” stated a report by IEEFA and JMK Research.

This is the first question. Why did India amp up its rooftop target without considering its implications for DISCOMs?

The costs run deep. “In Germany, 70% of all solar installations are rooftop,” said the former SECI official. “And what have we done? We have axed the sector.” The outcome is a dramatic reduction in the potential size of India’s solar market.

Without rooftop solar, ground-based solar projects have to drive growth in installed capacity. Complicating matters, growth is slowing there, too.

What ails ground solar

One set of factors bedevilling the sector is well known.

The first is DISCOMs, again. Their finances are a mess. The reasons extend beyond unchecked transmission and distribution losses. The government has declared solar as a must-run power. Which means other generators, like coal-based power plants, have to back down while solar is coming in.

The catch: DISCOMs have to pay thermal power producers like NTPC the fixed cost component of their PPA, regardless of whether they buy any power or not. NTPC’s Kudagi plant, said Raman Srikanth, dean of School of Natural Sciences & Engineering at Bangalore’s National Institute of Advanced Studies, makes Rs4,800 crore a year as just idling cost.

In other words, for every unit of solar power they buy, DISCOMs also pay fixed costs to the coal-based power plants they are backing down. That is the real cost of solar in this country.

Badly cash-strapped DISCOMs are not only baulking at fresh PPAs, they are also delaying payments to developers. “Payments are running as late as 8-9 months,” said Vinay Rustagi, the managing director of Bridge To India, a Gurgaon-based advisory firm focusing on India’s renewables sector.

The outcome is a squeeze. When payments come late, developers need more working capital. As players with cheaper finance come in, tariffs are coming down. At the same time, fixed costs have climbed due to higher land prices.

And yet, that is not the whole story. The cost of solar equipment is set to rise as well.

This is the second of a four-part series on India’s solar sector. Tomorrow: Why solar in India is set to get costlier

About The Author

You may also like

India’s wind and solar generation needs to grow five times by 2030 to align with 1.5°C: Report

Hope to raise $50 million for solar in next few months; focus on Africa: ISA chief

25% of Indian Railways could run on direct supply from solar panels: Study

One in Four Trains Could Run on Direct Supply from Solar Panels to Curb Emissions: Report

India’s solar sector bearing the costs of a poorly designed market